Magnetic North: Powering Canada’s Growth

Executive Summary

Canada’s relatively weak economic growth and currency in the 1990s led to persistent underperformance by Canadian equities. Even as foreign investors picked off bargains, Canadians seemed to lose faith in the ability of companies based here to deliver competitive returns. The result is that Canadian companies find themselves at a severe disadvantage in trying to grow in an era of global consolidation.

Canada has important strengths when it comes to attracting investment from Canadians and foreigners alike. But these advantages are overshadowed by powerful negatives, especially our high rates of corporate and personal income tax. Other countries have discovered in particular that cutting corporate taxes is a superb way to attract investment and boost the growth of jobs and incomes.

In addition to reducing taxes, Canada must continue to protect its interest in open trade and investment through transparent global rules. It must deal effectively with troubling new issues such as security and illegal immigration that threaten the future of its special relationship with its largest trading partner, the United States. And it must tackle a wide range of regulatory issues inhibiting trade and investment within Canada.

If we want the Canadian brand to be a magnet for investment by Canadians and foreigners alike, we have to look frankly at what matters to investors. We have to back up our words with consistent action. And then we have to convince the world that we really have changed our ways.

Sommaire

La croissance économique et la devise relativement faibles du Canada ont entraîné une contre-performance persistante des bourses canadiennes. Alors même que les investisseurs étrangers choisissent soigneusement les aubaines, les Canadiens semblent avoir perdu confiance en la capacité des entreprises établies ici de donner des rendements concurrentiels. Il s’ensuit que les sociétés canadiennes se trouvent gravement désavantagées dans leurs efforts de croissance en cette ère de mondialisation.

Le Canada possède d’importants atouts pour attirer les investissements des Canadiens comme des étrangers, mais ces avantages sont éclipsés par de puissants aspects négatifs, spécialement nos forts taux d’imposition. D’autres pays ont découvert en la réduction des taux d’imposition des entreprises un superbe moyen d’attirer les investissements et d’accélérer la croissance des emplois et des revenus.

En plus de réduire les impôts, le Canada doit continuer de protéger ses intérêts sur les plans du libéralisme commercial et de l’investissement par des règles mondiales transparentes. Il doit répondre efficacement à de nouvelles questions inquiétantes, comme la sécurité et l’immigration, qui menacent la relation spéciale qu’il entretient avec son principal partenaire commercial, les États-Unis. Il doit en outre s’attaquer à un vaste éventail de problèmes réglementaires qui entravent le commerce et l’investissement au Canada.

Si nous voulons que l’étiquette Canada continue d’attirer les investissements tant canadiens qu’étrangers, nous devons considérer franchement ce qui compte pour les investisseurs, appuyer la parole par le geste, puis convaincre le monde que nous avons changé notre façon d’agir.

Discounting Canada’s Future

Future prosperity flows from investment today. That is as unalterably true for countries as it is for families. Yet many Canadians remain suspicious of foreign investment even as they hustle to get their own money out.

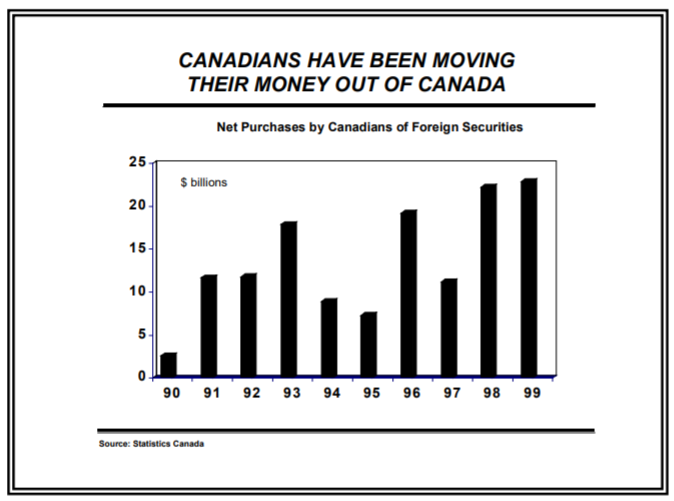

In 1999, amidst a global frenzy of mergers, acquisitions and consolidations, a heavily discounted Canadian dollar and a host of undervalued assets finally prompted a wave of foreign takeovers of Canadian companies. At the same time, however, Canadian investors put a net $23 billion into foreign securities. Since 1990, Canadians have shipped more than $135 billion out of their own country.

Capital flight on this scale is a problem more familiar to distressed developing economies, but the impact on the Canadian dollar and on the value of Canadian enterprises is the same. The Toronto Stock Exchange 300 Index underperformed American indexes by huge margins throughout the 1990s. And Canadians have been saying with their own savings that they have lost faith in the ability of companies operating in this country to deliver competitive returns.

A small open economy such as Canada needs a healthy two-way flow of investment. It must compete to attract the investment of foreign companies for operations that will serve the North American or global markets. At the same time, it must encourage Canadian-based companies to set their sights high and expand into the rest of the world.

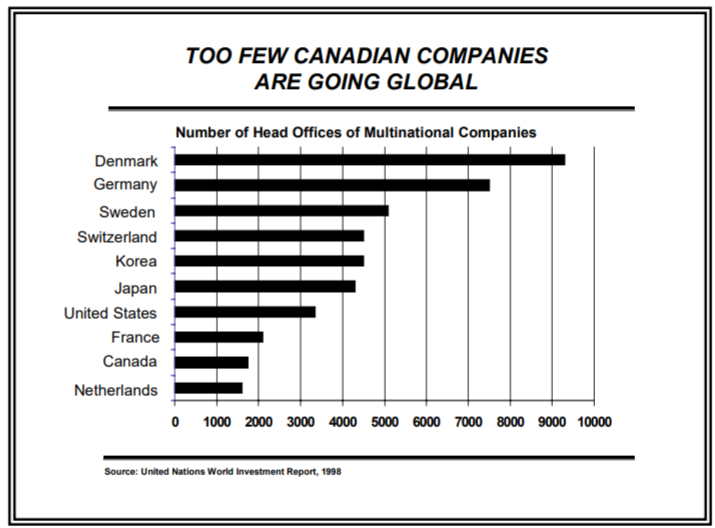

Dezso Horvath, Dean of the Schulich School of Business at York University, has noted that Canada both is losing ground in its ability to attract foreign investment and has a poor record of fostering Canadian-based transnational companies. As a host for foreign direct investment, Canada by 1997 had fallen behind Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands. And while Canada’s outflows of FDI have continued to grow, it remains the home base for remarkably few transnational companies. Denmark is now home to about five times as many transnational corporations as Canada. Other countries including South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland and even Finland also outstrip Canada’s total. As of early 2000, only two of the top 150 global corporations by market capitalization were based in Canada. While almost half had head offices in the United States, six were based in the Netherlands and five in Switzerland. The combination of lagging investment inflows and a weak global presence undermines both the performance of Canadian enterprises and the way they are perceived by investors worldwide.

“There exists in Canada what I would call a Canada discount factor,” said Anthony Fell, Chairman of the Board of RBC Dominion Securities Inc. “If you look at equity markets here, at a company in Canada and an identical company in the United States, the American company would probably trade at a price-to-earnings multiple of three points higher than the Canadian one.”

A dollar of earnings in the hands of a Canadian company, in other words, is persistently worth less than the same dollar of earnings in the hands of American competitors. In an era of rampant global consolidation, this underperformance of Canadian stocks does more than simply reduce the value of investments supporting the dreams and pensions of Canadians. It also hurts the ability of Canadian companies to grow – either internally or through acquisition abroad.

“The combination of the low value of the dollar plus the low price- to-earnings multiples in the market makes it very difficult for Canadian companies to invest in growth,” said John Mayberry, President and Chief Executive Officer of Dofasco Inc. “Investments that would have been affordable become bet-the-farm investments. Because Canadians tend to be a conservative lot by nature, those investments are often not made. Everyone becomes a sitting duck.”

While the weak dollar and low multiples do leave Canadian companies vulnerable to takeovers, the problems facing the country have little to do with the passports of shareholders. Canadian companies and foreign-owned transnationals are facing the same pressures and following many of the same strategies for the same reasons. The issue is whether Canada can convince foreign and domestic investors alike that our country is the best possible home base for a business that has to serve a continental or global market.

Despite Canada’s many attractions, global investors remain wary. Canada has a long history of heavy-handed government intervention and restrictions on foreign investment. “In Canada, we should worry less about the nationality of capital and worry more about the behaviour of capital,” said David Culver, Chairman of CAI Capital Corporation and a former chief executive of Alcan Aluminium Limited. “I say that our country is better off with a good foreign investment that is well run than we are with a Canadian investment that is poorly run.”

If Canada does want to attract and retain critical corporate functions and influence, and to create more and better jobs for Canadians, it has a long way to go. And even if the country does address the key issues discouraging investment today, Canadians in both the public and private sectors will have to work hard to convince investors that the country really has changed its ways.

“There is a kind of over-relaxed attitude, one that is encouraged by the government’s fiscal policies,” said Howard Mann, President and Chief

Executive Officer of McCain Foods Limited, a man who came to Canada several years ago after a distinguished career in Britain. “People here tend to stand on the moving staircases. Canada has an Escalator Economy. Stand on it and be carried to the top. Don’t work for it. Don’t run up it. If Canada wants to compete with the United States and the rest of the world, the government has to help people to run, by making them accountable for their own demand for public spending.”

A Solid Foundation for Growth

Canada already has come a long way from the dark days of the early 1990s. While the adjustment period was difficult, Canadian companies moved quickly to grasp the opportunities created by an increasingly integrated North American economy. Total trade between Canada and the United States has increased by 160 percent since 1988. It now exceeds $1.5 billion a day or $1.1 million a minute. Canada’s merchandise trade surplus with the United States reached more than $60 billion in 1999.

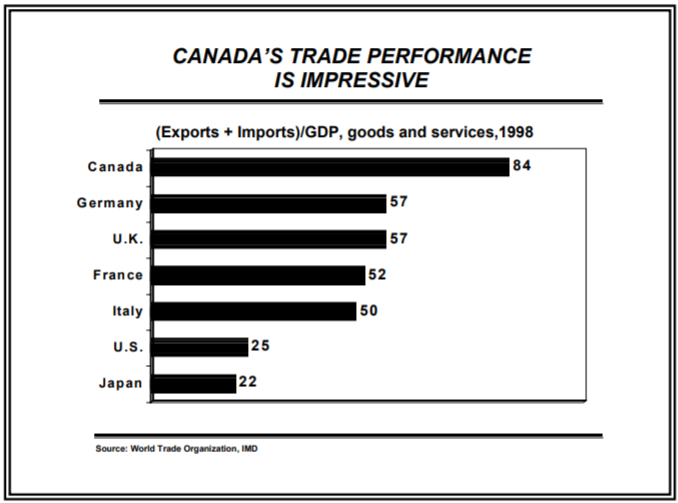

Canada’s trade with other countries also has increased. As a result, trade in goods and services as a percentage of GDP grew from 42 percent in 1971 to 84 percent by 1998. Canada’s trade as a share of its economy is more than 25 percentage points higher than that of both the United Kingdom and Germany more than triple that of the United States. And while commodities remain an important part of Canada’s export mix, the proportion of value-added exports has been rising steadily. Exports of machinery and automobiles rose from 28 percent of the total in 1980 to 45 percent by 1998.

This dynamic performance on the trade front has driven an acceleration of economic growth. After a lacklustre performance in the first half of the decade, Canada’s growth rate surged to 4 percent in 1997, 3.1 percent in 1998 and 4.2 percent in 1999. While continental economic integration has helped Canada benefit from the prolonged expansion in the United States, Canada last year actually led the G-7 in economic growth, surpassing even the American juggernaut.

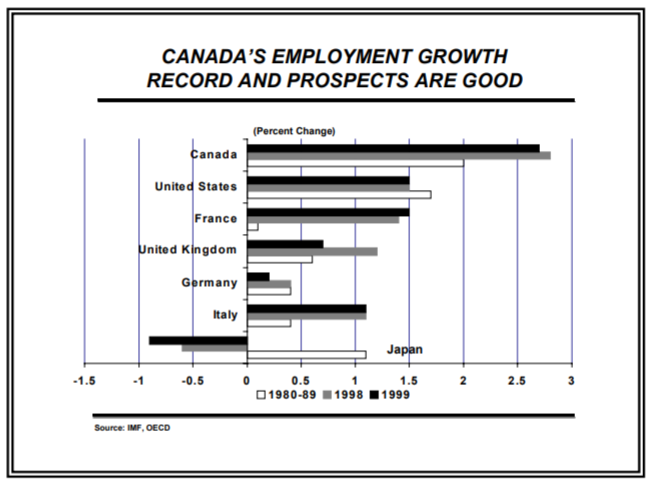

Canada also is leading the G-7 in job growth. The country posted employment growth of 2.7 percent in 1999, and is expected to lead the G-7 again this year. The economy created 427,000 jobs last year, pushing the unemployment rate to its lowest level in almost a quarter century. The country’s output gap is now almost zero, and although both inflation and interest rates are inching up from their historic lows, the unemployment rate should continue its downward track.

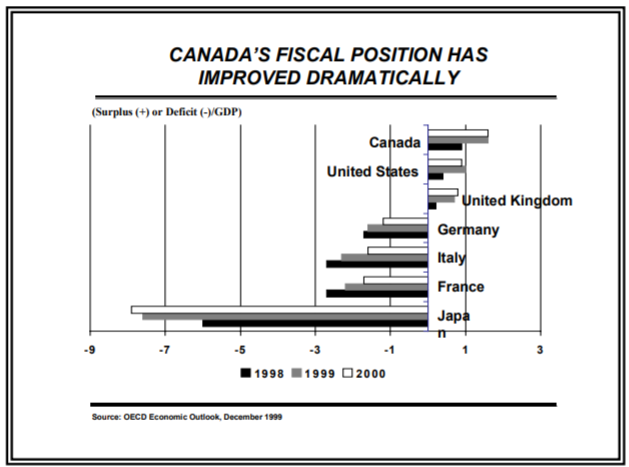

Economic expansion has fuelled fiscal health as well. The national balance sheet has generated three consecutive years of fiscal surpluses, with a fourth expected this year. Canada has the strongest surplus-to-GDP ratio in the G-7, and the federal government alone is now expecting a cumulative surplus over the next five years of more than $100 billion. The stream of surpluses has in turn spurred the beginnings of what could be a steady stream of cuts in tax rates.

Public debt levels remain amongst the highest in the industrialized world, but the combination of strong economic growth and repeated budget surpluses is rapidly pushing Canada’s indebtedness down in relation to the size of its economy. On a national accounts basis, Canada’s net debt to GDP ratio is expected to fall to 54 percent this year from 69 percent in 1996, a drop of 15 percentage points in just four years.

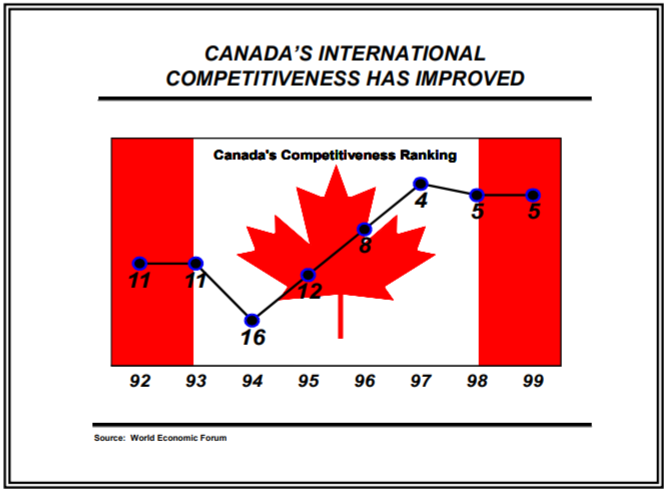

By the end of the decade, Canada’s progress was being widely recognized. The country has placed in the top five in the World Economic Forum’s annual ranking of the most competitive economies for three years in a row. It has been ranked number one for quality of life according to the United Nations Human Development Index for six years in a row. And both KPMG and the Economist Intelligence Unit say Canada offers the lowest cost of doing business in the G-7.

Canada also has a solid foundation for the information-based economy of the future. Relatively more Canadians use the Internet than Americans, and do so for longer periods. That is partly because Canada is at the forefront of developing the infrastructure of the Internet, and also because Canada has the lowest costs in the G-7 for Internet access.

In addition to being one of the most wired nations in the world, Canada has one of the best-educated populations. It is amongst the highest spenders on public education, but more importantly has the highest proportion of post-secondary graduates in its working-age population. Canada indeed would appear to be perfectly positioned for success in the years ahead.

Falling Behind the Global Pace of Change

Canada’s major problem has less to do with the direction we are going than the slow speed with which we are making progress. Driven by the relentless advance of information and communications technology, global flows of information are leaping by orders of magnitude. This abrupt abundance of information is in turn transforming the way business gets done around the world.

The growth of national economies, productivity and employment depends increasingly on industries and services that barely existed ten years ago. More and more people are employed in occupations that have only come into existence in the past decade. Constantly evolving technology has accelerated the process of “creative destruction” in every industry, and given new importance to the process of shifting capital from mature or declining technologies into new activities on the cutting edge.

New business models are transforming the boundaries of the firm. “Pioneers of the 20th century corporation – people like Henry Ford, Frederick Taylor, Alfred Sloan, William Hearst and Thomas Watson –

had no idea what would become of it, nor how it would change the world,” said Don Tapscott, Chairman of e-business consulting firm Digital 4Sight. “How could they have known that this institution, rooted in hierarchy, command-control cultures and ’scientific management’ would turn into its opposite – a place where success depends on letting go, on teamwork, and trusting the wisdom of front-line employees. We are again in the early days of a new corporate form.”

The traditional corporate structure is being supplanted by new models such as business webs, agoras, aggregations, value chains and distributive networks. “The Internet is becoming the infrastructure for all business activity: the foundation of a new economy, transforming all sectors in the process,” Mr. Tapscott added.

Many Canadians as individuals have launched themselves into this new era, but public policy is still geared to the past. Vast numbers of public sector employees and huge sums of money continue to be poured into vain attempts to maintain the status quo. Government programs prop up companies that can no longer compete, subsidize jobs in traditional industries and encourage people not to move, not to acquire more marketable skills, not to shake off persistent dependence on the public purse.

As a result, Canada seems stuck in limbo, caught between its pride in past achievements and the need for revolutionary change in order to achieve its aspirations for the future. This reluctance to change is having a significant impact on the country’s ability to attract new business investment – whether from Canadian companies or foreigners.

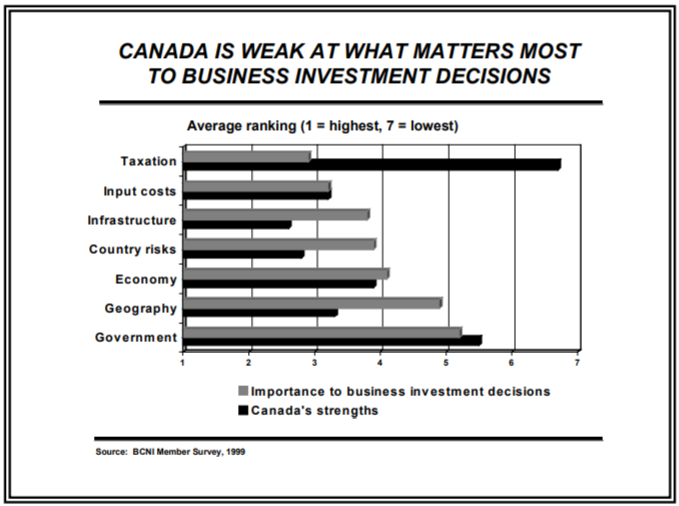

The work of the Canada Global Leadership Initiative included a 1999 survey of the member chief executive officers of the BCNI. It sought their views on what really matters to corporate investment decisions – and on Canada’s

relative strengths and weaknesses. What it found was that Canada tends to rate poorly on the factors that now matter the most when a company is deciding where to expand its activities.

Overall, a company considering where to locate a new investment looks first at the rate of taxation, followed by the cost and availability of critical inputs and then the quality of infrastructure and country risk factors. Infrastructure is seen as Canada’s greatest competitive advantage, and we are a low-risk place to do business with the geographic advantage of being next-door to the American market. But the size and role of government and especially the resulting burden of taxation stand out as major problem areas.

When the broad categories were broken down more specifically, the importance of Canada’s failings on the tax front became even more evident. Among the survey findings:

- Macroeconomic environment. Canada is open to trade, has low inflation and interest rates and plenty of people ready and willing to work, all important advantages. But its tax burden and its growth prospects rate poorly – and those are the primary considerations for business investment.

- Role of government. Canada wins praise for its generosity in handing out subsidies and incentives, but Canada’s CEOs made it clear that this is the least important influence on international decisions on where to invest.

The most important consideration is the level of taxation a government charges for its services, and on this score, Canada is failing abysmally. Subsequent interviews with chief executives in multinational corporations confirmed that while subsidies may tilt the balance between the finalists for location of a new operation, sites in high-tax countries do not even make the short list. - Level and structure of taxation. Reinforcing this point is the fact that Canada is most competitive when it comes to sales and consumption taxes – the kind of taxation that has the least impact on business investment. Corporate and personal income taxes are the ones that matter – and Canada’s are among the highest in the industrialized world.

- Cost and availability of inputs. Canada has plenty of cheap land and resources, but investments in new operations today depend primarily on the supply of capital and of highly skilled labour. Once again, these are considered areas of relative weakness for Canada.

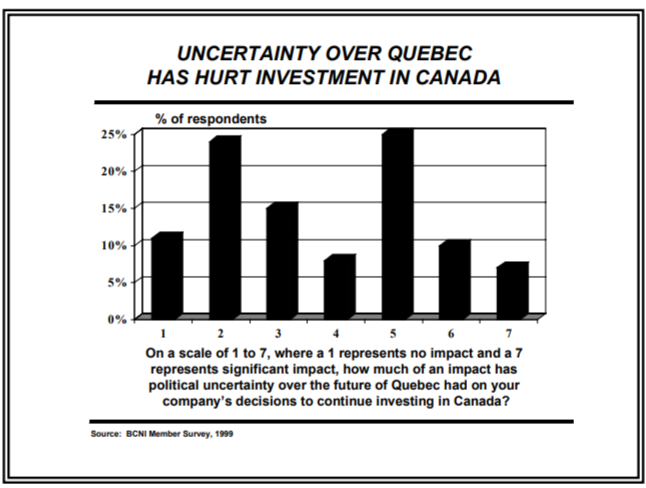

- Country risks. Canada is considered a safe place overall, but long-term political stability is a source of concern, as is the strength and stability of our currency – the two most important factors for investment decisions. Some insight into the first weakness could be seen in the responses to a separate question on the impact of political uncertainty over the future of Quebec. More than half of respondents (52 percent) said this has had at least a moderate impact (four or more on a scale of one to seven) on their companies’ decisions to continue investing in Canada. Almost half, 44 percent, rated the impact at 5 or higher.

- Infrastructure. Canada’s communications, education, social and legal infrastructures are all considered important sources of competitive advantage. A shortfall in transportation infrastructure was seen as the country’s most important failing.

As has been noted already, Canada does have important strengths, especially in the areas of education and social infrastructure, openness to trade and proximity to a large market. Any strategy for enhancing Canada’s ability to attract more investment in high-value activities must build on these strengths.

At the same time, it is critical to deal decisively with the greatest barriers to progress. There is a clear perception that Canada is relying too heavily on old-economy strengths such as cheap land and plentiful natural resources. Despite our solid education infrastructure, there are warning lights about the future supply of highly skilled people. The supply and cost of capital, as demonstrated by the underperformance of Canadian equities, is clearly a serious problem.

Canada’s level and structure of taxation, however, especially on corporate and personal income taxes, stand out as the single most urgent issue. Whatever else the country does, Canada must address its shortcomings on the tax front if it is to attract the investment it will need to power its growth in the years ahead.

The Power of Corporate Taxation

Canada not only imposes some of the highest corporate income tax rates in the industrialized world, but maintains a very complex system that provides some sectors with more competitive effective tax rates than others. Canadian corporate taxes are especially onerous for the service sector, which is the very area in which we expect most new jobs to be created.

“Canada’s tax rates are impacting the country,” said John Wetmore, President and Chief Executive Officer, IBM Canada Ltd. “Many participants in our industry are locating and growing in low-tax jurisdictions, and Canada is not as attractive in terms of its tax rates.”

“Canada is undoubtedly one of the high tax regimes that we’re in,” said John Willson, former chief executive officer of Placer Dome Inc. “The United States is much more attractive. So is Chile. So is Australia, not to mention Papua New Guinea. We spend a great deal of time and energy trying to make sure that we produce money in a jurisdiction where we can find some shelter from heavy tax burdens.”

“Forget about our rates, our tax structure is anti-development,” suggested Israel Asper, Executive Chairman of the Board of CanWest Global Communications Corp. “At best, it reflects a lack of understanding among politicians and officials about how the real world of commerce works. At worst, it betrays a destructive anti-business bias.”

Earlier this decade, the federal government commissioned a Technical Committee on Business Taxation. Its report in 1998 highlighted the structural problems of business taxation and issued detailed recommendations for resolving them. However, it was crippled by a mandate that insisted on revenue neutrality. From being a country where some industries faced competitive burdens and others highly uncompetitive ones, this approach would have created as many losers as winners and made every sector equally uncompetitive.

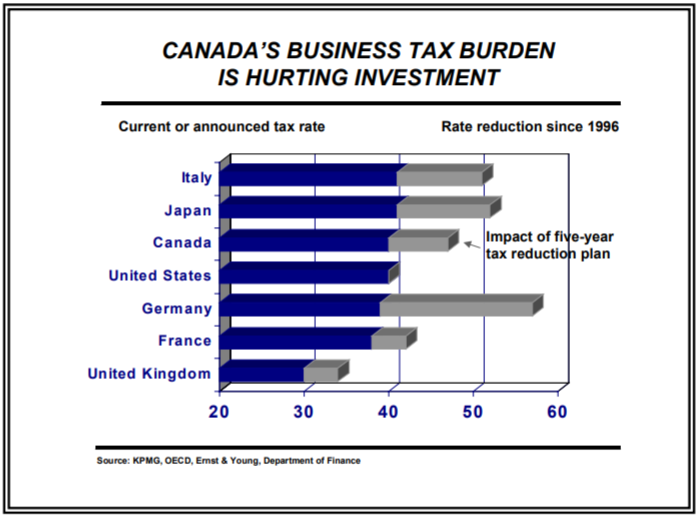

Jack Mintz, who chaired that committee, is now President and Chief Executive Officer of the C.D. Howe Institute. In 1999, he took a look at how the world had changed even in the short time since the committee report was published and shelved by the government. He found that in just three years, Canada had gone from being middle of the road in its corporate tax rates to the second highest in the G-7.

Germany, France, Sweden, Spain, Ireland, Australia and Japan: the list of countries cutting corporate taxes keeps growing. Governments of the left and right alike have realized that a competitive corporate tax structure is the single most effective way to attract new investment in leading-edge industries.

Professor Mintz concluded that the speed and extent of corporate tax reductions in other countries combined with the growing mobility of capital in the global economy pose a serious threat to Canada’s future growth. Canada’s high business tax burden reduces its competitiveness even after factoring in the benefits of its public services and infrastructure.

“Canada cannot wait several years to review business taxation. Although it is important – and politically popular – to reduce personal taxes, it is the business tax system that creates the greatest leverage in improving productivity and growth of incomes in Canada, as other countries such as Ireland have found out.”

In the 1980s, Ireland had an unemployment rate that reached 18 percent, had a national debt equal to 125 percent of GDP and was seeing people leave the country at the rate of 1,000 a week. Since dramatically slashing corporate tax rates early this decade, it has enjoyed the fastest economic growth in the industrialized world over the past decade. Irish designed computer software grew from a $30 million industry to more than $1 billion in the 1990s. Technology-based employers now account for about 10 percent of its workforce and 20 percent of Ireland’s GDP.

The key lesson from Ireland’s experiment in corporate tax-cutting is this: despite the fact that its average corporate tax rate is less than one third of Canada’s, Ireland collects more money from this source as a percentage of GDP than Canada does. Corporate tax cuts would have a clear impact on investment, productivity and economic growth, and can be delivered at very low cost to governments even in the short term.

Professor Mintz recommended a three-pronged approach: cutting Canada’s corporate income tax rates below those in the United States; improving the neutrality and simplicity of the business tax system, which would have the greatest impact on the service sector, where most new jobs are being created; and reducing Canada’s reliance on inefficient profit-insensitive taxes that have little relationship to the costs of public services provided to business.

Professor Richard Harris of Simon Fraser University noted in work for the BCNI that foreign direct investment is increasingly sensitive to differences in corporate tax rates. For instance, a 1998 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research by Rosanne Altshuler, Harry Grubert and T. Scott Newton examined investment decisions by American manufacturing affiliates in 58 countries. They concluded that a 10 percent increase in corporate taxes in 1984 would have led to a 15 percent drop in foreign investment – and that figure doubled to a 30 percent loss by 1992. The implication is that both the negative impact of uncompetitive corporate taxes and the potential gains from a tax cut doubled in just eight years. And given the extent of global economic integration since 1992, the impact is likely to be even more significant today.

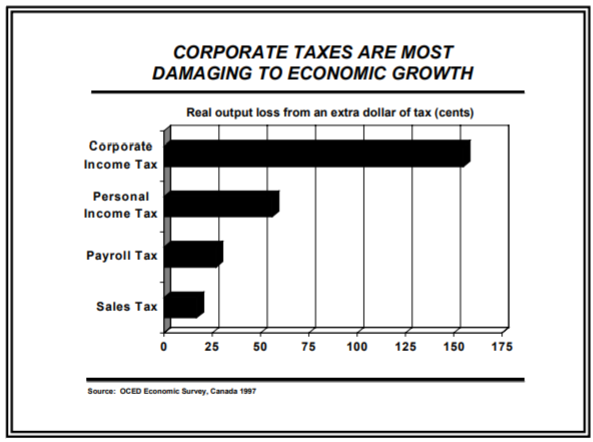

Professor Harris also confirmed that not all taxes are equal in terms of their impact on the economy. All taxes distort activity and reduce output to some extent. But based on figures provided to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development by Canada’s Department of Finance, an extra dollar in sales tax causes a loss in real economic output of just 17 cents. A dollar of payroll tax costs the economy 27 cents, while a dollar in personal income tax reduces output by 56 cents. But an extra dollar in corporate income tax has the effect of cutting real economic output by $1.55. If the objective is to stimulate economic growth, cutting corporate taxes is the most effective strategy.

Finally, he pointed out that in a knowledge-based global economy, skilled labour and physical capital (such as new machinery and equipment) are complementary inputs. A country with more people who have higher skill levels will both see greater productivity growth and attract more capital investment. And a country that attracts more investment in productivity-enhancing technologies is one that provides more work opportunities for highly skilled people.

This has important implications for the tax system. Lower corporate taxes will improve the odds for investment in the leading-edge technology that creates more high-skill opportunities. Personal income tax rates affect individual decisions about whether to invest time and money in more education, which in turn affect another important factor in investment decisions, the supply of highly skilled people. “Consequently, a cut in income taxes which raises the return to human capital acquisition may raise the growth rate both by encouraging more human capital formation and by attracting an inflow of new investment. Both of these are growth enhancing,” Professor Harris concluded.

This year’s federal budget made some moves in the right direction, but our competitors are moving much faster. If Canada does not accelerate its plans, it will miss an important opportunity to gain a real competitive advantage an attracting investment.

Staying Open for Business

Taxation may be the most critical barrier to greater business investment in Canada, but others must be addressed both at home and abroad. Internationally, Canada must continue to push for freer flows of trade and investment combined with more effective and transparent global rules. Domestically, it must deal with a broad range of irritants at both the federal and provincial levels.

Global competition is healthy for Canada not just because consumers win, but because Canadian enterprises can and do win as well. Canadians can compete effectively in an open global economy, and it is in all of our interests to ensure the continued evolution of a transparent and effective system of international rules that encourage the free flow of goods, services and investment. Canada should therefore continue to work hard to encourage negotiations within the World Trade Organization as well as regional fora that can contribute to further trade and investment liberalization.

There is, however, mounting public concern about the speed and impact of globalization in many countries, and these worries have contributed to sluggish progress at the multilateral level. Canada therefore should continue to look for opportunities at the bilateral level as well.

Japan, for instance, which has no bilateral trade agreements, is now showing increasing interest. During last year’s Team Canada mission to Japan, the Canadian and Japanese prime ministers asked their respective business communities to explore the potential for freer trade between the two countries. The Business Council on National Issues and its Japanese counterpart, the Keidanren, presented initial reports to the annual meeting of the Canada Japan Business Committee in May, 2000, and agreed to continue their work in the year ahead.

Such initiatives are important to help maintain a global focus to Canada’s trade and investment strategy. But given the high and still growing degree of integration between the Canadian and American economies, we cannot ignore the evolution of the political and economic environment in the United States. Rising American concern over issues such as security, illegal immigration and illicit drugs will require Canada to decide how it wants to be seen and treated by Americans and their political leaders. If Canada is not seen as part of the solution to their concerns, we will be treated as part of the problem.

Professor Michael Hart of Carleton University has suggested that the time has come for a serious look at tearing down the remaining barriers to the free movement of people as well as goods and services across the border with the United States. “American advantages ranging from tax levels to research policies act as a powerful magnet. The challenge for Canadians has always been to adopt policies that offset to some extent the natural attraction of the United States as an investment location. Canada is failing to meet this challenge. Trade policy alone cannot offset this failure, but trade negotiations can play an important part in reversing the trend.”

While a comprehensive negotiation may prove difficult to sell politically on either side of the border, he said completing the work begun in the 1980s and achieving a seamless market would help Canada and the United States achieve their shared interest in a well-functioning North American economy. “For both, reducing the impact of the border may prove the best way to preserve Canada’s status as an independent, reliable and vibrant partner of the United States in the pursuit of common trade, economic and security interests.”

The current approach of gradually eliminating irritants that delay passage at the border is useful, but the incremental approach may not be enough. Canada will have to decide what it will take to maintain privileged access to the United States market, and whether that access is worth the price that may be demanded. In any case, a comprehensive approach is more likely to fire imaginations and lead to substantial improvements.

“Do we really need a plethora of protections to be Canadians?” asked Jean Monty, President and Chief Executive Officer of BCE Inc. “I don’t think we have enough faith in ourselves. The Americans are going to walk all over us if we don’t deal with them from a position of economic strength.”

“One of the things we’ve got to come to grips with as a country is that we actually can compete with Americans,” said Sanford Riley,

President and Chief Executive Officer, Investors Group Inc. “For too long, we have been saddled with an inferiority complex. In some ways, we are our own worst enemies. If Canadians had more confidence in their ability to compete, they would be able to compete more effectively. Part of the problem with the border is that it is a psychological issue. Some people feel that you have to be on the other side of the border to be successful.”

Strong and effective political institutions and governance are critical to economic leadership. While the Canadian federation is one of the most effective and enduring in the world, it is under increasing stress and fissures are widening between levels of government.

In particular, despite the Agreement on Internal Trade, internal barriers to the movement of people, goods and services persist, and governments have given their removal a low priority. Restricting people’s ability to live and work where they please discourages movement and reinforces regions of high unemployment and dependency. Policies supposedly intended to protect jobs and opportunity for residents of each province instead fragment the Canadian marketplace and leave Canadian enterprises smaller and less competitive.

“We have the disunited provinces of Canada,” said James Shepard, former chief executive officer of Finning International Inc. “The most unfree trade area in the western hemisphere is within Canada, province to province. We have freer trade with Washington than we do with Alberta. That’s another dimension that works against us.”

“It is bad enough that we have a small economy relative to the United States. But then we slice it about ten different ways and make ourselves smaller and smaller,” added David O’Brien, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of Canadian Pacific Limited.

Seymour Schulich, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of FrancoNevada Mining Corporation Limited, has suggested that provincial efforts to keep jobs and economic activity within their own boundaries end up hurting both the economy and the reputation of the entire country.

He cites the behaviour of Newfoundland and Labrador as the most recent example. The provincial government first promised a ten-year tax holiday for businesses creating new ventures in the province – and then withdrew the legislation after the discovery of the Voisey’s Bay nickel deposit. Since then, the province has refused to allow development of Voisey’s Bay without a guarantee that all ores will be smelted within the province rather than elsewhere in Canada. “Capital today flows like water to places where it’s wanted, welcome and able to earn a fair return for its providers,” Mr. Schulich said.

Inter-provincial jealousies are compounded by Canada’s approach to regional development. Subsidies to individuals and businesses alike are geared to maintaining existing patterns of employment rather than encouraging change. Decades of grants, loans and other transfers have failed to make any significant and enduring progress in reducing unemployment rates and raising incomes in Canada’s worst-off regions. Instead, for provinces and for individual Canadians, we have seen a reinforcement of dependence.

While policy differences between provinces can cause problems in themselves, the overall pattern of regulation across the country also can send negative signals to domestic and foreign investors alike. In environmental policy, for instance, the United States often has tougher rules, but they are more transparent and consistently enforced.

“In the United States, you fill in an application. The rules are known. They check to see whether your proposal meets the rules, and what you have to change to make it fit. They give you your permit. And then when you start up, they come back and check. If you have not complied with the rules, they shut you down,” said Roger Phillips, President and Chief Executive Officer of IPSCO Inc. The problem in Canada is not stricter environmental standards, but a review process that tends to be long, uncertain and inconsistent. “In Canada, if we want to make a 30 percent increase in our steel works capacity, we will go through an environmental process that will last a minimum of 24 months and more likely 36 months.”

Labour regulations, entrenched work rules and a reputation for labour strife also can discourage investors. “We have so many rigidities still in our system that it is scary,” said David O’Brien of Canadian Pacific. “To take just one example, at our last set of negotiations with the union representing employees at one of our hotel properties, they came forward with a shopping list of demands. Their opening position was that they didn’t want to work weekends or nights. This is in a hotel. It’s preposterous. You can’t run a hotel and not be open at night. But there is an attitude, not always in the rank and file, sometimes just in the leadership, that you face in many places in Canada.”

These are just isolated examples of a pattern of policies and attitudes that continues to damage Canada’s reputation as a place to invest –

and in a world of rapid change, reputation matters more than ever. Whatever policies governments choose, they must send clear signals and follow through. “If you are going to have a policy, it’s got to be consistent with time. You can’t yo-yo this thing,” said David Caplan, Chairman, Pratt & Whitney Canada Inc. “There is no way we can plan our future and win future global mandates without knowing what the rules of the game are going to be.”

Magnetic North: Strengthening Canada’s Brand

In conclusion, Canada does have strengths, and we must build on them. We have established ourselves as an economy with low inflation reinforced by governments that are running fiscal surpluses. We have excellent access to major markets and a strong record of success in global trade. We have a world-class resource sector, productive manufacturers and a critical mass of key technologies for the new economy. We are one of the most wired nations in the world, backed up by a well-educated population and a highly developed social infrastructure. It is this combination that has allowed Canada to be ranked simultaneously as one of the most competitive economies in the world and as the country with the highest quality of life.

Canadians in both the private and public sectors must not be shy about these strengths. Just as business and government leaders have used the Team Canada concept to enhance trade performance, we need to work together to build Canada’s profile and win greater recognition of our country’s potential as the preferred location for investment in global enterprises. We have to be proud of what we have achieved together and tell the world about our confidence in Canada’s future.

At the same time, however, we must address our weaknesses. We have to bring down our sky-high mountain of public debt. We have to reinforce confidence in the stability and ultimate strength of the Canadian dollar. We have to boost our lagging pace of investment in research and development. We have to become far more effective at turning new ideas into innovative businesses. And we have to bring down the excessive tax burden that is undermining our competitiveness, endangering our base of human capital and discouraging Canadians and foreigners alike from seeing this country as a viable location for successful global enterprises.

Canada can make itself the best place in the world to invest and build successful global businesses. We can create confidence and attract the capital that will ensure the sustainable creation of more and better jobs for Canadians. But we must begin by looking honestly at what matters to investors in a rapidly evolving global economy. We must deal with our shortcomings through consistent action that encourages people to take risks and succeed instead of maintaining policies that subsidize stagnation. Finally, we must work together to convince the rest of the world that we really have changed our ways.

If we want Canada to be a compelling magnet for the investment that will power tomorrow’s growth, we must show that our country can be a leader in the world and that we want to be home to global leaders.