Compete to win: the Wilson panel report six years later

Executive Summary

In 2007, in response to a growing national debate over whether Canada’s economic base was being “hollowed out” by foreign takeovers, the federal government established the Competition Policy Review Panel, led by respected business executive L.R. (Red) Wilson.

The panel’s mandate was to review Canadian competition and foreign investment policies with the goal of making Canada more competitive in an increasingly global marketplace.

In 2008, the panel released a wide-ranging report titled “Compete to Win”. The first 17 of its recommendations focused on foreign investment review and competition policy. The remainder of the panel’s 65 recommendations covered a range of topics affecting competitiveness including taxation, skills and immigration, cities, support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), trade, intellectual property and copyright, and the establishment of a Canadian Competition Council.

Assessing the government’s progress in implementing the panel’s recommendations, I find mixed results. The government deserves high marks for its reforms of the Competition Act, its business-friendly tax regime, its efforts to expand and facilitate trade, and reforms in the area of immigration and intellectual property and copyright.

However, little progress has been made in three key areas. The investment review process has become more uncertain and actively discourages investment by stateowned enterprises (SOEs), a growing source of global capital. The government has more work to do to loosen foreign investment restrictions in two key sectors: telecom and air transportation. Finally, the government missed an important opportunity to keep an ongoing focus on competiveness by declining to establish the Canadian Competition Council.

The underlying pressures facing Canada as it competes in the global economy have not abated. More than ever, we need all the advantages that a competitiveness-focused policy regime can give. The unfinished business from the Wilson panel should be a renewed priority for a country that seeks to “compete to win”.

Introduction

The spring of 2007 saw Canada in the midst of a vigorous national debate over whether its corporate sector was being “hollowed out” by foreign takeovers. The trigger was the sale of Canadian corporate icons such as Alcan, Dofasco and Inco to global firms headquartered outside the country. Harkening back to the Walter Gordon era of economic nationalism in the late 1950s, Canadians were asking themselves whether Canada was destined to become a “branch plant” economy, largely controlled by foreign interests.

In response, the federal government led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper established the Competition Policy Review Panel. The blue-ribbon panel was chaired by senior business leader L.R. (Red) Wilson and included respected business figures Murray Edwards, Isabelle Hudon, Tom Jenkins and Brian Levitt. The members of the panel provided a wide regional and sectoral representation of corporate Canada. Their mandate was to conduct research and hold consultations to review Canadian competition and foreign investment policies with the goal of making Canada more competitive in an increasingly global marketplace.

The panel began its work with a discussion paper, “Sharpening Canada’s Competitive Edge,” released in October 2007. The call for submissions from interested parties resulted in 155 briefs from business, the legal community, governments, academics, unions and civil society. The panel reviewed best practices in OECD countries and commissioned more than 20 research reports on relevant policy issues. Finally, the panel met with more than 150 individuals and groups in 13 sessions across the country.

The panel exhorted Canadians to ‘skate harder, shoot harder and keep our elbows up in the corners’

The panel titled its final report to the Minister of Industry “Compete to Win,” and used familiar hockey analogies to illustrate its overarching point: “…[R]aising Canada’s overall economic performance through greater competition will provide Canadians with a higher standard of living.” The panel exhorted Canadians to “skate harder, shoot harder and keep our elbows up in the corners”. The report detailed 65 specific recommendations to improve Canada’s economic performance.

In this paper, I review the findings and recommendations of the Wilson panel to assess the progress the federal government has made in implementing them. In the next section, I examine the findings of the panel that underpinned its recommendations. The following two sections consider the recommendations and the state of their implementation. Finally, I provide an overall assessment of the federal government’s efforts to reform competition and foreign investment policies, along with some conclusions and thoughts regarding future reforms needed to ensure that Canada can “compete to win”.

What the Wilson Panel Found

The panel’s report provides a fascinating snapshot of the state of Canadian competitiveness in 2008, just before the financial crisis in the United States and the advent of a deep and prolonged recession. Many of the same forces remain at work today although they were, for a time, overshadowed by effects of the recession. The panel noted the ongoing effects of globalization and the increasing pace of technical change that were eroding the manufacturing advantages that countries such as Canada traditionally enjoyed.

While Canada’s major trade agreements such as the NAFTA served it well, the country was ill-prepared to go toe-to-toe with emerging-market competitors

As large emerging-market economies began to assert their place in the world economy and commerce became increasingly global rather than regional, the skills and capital-stock advantages of Canada diminished. While emerging economies brought increased demand for Canada’s natural resources and agricultural goods, they also brought skilled workers with relatively low wages and vast economies of scale. Concomitantly, firms began to develop global value chains to produce products and services, and looked increasingly outside of North America and Europe to source the inputs and skills they needed. While Canada’s major trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) served it well, the country was ill-prepared to go toe-to-toe with emerging-market competitors in manufacturing.

At the same time as globalization was buffeting the economy, Canadians were heatedly debating the perceived “hollowing out” of the corporate sector as foreigners bought up iconic Canadian firms. Although, as the panel observed, the share of foreign-controlled non-financial firms in Canada remained relatively unchanged, the loss of household names such as Alcan and Inco to foreign control was a stark reminder that companies far from Canada were flexing their muscles to wrest control of well-known firms.

At the heart of the debate was a search for the underlying cause of foreign takeovers. Was a weak dollar or were under-priced natural resources to blame? Was it government policy that had Canadians playing like boy scouts when others were playing like sharks? Finally, was the loss of iconic Canadian firms inevitable or were there steps the government or the private sector could take to stem the flow of takeovers without jeopardizing the health and grow of firms?

Stepping back from the debate, the panel noted an impressive portfolio of Canadian advantages: proximity to the large U.S. market; tidewater to the east, west and north; abundant natural resources including oil and gas, potash and uranium; skilled and motivated workers; and a prudent fiscal regime. However, the panel also noted some important disadvantages. They included a small domestic market, few trade agreements with countries other than the U.S. and Mexico, internal trade barriers, regulations that were not harmonized with our major trading partners and a perceived lack of entrepreneurial culture.

The Panel’s Recommendations

The panel made a total of 65 specific recommendations grouped under several headings (see Appendix 1, page 19). The first group of 17 core recommendations related to the legal foundations of Canada’s competitiveness regime.

Investment Canada Act: The panel recommended that the Investment Canada Act (ICA) review threshold be raised and reporting requirements changed. Further, it recommended that the onus of proof be changed so that it was up to the Ministers of Industry or Canadian Heritage (in the case of cultural industries) to be satisfied that a transaction was contrary to Canada’s national interest before disallowing it. The panel also recommended that transparency around decisions be improved with the Ministers providing the public with more information regarding the ICA process and overall results and specific reports on transactions that are disallowed. In addition, it was recommended that the Ministers review the ICA every five years to ensure that the measures it contains remain relevant.

Sectoral regimes: The panel addressed the treatment of specific industries including air transport, uranium mining, telecommunications and broadcasting, and financial services. The panel recommended that the treatment of transactions in these sectors be reviewed every five years. In the case of air transportation, the panel recommended that the limit on foreign ownership be raised to 49 percent on a reciprocal basis. In the case of uranium mining, the panel recommended that the Minister of Natural Resources liberalize federal policy on foreign ownership of uranium, subject to national security concerns and reciprocity.

In the area of telecommunications and broadcasting, the panel recommended that foreign ownership of telecommunication companies be liberalized in a two-step process. Finally in the area of financial services, the panel recommended that the “widely held” rule be retained and that the Minister of Finance allow so-called “cross-pillar” mergers between financial institutions subject to appropriate safeguards.

Competition Act: The panel considered changes to the Competition Act as well as the ICA in its review of key competition policies. It recommended that the government adopt a two-stage merger review process similar to the one used in the U.S. and that it replace various criminal provisions of the Act with civil provisions. It proposed administrative monetary penalties for abuse of dominance offences. The panel also recommended that a new Canadian Competitiveness Council take on responsibility for competition advocacy and stated that greater use of advanced rulings could improve the timeliness of decisions.

The next group of 48 recommendations related to Canada’s policy regime affecting competitiveness. These recommendations were extremely wide-ranging, touching on diverse issues such as taxation, skills development and immigration, securities regulation, trade and border issues, regulation and intellectual property. Many of the recommendations were aimed at provincial and municipal governments and civil society as well as the federal government.

Taxation: In the area of taxation, the panel recommended that federal and provincial/territorial governments continue their program of reducing corporate tax rates. In addition, provinces were urged to eliminate capital taxes and harmonize their sales tax regimes with the federal goods and services tax. Controversially, the panel also recommended that the federal and provincial/territorial governments make the personal tax system more progressive and shift more of the tax mix from income to consumption. With respect to international corporate taxation, the panel recommended that the federal government consider technical changes to ensure an even playing field related to cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

Post-secondary institutions were urged to pursue greater specialization and to collaborate better with business

Skills: Focusing on skills, the panel made a number of recommendations aimed at post-secondary institutions. For example, it advocated for liberalizing tuition fees and additional merit- and income-based student assistance. Institutions were urged to pursue greater specialization and to collaborate better with business. The panel recommended that governments encourage greater use of co-op terms and internships and take steps to attract more foreign students to Canada.

With respect to immigration, the panel recommended that greater emphasis be placed on economic factors such as Canadian skill shortages in choosing immigrants and that the immigration system be made more responsive to the needs of employers and graduating international students.

Cities: The panel considered the role cities play in contributing to Canada’s competitiveness. The panel urged the federal government to provide leadership with respect to infrastructure as well as the immigration and skills issues discussed above. Controversially, the panel recommended that cities be permitted to levy a one percent value-added tax on the HST base within their jurisdictions to be collected by the Canada Revenue Agency. In addition, municipalities were urged to consider greater use of alternative financing mechanisms such as user fee and public-private partnerships to support spending on critical infrastructure.

The panel argued that government support for SMEs should be focused on firms that have the capacity and desire to grow

Small and medium-sized enterprises: On the subject of fostering the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), the panel argued that government support programs should be focused on firms that have the capacity and desire to grow. Further, it recommended that the Ministers of Finance and Industry develop and release a report on options to increase the supply of private venture capital.

Roles of directors: The panel also weighed in on the subject of the role of company directors when merger or acquisition offers are under consideration. In particular it argued that Canada needed to modernize its regulatory regime and leave substantive oversight of directors’ duties to the courts rather than regulators.

Economic union: The panel focused critical attention on the state of the Canadian economic union and, in particular, barriers to internal trade. It called on the federal and provincial governments to work to eliminate such barriers by 2011. Further, the panel urged the federal government to resolve the issues surrounding national securities regulation quickly and to harmonize federal environmental assessments with those of the provinces, setting timelines as part of a broader national review of environmental assessment practices.

International trade: On the subject of Canada-U.S. economic ties, the panel put a high priority on actions to combat the “thickening” of the border in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. It also urged the federal government to set and achieve ambitious goals for the conclusion of new international trade agreements, adding that the Minister for International Trade should publish annual reports on progress in this area.

Intellectual property and copyright: The panel heard strong views expressed on the subject of intellectual property (IP) and copyright. It recommended that the federal government enact new legislation modernizing its IP laws and strengthening protection against counterfeiting and piracy. It further argued that post-secondary institutions should speed the transfer of university- and college-generated IP to the private sector and noted the University of Waterloo’s innovator-ownership approach as a possible model.

Canadian Competiveness Council: The panel’s final six recommendations focused on the establishment and work of a proposed new body: the Canadian Competitiveness Council. As part of its research, the panel had investigated how other advanced economies monitored and encouraged competitiveness. It determined that the best-in-class was the Australian National Competition Council, which came into existence following a review of the state of competition in Australia in the early 1990s by Professor Fred Hilmer. Professor Hilmer is widely credited with developing the plan that led to the modernization of the Australian economy under successive prime ministers.

Clearly impressed by the Australian experience, the Wilson panel recommended that Canada establish a similar body, independent of government, to examine and report on matters related to competition policy in Canada and to advocate for reforms to improve the state of the country’s competitiveness.

Implementation

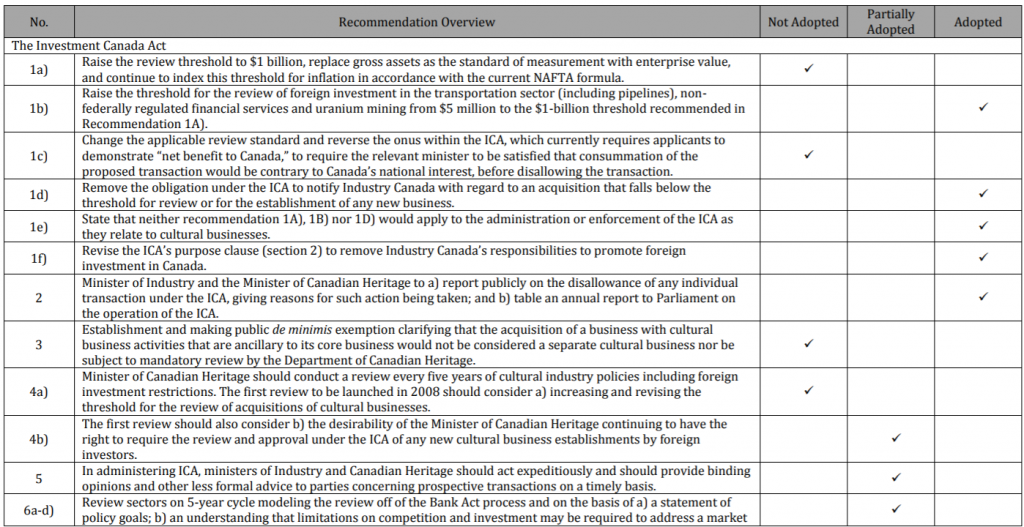

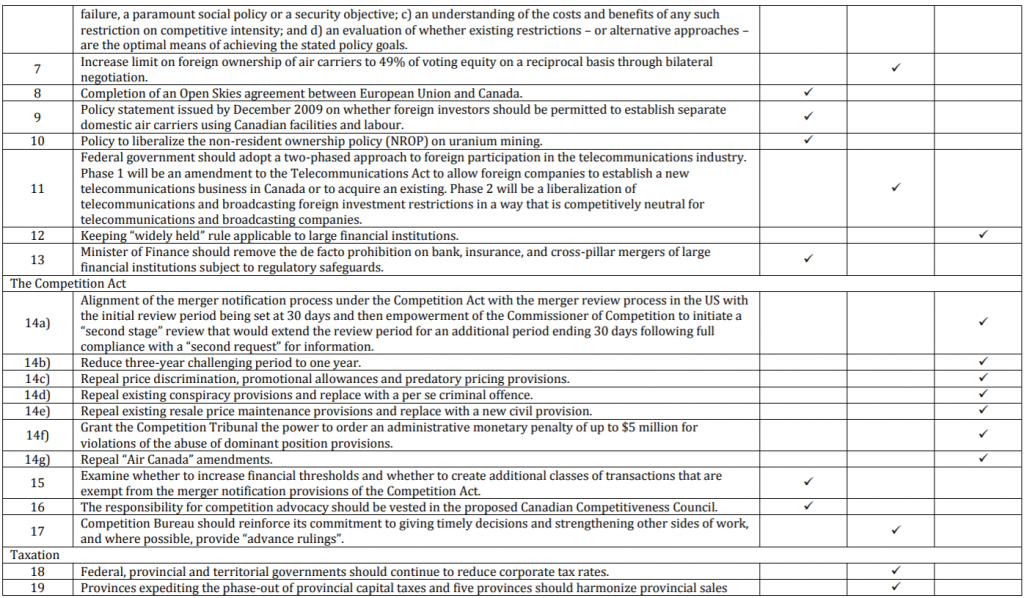

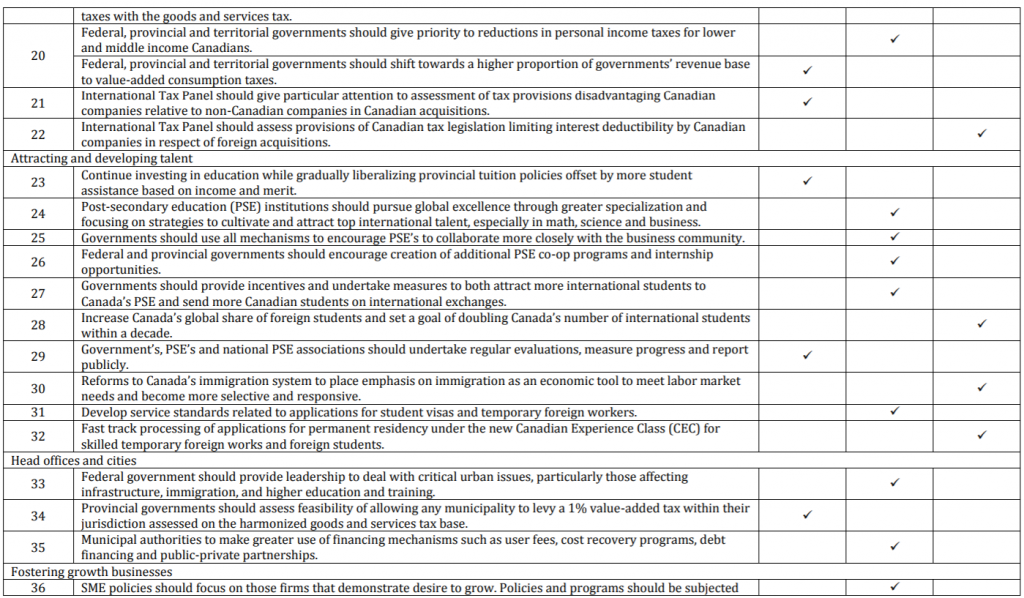

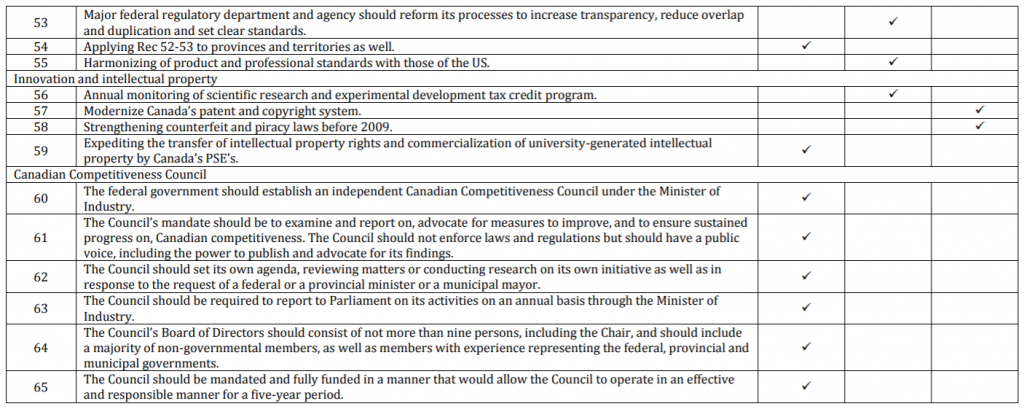

Table 1 (page 29) provides a summary of the government’s progress in implementing the Wilson panel’s recommendation. Below, I provide some additional discussion around selected recommendations.

Investment Canada Act: The government moved to implement some, but not all, of the panel’s ICA-related recommendations. For example, the key recommendation of raising the general review threshold to $1 billion over four years has not yet been implemented. The threshold measure remains asset value, rather than the enterprise value approach that the panel recommended. In addition, the government did not reverse the onus of the review as recommended. On the other hand, the government did eliminate special thresholds for transportation industries, non-regulated financial services and uranium mining. The government also introduced a provision for national security reviews and implemented a mechanism to provide reporting to Parliament regarding ICA activities.

Sectoral regimes: There has been little substantive action to implement the panel’s recommendations regarding foreign ownership of air carriers. In uranium mining, the non-resident ownership policy threshold was raised from 33 to 49 percent. The government did implement the first phase of the Telecommunications Policy Review Panel’s recommendations, allowing foreign companies to establish new companies in Canada or own up to 10 percent of existing companies. However, it has not moved to implement the second phase, the goal of which would be to fully liberalize ownership of telecommunications companies. Finally, the prohibition on cross-pillar mergers of large financial institutions remains in place.

Competition Act: Almost all of the recommendations related to the Competition Act were implemented in some form with a key exception. The responsibility for advocacy was left with the Competition Bureau.

Taxation: Some but not all of the panel’s taxation recommendations have been implemented by federal and provincial governments. General corporate tax rates have been reduced. All general corporate capital taxes have been eliminated. Ontario, BC and PEI harmonized their sales taxes with the federal sales tax, but BC subsequently reversed its harmonization changes. Neither level of government has moved to shift the tax mix from income to consumption taxes.

Skills: Almost all of the panel’s skills recommendations implicated provinces as well as the federal government. To date, responses by governments have been mixed. Tuition fees have been rising on average, but no general “liberalization” has taken place. Some provinces (most recently, Ontario) have taken steps to encourage greater specialization by universities. A number of federal and provincial programs encourage or require collaboration between business and post-secondary institutions. The federal government set a goal to double the number of foreign students in Canada and this number has increased substantially in recent years.

With respect to immigration, recent reforms have increased the emphasis on Canadian labour market needs as the panel recommended. Further, the federal government has made it easier for foreign students to work in Canada for a significant period following graduation, in an effort to retain more of the talent developed in Canadian post-secondary institutions.

It is widely acknowledged that further infrastructure investment is required in major cities such as Toronto and Montreal

Cities: As with skills, many of the panel’s recommendations in this area implicated provincial and municipal governments, as well as the federal government. Governments invested substantially in civic infrastructure as part of the response to the 2009 recession, although it is widely acknowledged that further investment is required in major cities such as Toronto and Montreal. Increasingly, provincial and municipal governments are making greater use of financing mechanisms outside of general taxation. To date, no provincial government has implemented the panel’s recommendation to allow municipalities to levy a one percent sales tax within municipal boundaries.

Small and medium-sized enterprises: The federal government allocated $200 million as part of its response to the 2009 recession to support SMEs, in keeping with the panel’s recommendation. It announced a further investment of $400 million in Budget 2012 to increase private-sector investment in early-stage risk capital, and it continues to provide significant support to business innovation.

Roles of directors: In 2014 the Canadian Securities Administrators and the Quebec regulator, the Autorité des marchés financiers, proposed new harmonized rules to govern directors during mergers and takeovers. Details of the proposals, along with a request for comments, are expected in 2015.

Economic union: Progress on reducing interprovincial trade barriers has been slow, despite media commentary and signs of renewed interest in Ottawa and some provincial capitals. The federal government was strongly rebuffed by the Supreme Court of Canada in its attempt to establish a national securities regulator. The federal government largely abandoned to the provinces the environmental assessment of projects that do not cross provincial boundaries. Mandatory timelines for environmental assessment have been included in legislation, but lack any enforcement mechanism.

International trade: Consistent with the panel’s recommendations, the federal government has invested heavily in the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border Action Plan and, in particular, in moving forward with the proposed new Detroit River International Crossing. In addition to concluding trade agreements with a number of small countries, Canada recently ratified an agreement with Korea and is moving toward ratification of an agreement with the European Union. Canada is also participating in the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations.

On the regulatory front, the government introduced its “one-for-one” rule by which the passing of new regulations is matched by the abolition of an equivalent number of existing regulations. In addition, the Canada-U.S. Regulatory Cooperation Council has continued its work to harmonize regulations and streamline regulatory processes in each country.

Intellectual property and copyright: In Budget 2010, the government established a panel led by Tom Jenkins to review the workings of the Scientific Research and Experimental Development Program. Changes to the program were announced in Budget 2013. In 2012, Parliament passed the Copyright Modernization Act updating Canada’s intellectual property legislation and bringing Canadian laws in line with its World Trade Organization obligations.

Canadian Competitiveness Council: The government has not implement these recommendations.

Assessment

Having reviewed the state of implementation of the panel’s recommendations, it remains to provide an assessment of the government’s response to the panel’s work after six years. The standard for the assessment will be whether the government has, through its implementation of the panel’s recommendations and related actions, made progress in strengthening competition in the Canadian economy. In this section, I focus on a select number of the panel’s recommendations where progress or the lack thereof is particularly noteworthy.

Investment Canada Act: With a number of the panel’s key recommendations in this area unimplemented, along with other key developments, it is fair to say that Canadian foreign investment review policy and practice are in a state of disarray. Key panel initiatives like raising the threshold for investments subject to review are stalled. The implementation of national security reviews has added additional time and uncertainty to the process. The policy on investments by foreign state-owned enterprises that emerged at the time of the CNOOC acquisition of Nexen has created substantial confusion and inhibited investment in Canada by a globally significant source of capital.

It is fair to say that Canadian foreign investment review policy and practice are in a state of disarray

Sectoral regimes: Progress was made with the elimination of some special sectoral thresholds. However, two areas stand out. In the area of air transportation, the government has failed to encourage additional competition as recommended by the panel. In the area of telecommunications, the government has declined to move to the second phase of liberalization recommended by the Telecommunications Policy Review Panel: removing foreign ownership restrictions altogether. In both of these sectors, Canada suffers from a lack of competition and thus Canadians are missing the benefits that some foreign consumers enjoy.

Competition Act: After the Investment Canada Act, the second key pillar of Canadian competition policy is the Competition Act. The government’s response to the panel’s recommendations has been robust and provided a valuable modernization of this important legislation.

Taxation: Although it was probably not a key source of advice on taxation policy, the panel made some useful recommendations and federal and provincial actions in some areas have been consistent with them. Canada now has a best-in-class fiscal regime for business, thanks to the reduction of general corporate tax and elimination of capital taxes, as well as some related measures. As a result, Canada is more attractive to both Canadians and foreigners looking to make greenfield investments.

Some useful tax-related recommendations by the panel were ignored. In particular, governments have declined to shift the burden of personal taxation from income to consumption. Further, they have yet to allow municipalities to levy small consumption taxes to help fund infrastructure investments.

Skills: It is fair to say that governments have made modest progress in the direction recommended by the panel. While useful, none of these initiatives could be considered “liberalization”. Given that business leaders cite skill mismatches as among the greatest challenges to Canada’s economic competitiveness, greater focus in this area by provincial governments is warranted. For example, co-op educational programs have been successful in a number of areas and could be expanded substantially in collaboration with the private sector.

The federal government has taken some important action on the immigration front, streamlining the process and shifting the focus toward bringing skilled labour to Canada

The federal government has taken some important action on the immigration front, streamlining the process and shifting the focus toward bringing skilled labour to Canada. In particular, the changes related to retaining foreign students postgraduation are a source of competitive advantage relative to the U.S.

Economic union: While the federal government has made serious efforts in this area, the results have been disappointing. More notable is the Supreme Court’s decision in favour of the provinces seeking to block a national securities regulator. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce has argued that key remaining internal barriers relate to areas such as the mobility of professionals, government procurement, transportation and agricultural regulation, and energy. The federal move to abandon much of environmental assessment to the provinces means that investors will likely face a patchwork of environmental regimes in the future.

The federal government deserves high marks for its efforts to facilitate and expand trade

International trade: The federal government deserves high marks for its efforts to facilitate and expand trade. Progress on the Beyond the Border Action Plan has been significant and valuable. Efforts to expand Canada’s portfolio of trade agreements are starting to pay off, with agreements with Korea and the European Union being particularly noteworthy.

The Regulatory Cooperation Council continues to work to harmonize regulations and streamline regulatory processes with the U.S. and this work is paying dividends. A recent example is the harmonized emission standard for light-duty vehicles.

In other areas of regulation, however, government initiatives have fallen short. The recently introduced one-for-one rule, however well-intentioned, is overly simplistic and creates incentives that lead to unintended consequences. Such simplistic approaches are no substitute for a careful re-engineering of regulatory processes to maximize efficiency while ensuring the goals of the regulations are met.

Intellectual property and copyright: Attempts to modernize Canada’s IP and copyright regime have been ongoing for a number of years and the lack of progress put Canada increasingly offside with major trading partners. The government deserves credit for successfully modernizing the legislation and providing greater certainty to firms and consumers.

Canadian Competitiveness Council: In researching its report, the panel was struck by contributions made by Professor Fred Hilmer and the Australian National Competition Council in modernizing the Australian economy by opening it up to increased competition. The panel believed that Canada could benefit from a similar body. The role of the council would be to provide independent analysis of the state of competition in Canada and to advocate for reforms to strengthen competition. To governments, such bodies are a mixed blessing. Sometimes such bodies provide independent validation of government initiatives in the face of stakeholder opposition. At other times, they can serve as a reproach in the face of government inaction. Unfortunately, the government declined to implement the panel’s recommendation to establish a Canadian Competitiveness Council. Seeing how much such a body contributed in Australia, this decision can only be seen as a missed opportunity.

Conclusions and Looking to the Future

No one should expect that a government will implement all of the recommendations of an advisory panel and the Competition Policy Review Panel is no exception, especially given its broad scope and the myriad of controversial issues it considered. In addition, the deep and prolonged recession that began in 2009 forced the government to shift its focus from structural reform to short-run stabilization policy. That said, it is reasonable to ask whether the Canadian economy is more competitive today than it was at the time Red Wilson and his colleagues began their work. The answer is mixed.

On the positive side, the government deserves high marks for implementing the panel’s recommendations related to the Competition Act. The Act has been modernized in ways that make it more flexible in its application and created more certainty for firms undertaking mergers. The federal government also deserves credit for its reform of the immigration program and its shift of focus onto skills in deciding who comes to Canada. Reform of the IP and copyright regime is another noteworthy accomplishment. Finally, the federal government has worked diligently at easing trade barriers at the Canada-U.S. border, harmonizing regulations where possible and expanding Canada’s portfolio of trade agreements.

Yet there are several important areas where work remains to be done. In the critical area of foreign investment review, Canada is decidedly worse off today. Not only did the government fail to implement positive reforms recommended by the panel like reversing the onus, raising the threshold and liberalizing sectoral regimes, but the review process has become less certain and more opaque. The government’s policy regarding investments by state-owned enterprises seems arbitrary and confusing. Further, the national security review process has introduced another opaque, time-consuming step potential investors must endure. Lack of progress on the foreign investment review regime is a critical failure that must be addressed.

In the area of sectoral regimes, little progress has been made in introducing more competition into key sectors of the Canada economy such as telecommunications and transportation. The panel’s goal was to inject more competitive pressure into such sectors, both to improve consumer choice and pricing and to help firms prepare to succeed in international markets.

The government not only declined to shift the burden of taxation from income to consumption, but introduced a plethora of personal tax measures that complicate the tax system

While governments have substantially improved the business tax regime, they missed the opportunity to give municipal governments greater capacity to address infrastructure needs. The federal government in particular not only declined to shift the burden of taxation from income to consumption, but introduced a plethora of personal tax measures that fragment and complicate the tax system.

Finally, the government missed an important opportunity to create an ongoing focus on competition by declining to implement the panel’s recommendation to establish a Canadian Competition Council.

Given the mixed success in the implementation of the panel’s recommendations, what should be the key priorities for further reform following the next general election? I believe that three areas require urgent attention.

The first area is foreign investment review. Further reform of the Investment Canada Act reform should be near the top of the government’s economic priority list. Canada benefits from foreign investment both because of the increase in economic activity and because of the increased competition such investments bring.

We cannot afford to be branded as “closed for business” by the big international capital pools, including those with government backing. Simplifying, clarifying and streamlining the review process is an urgent priority.

Efforts to raise the threshold for review have been bogged down over the issue of enterprise value. Clearly, given the time that has passed, this issue is more complex than the panel realized. Moving forward on a rising threshold based on book value would be a valuable step.

We cannot afford to be branded as ‘closed for business’ by the big international capital pools

The treatment of investments by state-owned enterprises – and entities that may be related to them or are otherwise captured by this policy – creates uncertainty and isolates one of the largest pools of global investment capital. The previous policy required SOEs to conduct themselves in keeping with good business practices and govern themselves in the same way as companies listed on recognized stock exchanges. This policy established an appropriate standard of behavior for these investors. The new policy creates uncertainty regarding the definition of an SOE and how it or related entities can pass the ICA’s net-benefit test.

Finally, national security reviews have added additional uncertainty and time to an already opaque and time-consuming process. The government needs to design a process that will enable it to protect Canada’s security interests while providing investors with greater clarity with respect to the way they will be treated and how long it will take to complete the process.

The second area that demands urgent action is sectoral reform. The government’s efforts to introduce additional competition into the telecom sector by setting aside spectrum for new entrants have met with limited success. If increased competition remains the goal, it is now time to consider allowing foreign firms to enter the Canadian market on an equal footing with large incumbents. It may be, as some incumbents argue, that the sector is already as competitive as possible given the technological demands put on full-service national telecom companies. However, only by moving to the next step in liberalizing the sector will we know whether additional firms will improve consumer choice and pricing. Any increase in competitive pressure in the domestic market might have the further benefit of encouraging Canadian telecom firms to venture forth and become international competitors.

In the area of air transportation, Canada remains a market dominated by two large carriers. Greater competition in this sector could yield large benefits to consumers, especially those traveling internationally. Canada should move ahead with measures to loosen foreign ownership restrictions and push forward to conclude additional “open skies” agreements with jurisdictions beyond Europe.

Finally, the government missed an important opportunity to ensure a sustained focus on competition by declining to establish the proposed Canadian Competition Council. Australia’s competition council has played a vital role in encouraging the modernization of that country’s economy. While the recommendations of such a council are sometimes inconvenient for governments of the day, they provide a forum for analyzing and debating measures to enhance competitiveness and can remind us of the competition consequences of policies that governments pursue for other reasons. Given the current government’s increasing reliance on analysis produced by outside groups, Canada needs such a body to provide independent, expert advice on the path forward for economic reform.

In sum, the Competition Policy Review Panel laid out an ambitious reform agenda for the federal government. The government has made important progress in a number of key areas. Unfortunately, progress in those areas has been overshadowed by the increasing disarray of the foreign investment review regime, lack of progress in increasing sectoral competition, and the government’s failure to appoint a body that would ensure a sustained focus on increasing competition in the Canadian economy. In these areas in particular, much remains to be done if we are to “compete to win”.

Appendix 1: Competition Policy Review Panel Recommendations

The Investment Canada Act

- The Minister of Industry should introduce amendments to the Investment Canada Act as follows:

a. Raise the review threshold to $1 billion, replace gross assets as the standard of measurement with enterprise value of the acquired business, and continue to index this threshold for inflation in accordance with the current NAFTA formula;

b. Raise the threshold for the review of foreign investment in the transportation sector (including pipelines), non-federally regulated financial services and uranium mining from $5 million to the $1-

billion threshold recommended above;

c. Change the applicable review standard and reverse the onus within the ICA, which currently requires applicants to demonstrate “net benefit to Canada,” to require the relevant minister to be satisfied that consummation of the proposed transaction would be contrary to Canada’s national interest, before disallowing the transaction;

d. Remove the obligation under the ICA to notify Industry Canada with regard to an acquisition that falls below the threshold for review or

for the establishment of any new business;

e. State that neither recommendation 1.a, 1.b nor 1.d would apply to the administration or enforcement of the ICA as they relate to cultural businesses; and

f. Revise the ICA’s purpose clause (section 2) to remove Industry Canada’s responsibilities to promote foreign investment in Canada.

- The Minister of Industry and the Minister of Canadian Heritage should increase the use of guidelines and other advisory materials to provide information to the public concerning the review process, the basis for making decisions under the ICA, and interpretations by Industry Canada and the Department of Canadian Heritage regarding the application of the ICA. Additionally, amendments to the ICA should require the Ministers to:

a. Report publicly on the disallowance of any individual transaction

under the ICA, giving reasons for such action being taken; and

b. Table an annual report to Parliament on the operation of the ICA. - The Minister of Canadian Heritage should establish and make public a de minimis exemption clarifying that the acquisition of a business with cultural business activities that are ancillary to its core business would not be considered a separate cultural business nor be subject to mandatory review by the Department of Canadian Heritage. For the purpose of applying this exemption, the cultural business activities would be considered de minimis if the revenues from cultural business activities are less than the lesser of $10 million or 10 percent of gross revenues of the overall business.

- Consistent with recommendations for other sectors, the Minister of Canadian Heritage, with advice from stakeholders and other interested parties, should conduct a review every five years of cultural industry policies, including foreign investment restrictions. The first such review should be launched in 2008. As a matter of priority, the first review should consider:

a. Increasing and revising the threshold for the review of acquisitions of cultural businesses; and

b. The desirability of the Minister of Canadian Heritage continuing to

have the right to require the review and approval under the ICA of any new cultural business establishments by foreign investors. - In administering the ICA, the ministers of Industry and Canadian Heritage should act expeditiously and give appropriate weight to the realities of the global marketplace and, in appropriate cases, the ministers should provide binding opinions and other less formal advice to parties concerning prospective transactions on a timely basis to ensure compliance with the ICA.

Sectoral regimes

- Individual ministers responsible for the sectors addressed in this report should be required to conduct a periodic review of the sectoral regulatory regime with a view to minimizing impediments to competition as well as updating and adapting the regulatory regime to reflect the changing circumstances, needs and goals of Canada. This review should be modeled on the Bank Act process and should occur on a five-year cycle. Ownership restrictions should be reviewed on the basis of:

a. A statement of policy goals that reflect the current Canadian reality;

b. An understanding that limitations on competition and investment

may be required to address a market failure, a paramount social policy or a security objective;

c. An understanding of the costs and benefits of any such restriction on competitive intensity; and

d. An evaluation of whether existing restrictions—or alternative

approaches — are the optimal means of achieving the stated policy

goals.

Air transport

- The Minister of Transport should increase the limit on foreign ownership of air carriers to 49 percent of voting equity on a reciprocal basis through bilateral negotiation.

- The Minister of Transport should complete Open Skies negotiations with the European Union as quickly as possible.

- The Minister of Transport, on the basis of public consultations, should issue a policy statement by December 2009 on whether foreign investors should be permitted to establish separate Canadian-incorporated domestic air carriers using Canadian facilities and labour.

Uranium mining

- The Minister of Natural Resources should issue a policy directive to liberalize the non-resident ownership policy on uranium mining, subject to new national security legislation coming into force and Canada securing commensurate market access benefits allowing for Canadian participation in the development of uranium resources outside Canada or access to uranium processing technologies used for the production of nuclear fuel for nuclear power plants.

Telecommunications and broadcasting

- Consistent with the Telecommunications Policy Review Panel Final Report 2006, the federal government should adopt a two-phased approach to foreign participation in the telecommunications and broadcast industry. In the first phase, the Minister of Industry should seek an amendment o the Telecommunications Act to allow foreign companies to establish a new telecommunications business in Canada or to acquire an existing telecommunications company with a market share of up to 10 percent of the telecommunications market in Canada. In the second phase, following a review of broadcasting and cultural policies including foreign investment, telecommunications and broadcasting foreign investment restrictions should be liberalized in a manner that is competitively neutral for telecommunications and broadcasting companies.

Financial services

- The “widely held” rule applicable to large financial institutions should be retained.

- The Minister of Finance should remove the de facto prohibition on bank, insurance and cross-pillar mergers of large financial institutions subject to regulatory safeguards, enforced and administered by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions and the Competition Bureau.

The Competition Act

- The Minister of Industry should introduce amendments to the Competition Act as follows:

a. Align the merger notification process under the Competition Act

b. More closely with the merger review process in the United States; the initial review period should be set at 30 days, and the Commissioner of Competition should be empowered, in its discretion, to initiate a “second stage” review that would extend the review period for an additional period ending 30 days following full compliance with a “second request” for information;

c. Reduce to one year the three-year period within which the

Commissioner of Competition currently may challenge a completed

merger;

d. Repeal the price discrimination, promotional allowances and predatory pricing provisions;

e. Repeal the existing conspiracy provisions and replace them with a per se criminal offence to address hardcore cartels and a civil provision to deal with other types of agreements between competitors that have anticompetitive effects;

f. Repeal the existing resale price maintenance provisions and replace

them with a new civil provision to address this practice when it has an

anti- competitive effect. This new provision should be subject to the

private access rights before the Competition Tribunal;

g. Grant the Competition Tribunal the power to order an administrative monetary penalty of up to $5 million for violations of the abuse of dominant position provisions; and

h. Repeal the “Air Canada” amendments that created special abuse of

dominant position rules and penalties for a dominant air passenger

service. - The Minister of Industry should examine whether to increase the financial thresholds that trigger an obligation to notify a merger transaction as well as whether to create additional classes of transactions that are exempt from the merger notification provisions of the Competition Act.

- The responsibility for competition advocacy should be vested in the

proposed Canadian Competitiveness Council. The power to undertake

interventions before regulatory boards and tribunals under sections 125 and 126 of the Competition Act should remain with the Commissioner of Competition, unless and until such powers are granted to the proposed Council. - The Competition Bureau should reinforce its commitment to giving timely decisions, strengthen its economic analysis capabilities, give appropriate weight to the realities of the global marketplace and, where possible, provide “advance rulings” and other less formal advice to parties concerning prospective transactions and other arrangements on a timely basis to ensure compliance with the Competition Act.

Competitiveness Agenda: Public policy priorities for action

Taxation

- The federal, provincial and territorial governments should continue to

reduce corporate tax rates to create a competitive advantage for Canada, particularly relative to the United States. - Provinces should expedite the phase-out of provincial capital taxes, and the provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island should move expeditiously to harmonize their provincial sales taxes with the goods and services tax.

- The federal, provincial and territorial governments should give priority to reductions in personal income taxes, particularly for lower- and middleincome Canadians, and should provide incentives for investment and work by shifting a higher proportion of governments’ revenue base to value-added consumption taxes.

- The International Tax Panel should give particular attention to an

assessment of tax provisions disadvantaging Canadian companies relative to non-Canadian companies in Canadian acquisitions, with the objective of recommending ways to allow Canadian-based companies to compete on an equal footing. - The International Tax Panel should assess the provisions of Canadian tax legislation limiting interest deductibility by Canadian companies in respect of foreign acquisitions to ensure that Canadian companies seeking to compete globally enjoy every advantage relative to their foreign competitors.

Attracting and developing talent

- Governments should continue to invest in education in order to enhance quality and improve educational outcomes while gradually liberalizing provincial tuition policies offset by more student assistance based on income and merit.

- Post-secondary education institutions should pursue global excellence

through greater specialization, focusing on strategies to cultivate and attract top international talent, especially in the fields of math, science and business. - Governments should use all the mechanisms at their disposal to encourage post-secondary education institutions to collaborate more closely with the business community, cultivating partnerships and exchanges in order to enhance institutional governance, curriculum development and community engagement.

- Federal and provincial governments should encourage the creation of

additional post-secondary education co-op programs and internship

opportunities in appropriate fields, to ensure that more Canadians are

equipped to meet future labour market needs and that students gain

experiences that help them make the transition into the workforce.

- Governments should provide incentives and undertake measures to both attract more international students to Canada’s post-secondary institutions and send more Canadian students on international study exchanges.

- Governments should strive to increase Canada’s global share of foreign students, and set a goal of doubling Canada’s number of international students within a decade.

- Governments, post-secondary education institutions and national postsecondary education associations should undertake regular evaluations, measure progress and report publicly on improvements in business– academic collaboration, participation in co-op programs, and the attraction and retention of international talent.

- Reforms to Canada’s immigration system should place emphasis on

immigration as an economic tool to meet our labour market needs, becoming more selective and responsive in addressing labour shortages across the skills spectrum. - Canada’s immigration system should develop service standards related to applications for student visas and temporary foreign workers, and should be more responsive to private employers and student needs by fast-tracking processing and providing greater certainty regarding the length of time required to process applications.

- In order to ensure that Canada is able to attract and retain top international talent, and respond more effectively to private employers, Canada’s immigration system should fast track processing of applications for permanent residency under the new Canadian Experience Class for skilled temporary foreign workers and foreign students with Canadian credentials and work experience

Head offices and cities

- Given the national importance of Canada’s largest urban centres, the federal government should provide leadership to deal with critical urban issues, particularly those affecting infrastructure, immigration, and higher education and training.

- In addressing urban issues, municipalities need a more stable, secure and growing revenue source. In particular, provincial governments should assess the feasibility of allowing any municipality to levy a 1 percent value-added tax within their jurisdiction, assessed on the harmonized goods and services tax base, which would be collected by the Canada Revenue Agency (or Revenue Quebec) on behalf of the municipality.

- In dealing with these issues, municipal authorities that have not already done so should make greater use of financing mechanisms such as user fees, cost recovery programs, debt financing and public–private partnerships.

Fostering growth business

- Federal and provincial governments’ small and medium-sized enterprise policies should focus on those firms that demonstrate the desire and capacity to grow to become large enterprises. Small and medium-sized enterprise policies and programs should be subjected to regular review in order to assess and measure whether this objective is being met.

- The Minister of Finance and the Minister of Industry should develop and release a public report on options, including tax incentives, to facilitate the provision of more private venture capital, particularly at the “angel” and late stage, by June 2009.

Strengthening the role of directors in mergers and acquisitions

- Securities commissions should repeal National Policy 62-202 (Defensive Tactics).

- Securities commissions should cease to regulate conduct by boards in

relation to shareholder rights plans (“poison pills”). - Substantive oversight of directors’ duties in mergers and acquisitions

matters should be provided by the courts. - The Ontario Securities Commission should provide leadership to the

Canadian Securities Administrators in making the above changes, and initiate action if collective action is not taken before the end of 2008.

The Canadian Economic union

- The federal government should provide leadership in the elimination of all internal barriers between the provinces and territories that inhibit the free flow of goods, services and people by June 2011.

- Federal and provincial governments should establish by June 2009 a work plan to achieve this goal and provide interim reports on progress every six months.

- The federal government should show leadership regarding national

securities regulation and resolve this matter expeditiously. - The federal government should more fully harmonize federal environmental assessment procedures with provincial processes.

- Beginning January 2009, the federal government should abide by timelines that are not longer than the environmental assessment timelines set by the relevant provincial jurisdiction for a proposed project subject to assessment and incorporate such timelines as part of the broader national review required for 2010.

Canada-US Economic ties

- Addressing the thickening of the Canada–US border should be the number one trade priority for Canada, and requires heightened direct bilateral engagement at the highest political levels.

- Canada should act to create a more seamless US border crossing process, focusing on priorities jointly identified by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce and US Chamber of Commerce in their February 2008 report, while responding to legitimate US security needs, and funding and expediting vital border infrastructure.

International trade and investment

- The federal government should set an ambitious timeline for concluding priority trade and investment agreements, led by the Minister of International Trade who should pursue a flexible, results-based approach, beginning by simplifying Canada’s model foreign investment protection agreements and streamlining our free trade agreements negotiating processes.

- Beginning in 2009, on behalf of the federal government, the Minister of International Trade should report at least annually on Canada’s trade and investment liberalization initiatives generally and in specific sectors.

- Beginning immediately, the Minister of International Trade should build on the Global Commerce Strategy by developing and publicizing annual plans and priorities for enhanced trade and investment, and by identifying priority trading partners, economic impacts of prospective agreements and services to businesses. Comprehensive input from business should guide and inform Canada’s approach across government.

Regulation

- A senior federal economic minister should be mandated to lead and oversee progress on regulatory reforms, implementing a new regulatory screen by June 2009 that would subject all new regulations to a rigorous assessment of their impact on competitiveness.

- Each major federal regulatory department and agency should reform its processes to increase transparency, reduce overlap and duplication, and set clear standards to yield time certain decisions, reporting annually, commencing in 2010, on outcomes and performance.

- The foregoing recommendations for regulatory reform are equally applicable to provinces and territories.

- Canada should harmonize its product and professional standards with those of the US, except in cases where, and then only to the extent that, it can be demonstrated that the impairment of the regulatory objective outweighs the competitiveness benefit that would arise from harmonizing.

Innovation and intellectual property

- The federal government should monitor the scientific research and

experimental development tax credit program annually in order to ensure that business investment in research and development and innovation in Canada is effectively encouraged. - As a matter of priority, the federal government should ensure that new copyright legislation will both sufficiently reward creators while stimulating competition and innovation in the Internet age. Any prospective changes to Canada’s patent law regime should also reflect this balance. The federal government should assess and modernize the Canadian patent and copyright system to support the international efforts of Canadian participants in the global economy in a timely and effective manner.

- Before December 2009, the federal government should strengthen

counterfeit and piracy laws to ensure that intellectual property rights are effectively protected.

- Canada’s post-secondary education institutions should expedite the transfer of intellectual property rights and the commercialization of universitygenerated intellectual property. One possible method to achieve this would be to move to an “innovator ownership” model to speed commercialization.

Driving Change: A Canadian Competitiveness Council

- The federal government should establish as expeditiously as possible

independent Canadian Competitiveness Council under the Minister of

Industry. The Council should be staffed by a Chief Executive Officer and a small core staff, overseen by a Board of Directors. - The Council’s mandate should be to examine and report on, advocate for measures to improve, and to ensure sustained progress on, Canadian competitiveness. The Council should not enforce laws and regulations but should have a public voice, including the power to publish and advocate for its findings.

- The Council should set its own agenda, reviewing matters or conducting research on its own initiative as well as in response to the request of a federal or a provincial minister or a municipal mayor. Governments should not have the power to compel the Council to undertake or discontinue a review or study.

- The Council should be required to report to Parliament on its activities on an annual basis through the Minister of Industry.

- The Council’s Board of Directors should consist of not more than nine

persons, including the Chair, and should include a majority of nongovernmental members, as well as members with experience representing the federal, provincial and municipal governments. - The Council should be mandated and fully funded in a manner that would allow the Council to operate in an effective and responsible manner for a fiveyear period. Prior to the end of the five-year period, the Minister of Industry should undertake a review to determine whether the Council’s mandate should be renewed and, if so, on what terms.

Table 1: Implementation of panel recommendations