Chasing China: Why an economic agreement with China is necessary for Canada’s continued prosperity

Executive Summary

China is Integral to Canada’s Economic Strategy

With a GDP more than six times that of Canada’s and growth that is three times faster than Canada’s, China is quickly becoming the world’s largest economy. Although Canada has been increasing its economic relationship with China, its approach has been inconsistent, even as China is aggressively securing partnerships with other western countries. Canada risks being left out of China’s economic growth plans, to the detriment of Canadian manufacturers and exporters.

Economic Benefits of Increased Trade With China

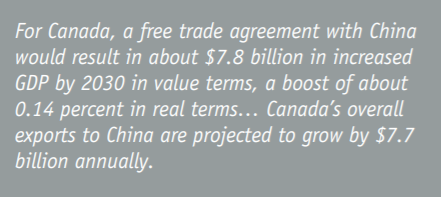

A free trade agreement between Canada and China would increase Canadian exports by some $7.7 billion and Canadian GDP by about $7.8 billion (or 0.14%) by 2030, helping to create an additional 25,000 Canadian jobs across all skill levels, raising wage rates as the demand for Canadian labour increases.

At the sectoral level, annual automotive exports to China will increase by more than $1.4 billion, chemicals/rubber/ plastics by some $688 million, machinery and equipment by $584 million, and approximately $1.7 billion more in exports of oil seeds and vegetable oil.

Economic gains would also be generated through lower-priced imports for consumers and manufacturers. Deepened trade with a large and growing market will mark an important turning point in Canada’s trade diversification away from the United States, towards the world.

The Competition is Moving Past Us

The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) signed in June 2015 provides many best-ever commitments from China, eliminating 95 percent of tariffs within a decade. Australia will benefit from reduced or eliminated

tariffs for key export sectors and increased access for service providers. Australia’s gains in China will displace Canadian exporters of competing goods and services until Canada achieves similar market access commitments. On the positive side, the ChAFTA provides a template for an agreement text with China that will accelerate Canada’s negotiating process.

The Path Ahead

Canada has a narrow window in which to negotiate closer economic ties with China but, after delaying for a decade, the window is rapidly closing. The assumptions about mutual economic complementarity that prompted the commitment to closer ties become less relevant with every year that passes. At the same time, the election of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau provides an important opportunity to reset the relationship, especially given the extraordinarily high esteem that the Chinese still maintain

for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau; he was the first Canadian prime minister to visit China and he led other western countries in granting official diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China.

If Canada were to become the first country in the Americas to secure a trade deal with China, it would not only benefit from direct trade opportunities, it would also be a magnet for investors from third countries wishing to take advantage of Canada’s privileged access. Australia has shown that a meaningful trade deal with China can be negotiated and Australian companies now have an advantage in almost every area in which they compete with Canada.

Why an economic agreement with China is necessary for Canada’s continued prosperity

Pierre Trudeau was one of the first world leaders to grant diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), setting in motion a framework for engagement that spans nearly five decades. During the Chretien era, Premier Zhu Rongji described Canada as a “best friend” of China. In 2005, China granted Canada strategic partnership status – a high-level relationship that signals Canada’s importance “to the multiple layers of the Chinese government and to its firms.”

Building on this strategic partnership, the roadmap for closer economic engagement was laid out in the 2012 Canada-China Economic Complementarities Study produced by the two governments. It provides a detailed agenda for closer trade relations, both in traditional areas of interest such as resources and agriculture, as well as new areas such

as technology and sustainable development. This was a peak period in bilateral relations, marked by the conclusion of negotiations for a Foreign Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement (FIPA) and amendments to the Canada-China Nuclear Cooperation Agreement allowing sales of Saskatchewan uranium to Chinese nuclear power plants.

But Chinese investment in Canada’s energy sector, particularly the 2013 acquisition of Nexen by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), spooked the Government of Canada and its Cabinet and triggered a wave of suspicion about Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) activity, resulting in stricter rules clearly intended for China. The Harper government wavered in its support for closer ties with China. Almost overnight any discussion of formalizing a free trade agreement with China disappeared, even as Canada launched negotiations with other Asian partners through the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

With Canada sending mixed signals, China has moved on to other partners, completing free trade agreements with Australia and South Korea in 2015.

Australia’s privileged market access will make Canada’s competing exports in key sectors such as pork and coal up to 20 percent more expensive, in relative terms, for Chinese buyers.

The window of opportunity has not closed entirely. China continues to make welcoming overtures to Canada and securing the renminbi (RMB) hub in 2015 indicates that all is not lost. But China’s patience cannot last forever.

Nor can the benefits identified in the 2012 Canada-China Economic Complementarities Study continue to be relevant in a changing global economy.

In November 2014, Prime Minister Harper and Premier Li Keqiang agreed to a Foreign Affairs Ministers Dialogue and a Canada-China Economic and Financial Strategic Dialogue that was set to begin in 2015. Canada once again failed to take the advantages offered and neither of these dialogues

have been set in motion, despite the non-threatening contribution these initiatives could make to improved understanding and closer cooperation. Even the planned step of launching a civil society dialogue as a pre-cursor to the FTA was continually delayed by the Harper government. A further example of Canadian ambivalence was turning down the opportunity to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in June 2015.

China is worth the effort. The country is still on track to become the world’s largest economy by 2030. In September 2015, China, not Canada, ranked as the United States’ largest trading partner for the first time. Even though recent declines have pushed China’s annual growth forecasts down from more than 7 percent to around 6.5 percent, this is still much faster than growth rates in the United States or Canada (see Table 1).

Meanwhile, Canadians remain concerned about cybersecurity and industrial espionage, not to mention human rights and territorial expansion. As David Mulroney, a former Canadian Ambassador to China, says, the idea is not to ignore fundamental differences but to find ways to manage the difficulties. This cannot be achieved without clear lines of engagement and communication.

Doing nothing does not mean staying the same, it means falling further behind. Canada must act quickly and decisively to ensure that the China-sized hole in Canada’s trade policy does not create lasting damage from which we cannot recover. Moreover, economic engagement cannot exist without participation in regional and bilateral dialogues on security, stability, society and the environment. The U.S.-China relationship will be the focal point of international relations in the coming decades. Without a plan for managing relations between two giants, Canada risks getting stepped on or pushed aside.

Why Does Trade With China Matter?

Canada has been attempting to diversify away from the United States by deepening trade ties around the world. Free trade agreements (FTAs) have been brought into force with Peru (2009), Colombia (2011), Jordan (2012), Panama (2013), Honduras (2014) and South Korea (2015). Canada has also concluded negotiations with the European Union (2014), Ukraine (2015) and TPP member countries (2015). What is notable, however, is that with the exception of the European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade agreement and the TPP, few of these agreements represent significant market potential for Canada and only a handful of countries (South Korea, Colombia, Peru) could be considered fast growing.

With Canada negotiating trade agreements around the world, China is the glaring omission. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced near the end of 2014 that, adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), China had overtaken the United States as the world’s largest economy in real terms. Although the absolute size of China’s economy is still smaller than the U.S., when adjusted for purchasing power, China’s GDP in 2014 stood at US$17.6 trillion compared to the US$17.4 trillion for the United States. Although many are debating the future momentum of China’s growth, its continued positive growth and its importance as a global market is incontrovertible.

Canada-China Economic Profile

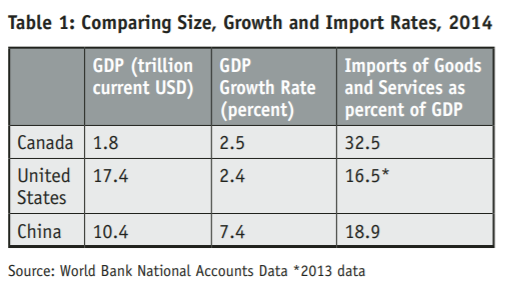

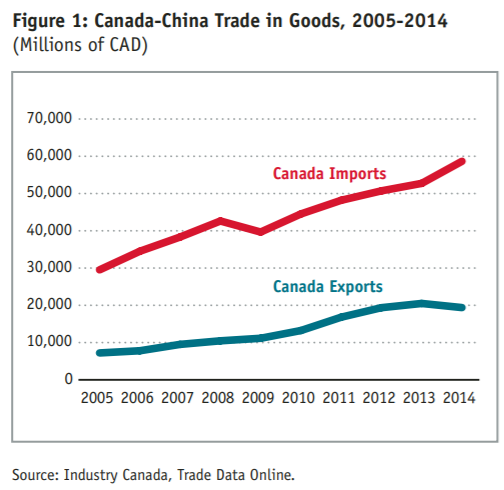

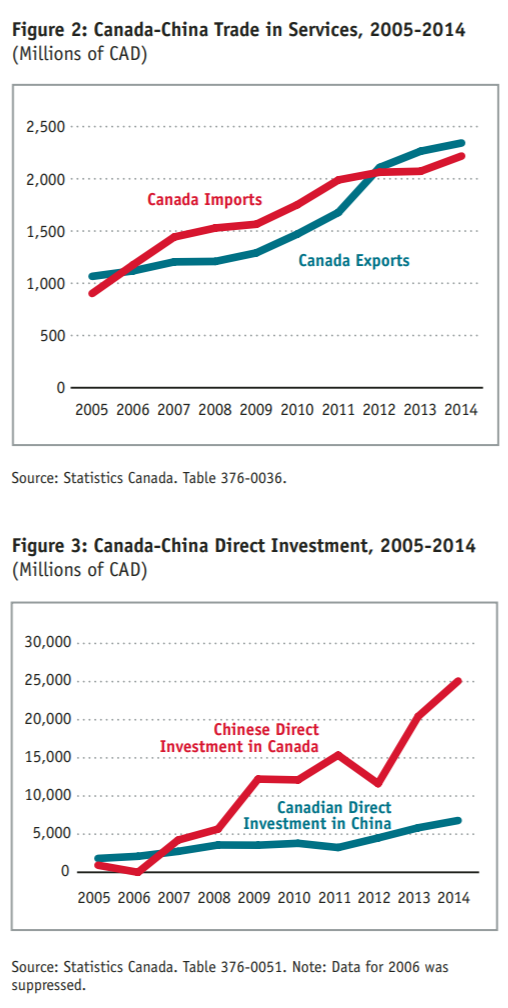

China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner. By 2014, two-way bilateral merchandise trade totaled $78 billion, up 53.6 percent over the previous five years. Total foreign direct investment (FDI) between Canada and China increased more than eleven times between 2005 and 2014, to a total of $31.8 billion. FDI in Canada from China reached $25.1 billion in 2014, a 27-fold increase over ten years. Note that the Statistics Canada data does not include Chinese investment coming to Canada through third countries. When these figures are added, the China Institute at the University of Alberta estimates that the stock of Chinese FDI in Canada stands at about

$60 billion.

Good But Not Great

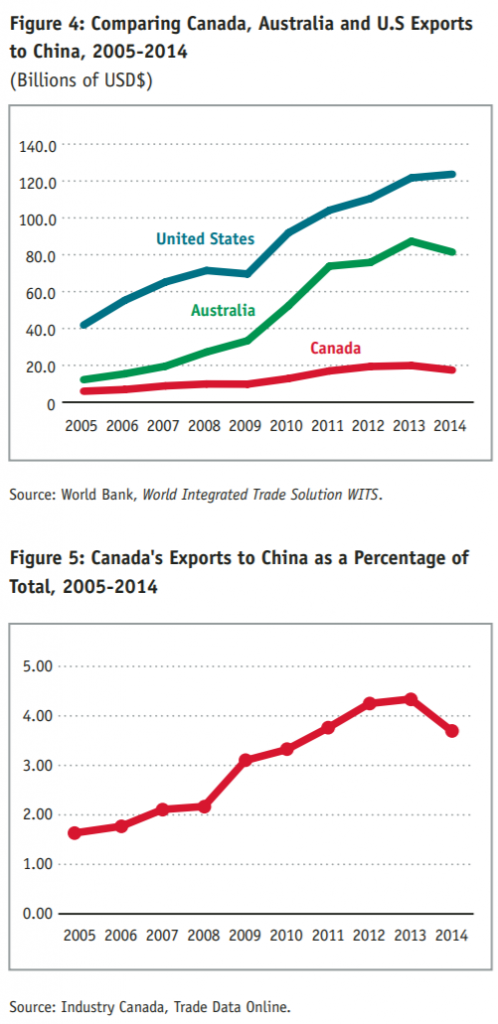

As Figures 1 through 3 illustrate, Canada’s trade and investment relationship with China has been increasing in absolute terms but, in relative terms, Canada is not keeping up with the competition. From Figure 4 it is clear that both Australia and the United States are outpacing Canada in terms of export growth. And a closer look at Canada’s exports to China (Figure 5) shows minimal or negative growth since 2012.

Key Elements of Chinese Demand

If the Government of Canada decided to focus its trade strategy on capturing a larger share of Chinese demand, what would this demand look like? What are the areas of complementarity?

Chinese demand is driven by the need for energy and minerals to fuel its transformation to a modern, developed economy that can sustain 1.3 billion people. McKinsey & Company estimate that China will account for over 40 percent of the global growth in energy demand by 2030.

Canadian oil shipments to China are negligible (less than 2 percent of exports) due to producers’ inability to transport oil to deep water ports (except for transshipments through the United States). Changes in domestic pipeline infrastructure could break the chokepoints but, in the meantime, China is a rich market for Canadian coal and potash.

China consumes 50 percent of the world’s thermal coal and accounts for 20 to 30 percent of the world’s coal imports, but that level is expected to peak in the next five years as investments in renewable energy begin to pay off. As one of the top eight global exporters of coal, Canada has a short but lucrative market window. Meanwhile, Saskatchewan’s Canpotex is helping to meet China’s demand for fertilizer. In 2014, Canada exported nearly $400 million in potash to China and Canpotex has supply contracts in

place to guarantee sales volumes through 2017.

Despite its reliance on traditional energy sources, the Chinese government recognizes the environmental stresses created by economic transformation and it is making massive investments in green technology. China was responsible for a third of global spending on clean energy in 2014, some $89.5 billion. In order to help cut carbon emissions, the Chinese government is committed to obtaining 20 percent of its energy from renewables and nuclear power by 2030. This represents a major opportunity for Canada. Clean technology is one of Canada’s fastest growing sectors, expanding by nearly 10 percent a year since 2011.

By 2030, there will be some 2 billion consumers in the Asian middle class, requiring major investments in physical and social infrastructure to sustain them. In China alone, it is estimated that there will be 326 million new urban middle-class consumers created between 2014 and 2030 and the total middle class population will reach 854 million by 2030, the largest middle class of any country in the world.

Canada is well placed to serve China’s demand for goods and services related to rapid urbanization. China has gone from a 30 percent urbanization rate in 1994 to 53 percent in 2014, meaning that roughly 300 million people (a quarter of China’s population) have moved from the countryside to cities in just two decades. Building cities and moving people requires building materials – such as Canadian wood products – and transportation – such as Canadian rail cars and aircraft – and the engineering and transportation know-how to make it all work. The importance of exporting knowledge-based services has taken on a greater urgency as November 2015 Statistics Canada data shows the highest rates of professional, scientific, and technical job loss in Canada since the recession.

The expansion of China’s cities also means that fewer people are in the countryside growing their own food, thus the demand for imported food is rising sharply. What is more, the higher incomes of city-dwellers means that more Chinese consumers can afford the variety and novelty of imported food products. Imports of food, live animals (used mainly for food), oils, beverages and tobacco increased from US$2.3 billion in 1994 to US$100.8 billion in 2013.

Proteins are particularly important. China’s market for meat is expected to grow by 60 percent by 2030. Steady increases are predicted for imports of pork, beef and poultry as well as grains and legumes. However, with the concessions China has made to Australia in ChAFTA (discussed later in this report), Canada’s meat sector may be pushed out of China’s market.

Oilseed products, particularly canola, are key to Canada’s export prospects. In 2013-2014 Chinese demand accounted for nearly two-thirds of all global oilseed shipments. In 2014, canola was the number one Canadian export to China, valued at nearly $2.3 billion.

The relationship between Canada and China has grown beyond trade in goods. Person-to-person connections have generated rising levels of immigration and temporary movement. In 2013 there were over 1.3

million Canadians of Chinese heritage and 1.1 million Canadians claimed a Chinese language as their mother tongue in the 2011 Census.

An increase in personal linkages is accompanied by increased consumption of related services such as education and tourism as well as commercial and real estate investment. More than 128,000 Chinese nationals held a valid study permit at some point in 2014, with an estimated economic impact of about $4 billion annually.

Approximately 410,000 Chinese tourists visited Canada in 2013 and that number is expected to increase by 20 percent every year. China is Canada’s top source of foreign students, one of the top three sources of immigrants and the fourth largest source of tourists.39 While the populations of the two countries are inextricably linked, the full benefit of economic synergies has not yet been realized.

Without a comprehensive China economic strategy, Canada will have only weak market opportunities for some of its most important industries. A China strategy helps Canada to diversify away from dependence on slow-growth economies such as the United States and European Union and to develop nascent industries where Canada has the potential to grow into a global leader, such as green technology.

The Policy Dimension: Cool Politics and Warm Economics

Canada’s engagement with China over the past decade has been characterized by leads and lags, much of which may be attributed to the Harper government strategy of attempting to generate warm economics while maintaining cool politics.

Between 2009 and 2012, Canada’s economic relationship with China grew on many fronts as the two countries explored the economic complementarities that might lead to a free trade agreement and sought to deepen investment linkages through a FIPA. However, China’s aggressive

investment in Canada made Canadians nervous. CNOOC’s acquisition of Nexen raised uncomfortable questions about how much foreign ownership – and in particular Chinese ownership – Canadians were willing to accept on home soil. Canada approved the sale, even as it implemented stiffer rules for SOEs. Evans identifies this as the turning point away from a productive period of engagement: “In 2012, the momentum was broken, as symbolized by Ottawa’s decision to approve the sale of Nexen to a Chinese state-owned enterprise but at the same time to put in place guidelines to limit future investments.”

Paul Evans notes that the Chinese were upset by the mixed signals they received over the investment decision and Cabinet’s failure to ratify the FIPA for almost two years. Since then, economic interest has been expressed in small steps forward, but the full promise of a bilateral strategic partnership was never achieved. Meanwhile, Canadian public attention has been preoccupied by allegations of Chinese cyber hacking, expansion in the South China Sea, and the arrest of Canadian missionaries in China.

Major analysts of the Canada-China relationship such as Wendy Dobson, Paul Evans and David Mulroney, are critical, by varying degrees, of Canada’s reluctance to engage politically with China even while seeking closer economic relations. Evans attributes it to Canadian assumptions that their perceptions of freedom, democracy, human rights, and rule of law are built on universal values “that are as good for China as they are for Canada.” For the Harper government, engagement came to mean advancing a commercial agenda and a moral enterprise intended to affect China’s internal social and political order.

From the very first, Canada’s engagement with the PRC was built on the belief that closer ties would help to ameliorate differences, build convergences and better integrate China into the community of nations. Recognition of China’s Communist government through the One China Policy in 1970, support for China’s inclusion in the World Trade Organization in 2001, the 2005 Strategic Partnership, and various agreements on tourism, financial information services, science and technology, air services, nuclear cooperation and the environment are just a few examples of overtures intended to make China seem less alien. And while such engagements by Canada and other G-7 allies have made China more familiar, they have not succeeded in transforming China into a compliant, Western-style democracy.

China is extending its global, economic, and military capacities to gain hegemonic status in Southeast Asia and to negotiate a new global balance of power with the United States. It is no longer a question of socializing China to behave like the West but recognizing that, in the absence of a global traffic cop, each government will, as Ian Bremmer and Nouriel Roubini put it, “work to build domestic security and prosperity to fit its own unique political, economic, geographic, cultural, and historical circumstances.”

Evans and Mulroney are in broad agreement that Canada should accept China as it is, not as Canadians wish it to be. Evans observes, “China is neither a friend nor an enemy, neither an ally or an adversary. But it can be a good partner.”Mulroney argues that China is neither the sum of all fears nor the answer to all prayers. The question for Canada is whether to turn away from this global iconoclast or find new ways to engage – not to convert but to gain the knowledge necessary to effectively promote regional

stability and to become more prosperous at the same time.

China’s leaders freely admit that there is a certain amount of trial and error involved in their diplomatic relations with the world. China’s outreach follows a broad general direction but not a predetermined path. It responds to signals from the outside and seeks convergence between its own unique practices and the norms of international institutions. The government of China might not know in advance how to reach the final objective, but it is confident in its eventual success. “China in many ways epitomised the gradual and pragmatic approach to reform. Its process has been described as ‘crossing the river by feeling stones.’”

China will continue to make territorial claims in areas it considers to be in its natural sphere of influence. It will aggressively seek markets and resources it considers necessary for its economic wellbeing and it will continue to utilize mechanisms that challenge international norms to gain information and technological advantage. While specific security recommendations are beyond the scope of this paper, it is clear that attempting to isolate economics from politics has not worked in the past. As Dobson and Evans argue, “Canada’s future prosperity depends on more societal, commercial, and educational interaction with China” within a policy framework that addresses the tensions of the shifting balance of power in the Asian region.

Canadian Attitudes Towards China

Canadians’ negative perceptions of China are fed by media accounts of unsafe products, unfair labour standards, and violations of cyber security and intellectual property rights. Meanwhile, the experiences of Canadian companies actually doing business in China refute much of the negativity and reveal a promising and profitable market.

For example, the Asia Pacific Foundation’s 2014 survey of Canadian businesses operating in China found that perception and reality are misaligned on intellectual property rights (IPR) violations. More than 70 percent of Canadian companies in China report that they have not experienced any violations within the past five years. Some 64 percent of firms operating in China report their business as profitable or very profitable and 83 percent of firms plan to expand their business.

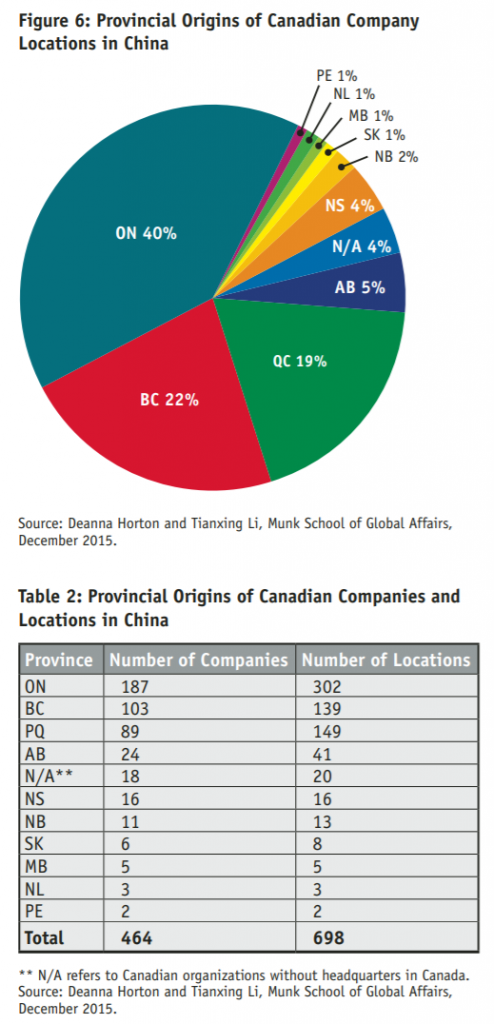

Brands are important. Fifty-two percent of business owners believe that having a recognized Canadian brand helps business development in China. But, perhaps the most important factor is staying power. More than 80 percent of businesses that have been in China for more than ten years rank their business as profitable. This need for staying power is also confirmed by the experiences of businesses from other countries. According to research from the University of Toronto, 40 percent of Canadian company locations in China are from Ontario, 22 percent from BC and 19 percent from Quebec (see Figure 6 below). Note that the pie chart reflects the number of locations of Canadian companies, not individual companies. Nevertheless, the proportions are approximately the same, whether referring to locations or companies (see Table 2).

China is Not for the Timid or the Ill-prepared

Doing business with China is not without challenges. Among the problems reported by Canadian businesses, 64 percent complained about an unclear and inconsistent regulatory environment.

Differing or inconsistently applied regulatory standards will be a challenge for Canadian exporters, particularly in the food sector, underscoring the need for a comprehensive trade strategy that includes not just market access but firm commitments on regulatory cooperation. The Canada-China Business Council identifies a number of challenges facing Canadian exporters including shipping storage requirements for seafood, bans on certain food additives such as ractopamine in pork, labelling requirements imposed by local governments and sanitary and phytosanitary standards that are not always in line with international standards.

While business operations in emerging markets such as China can be highly profitable, entrepreneurs must be able to do what it takes to stay in the market long enough to profit. Goldfarb notes that businesses with a track-record of success, access to financing, and high levels of innovation are better able to penetrate fast-growing markets and generate much higher profit levels than could be achieved at home.

The lack of a strong business push to engage with China has helped to feed the Canadian government’s policy ambivalence. As Derek Burney and Fen Hampson note, Canadians live in a “North American cocoon,” lulled into complacency by proximity to the U.S. market.

Trade with the United States is easy but the opportunities for Canada are shrinking as the United States diversifies to more efficient suppliers from other parts of the world. Even China is now competing against Canada in the United States. This was starkly demonstrated by Bombardier’s loss of a US$566 million contract to build new subway cars for Boston to the China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation.

China is a consumption-based economy, energized by new players and new products but Canadian firms need a push to get involved. Canada’s exports to China in 2014 amounted to just over $14 for every member of the Chinese population while Canada’s exports to the United States worked out to about $1260 per American. Chinese demand for imports of pork has grown so large that Manitoba producers are sending hundreds of live animals by cargo plane between Winnipeg and Chengdu.

An aggressive trade strategy with China requires not only government action but also changes to Canadian business culture. As Wendy Dobson notes, “Canada comes and goes but it does not stay.” Without a sustained Canadian presence, it will be impossible to build demand for Canada’s iconic brands and services. Canadians must consider trade with China as an opportunity for the economy fifty years from now, an economy that may look very different from Canada’s resource-intensive economy of today.

Small Steps Forward

Incremental but important steps have been made between China and Canada. While not enough to embed a pattern of cooperation, they are sufficient to prove that formal arrangements yield rewards. For instance, in June 2015, China announced a market access deal for British Columbia blueberries that could be worth up to $65 million. While this is excellent news for blueberry growers on Canada’s west coast, the same cannot be said of other Canadian industries that still lack preferential access to this giant consumer market.

FIPA

The Canada and China Foreign Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement came into force in October 2014, offering both material and symbolic support for closer bilateral relations. The FIPA grants investors access to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), providing a level of security for investors who make large investments in other countries, and ensuring legal recourse against discriminatory and arbitrary practices such as expropriation.

The primary benefit of Canada’s FIPA with China is to provide stronger protection for Canadian investors in China. International trade lawyer and former Canadian trade negotiator, Matthew Kronby, argues that the value of such agreements is to define improper behavior by governments in order to create a more stable and predictable investment environment. “The benefits are particularly valuable in countries like China where the rule of law is not assured.” Kronby also notes that Canadian fears of a flood of arbitration claims from China as a result of the FIPA are unfounded. To date, China has launched only a handful of claims globally despite the ability to do so through various legal agreements.

Government officials who are aware of their liability are less likely to act capriciously and unfairly. Sarah Kutulakos, executive director of the Canada-China Business Council, notes that the very existence of the FIPA helps to rein in bad behavior by China’s sub-national governments against Canadian investors. This restraint, she explains, is because the government in Beijing does not want to lose face defending questionable actions by a provincial or city government in an international arbitration.

Contrary to concerns voiced by some Canadians about China’s acquisition of Canadian commodity assets, the FIPA does not in any way grant China preferential access to Canadian resources nor does it determine who can invest in Canada or in what sector. Chinese and all other global investors remain subject to all domestic rules governing proposed acquisitions, as set out in the Investment Canada Act.

RMB HUB

Another positive indication of Canadian interest in China is the establishment of a renminbi 65 trading hub in Toronto – the first ever in the Americas – on March 23, 2015. The trading hub allows businesses to convert Chinese RMB to Canadian dollars without having to first convert the funds into an intermediary currency (usually U.S. dollars). The Canadian Chamber of Commerce estimates the hub could boost Canada’s exports to China by as much as $32 billion over the next decade.

The RMB hub is an excellent example of what can be achieved through business and government collaboration and political leadership. The initiative had political momentum because its announcement coincided with Prime Minister Harper’s 2014 visit to China, but the announcement represented the culmination of months of exchanges between Beijing, Ottawa, Vancouver and Toronto. Private sector interests such as the Toronto Financial Services Alliance, AdvantageBC, the Canada-China Business Council, and trade and finance officials recognized the opportunity that China was providing, and did the consultation, coordination and planning necessary to turn opportunity into action.

Faster and more secure RMB conversions allow Canadian exporters to save on exchange costs and the ability to pay in Chinese currency makes it easier for Chinese importers to buy from Canada. Since it is presently quite difficult to move currency in and out of China, the RMB hub is even more valuable. This may not be the case in a few years when China further liberalizes its financial system so Canadian businesses should be encouraged to make use of the RMB hub now.

Other Sources of Activism

The provinces have been a source of momentum when progress with China has stalled at the federal level. Provincial participation keeps federal efforts on task in areas of provincial authority, such as natural resources and services and regionally specific exports such as canola, pork, seafood, potash and coal. Provinces are active participants in trade missions – a 2014 Council of Federations mission to China included Ontario, Quebec and PEI – and many have their own trade-promotion offices in China.

Federally organized Team Canada visits are also useful because they help to coordinate and focus often-disparate business and government initiatives. (The Canada-China Business Council reports several instances of a number of Canadian “official” groups visiting the same area of China at the same time without any apparent knowledge of each other’s presence, much to the surprise of the Chinese hosts.) Team Canada missions provide a focal point for Canadian activities but they are not a substitute for the institutionalized structures of cooperation that provide predicable and transparent rules.

Trajectory of China’s Trade Policy and the Agreement with Australia

As China’s economic clout grows, its trade and investment ties have extended around the world.68 China is now a global exporter of capital, skilled workers, and services. These relationships have made the Chinese government more open to economic agreements with large and advanced economies.

China’s WTO accession in 2001 demanded much in terms of domestic policy reform, liberalization and new transparency commitments. Consequently, even though China pursued a number of regional free trade agreements immediately after accession, its capacity to go deeper than its WTO commitments was limited. As Razeen Sally notes, China’s post-Uruguay Round FTAs were “trade light”, often motivated more by foreign policy than by commercial considerations.

The commitments offered to Australia in ChAFTA, however, are indicative of a change in China’s ability to go well beyond the WTO in its new preferential trade agreements. While Australia has gained a temporary advantage by being one of the first countries to benefit from these deeper commitments, Canada can also capitalize on China’s new openness. China does not have an FTA with any country in North America and, in the western hemisphere, it has only signed FTAs with Costa Rica and Chile (both agreements could be considered “trade-light”). There is strategic value to Canada being the first North American nation to sign an FTA with China.

ChAFTA also provides a template for what Canada can achieve. Canada and Australia are similar economies in terms of size and development. The concessions Australia extracted from China are a benchmark to guide Canadian negotiators. By the same token, Australia is also a competitor to Canada in key sectors so Canada’s overall competitiveness is hurt by its second-mover status. Nevertheless, when it comes to preferential access to the world’s largest consumer market, being the second mover globally, 72 and the first mover in North America is an opportunity that Canada cannot afford to miss.

China is positioning itself as the cornerstone of the Asian market. One of China’s main external initiatives has been the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The AIIB is a financial institution focused on infrastructure development in the Asia-Pacific region. Spearheaded by China, the AIIB is supported by 37 regional and 20 non-regional members. As of July 2015, 51 states had signed the Articles of Agreement to establish the bank. The AIIB is open to expanding both its regional and non-regional membership. Canada, Japan and the United States are the only major world economies not to seek membership, (Australia is a member of the AIIB). Not only does Canada’s absence from AIIB deny it the opportunity to help guide Chinese decision making on infrastructure investment, it denies Canada’s infrastructure service providers the inside track on billions of dollars’ worth of procurement in the engineering and construction industries.

Canada should reconsider its refusal to join the AIIB. It should also find ways to participate in other Chinese infrastructure activities such as the One Belt One Road Initiative (Silk Road Economic Belt) that is building trade and infrastructure linkages between China and Eurasia.

Canada’s completion of the TPP negotiations in October 2015 is a positive step towards more productive engagement with Asia. It provides access to important Asian markets, particularly Japan. It situates Canada as a central participant in a coordinated and transparent trading arrangement. It helps set common rules and understandings to reduce transaction costs caused by regulatory barriers, and seeks to provide solutions to new challenges that emerging markets have brought to the global trading system. These include disciplines on the behavior of stateowned enterprises, provisions to guarantee cross-border data flows while protecting personal privacy, and measures to help mitigate the use of currency manipulation as trade protectionism. While these latter interventions are limited in the TPP and still untested, they are an important first step upon which to build more robust rules in the future.

China is not a part of the TPP but it has made no secret of following the negotiations carefully and adopting many of the new negotiating subjects in its Regional Cooperation Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations with the ASEAN states. Rather than a mechanism to isolate China, the TPP could encourage China to deepen and expand its liberalization and transparency commitments with a view to one day joining the TPP or formally linking the RCEP with the TPP.

The United States is moving ahead on a number of fronts to create closer economic ties with China. These include a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) that will help United States investors meet, and in some areas exceed, the protections that Canadian investors have through the FIPA. The U.S. and China are also working together on bilateral initiatives in the areas of technology and subfederal procurement. Because of the integration between the United States and Canada, Canada derives secondary benefits from any agreement between China and the United States But, doing a deal with China first would mean that Canada would have a longer period to become accustomed to China trade norms and would be able to tailor an agreement to the specific characteristics of the Canadian economy, similar to the advantages Canada generated by negotiating a free trade agreement with the European Union ahead of the United States.

The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement: Results and Lessons for Canada

While Canada has been delaying on deeper trade with China, Australia signed an FTA in June 2015 after almost 10 years of negotiations. ChAFTA is the most comprehensive FTA China has ever signed and will be worth an estimated AU$18 billion to the Australian economy over the next decade. While Australia is primed to take advantage of its first-mover status, Canada needs to make sure that it is next in line.

CHAFTA HIGHLIGHTS

ChAFTA is the first truly comprehensive trade deal China has signed with a developed country and contains “best-ever” Chinese commitments in a number of sectors. Australia already has a more robust trading relationship with China than does Canada. Total two-way trade between Australia and China was estimated at AU$150 billion in 2013 while Canada-China two-way trade was pegged at only CA$73 billion the same year.

One of ChAFTA’s unusual elements is the services chapter in which Australia uses a NAFTA-style negative-list approach while China uses a a GATS-style positive list. Negativelist approaches identify only what is excluded from the agreement while a positive list itemizes everything that is included. Positive-list agreements tend to include fewer trading areas and do not deepen trade as much as negative-list agreements. So, in the services deal struck between China and Australia, the latter provided more inclusive liberalization. Nevertheless, despite retaining the positive list, China opened up more services sectors to Australia than it has in the past.

AGRICULTURE

Once it is fully implemented (11 years after entry into force), ChAFTA will eliminate 95 percent of all tariffs. All tariffs on Australian wine, meat and seafood, currently between 10 and 25 percent, will be eliminated within 4

years. Tariffs on barley and sorghum will be eliminated on entry into force. (Canadian barley, meanwhile, will continue to face a 3 percent tariff in China.)

Market access for beef is quota-limited: 170,000 tonnes for the first 4 years, gradually increasing to a little over 200,000 tonnes after 10 years. There are no restrictions on market access for pork or seafood. Australia will also benefit from an exclusive duty-free quota on wool.

Certain agricultural sectors such as canola oil and vegetable oils are excluded from ChAFTA because they are designated “significantly sensitive staples” by China. Rice and sugar are also excluded.

NATURAL RESOURCES

Upon full implementation of the agreement, 99 percent of Australia’s resources, energy and manufacturing exports will enter China duty-free. This includes tariffs of 3 percent on coking coal to be removed on entry into force and 6 percent on thermal coal to be eliminated after two years. Tariffs up to 10 percent will be eliminated for refined copper and alloys, aluminum oxide, zinc, aluminum, nickel and titanium dioxide, many on entry into force. Tariffs of up to 10 percent on pharmaceuticals, including vitamins and health products, will be eliminated either immediately or within four years.

SERVICES

China has gone beyond its GATS commitments in a number of areas but many fall short of full liberalization. For example, China has agreed to allow wholly owned Australian hospitals, but only in four provinces and three cities. However, Australian service suppliers will be able to establish for-profit aged care institutions throughout China. In tourism, Australian services suppliers will be able to construct, renovate and operate wholly Australian-owned hotels and restaurants in China.

China has committed to allow Australian companies to provide manufacturing services. ChAFTA also allows Australian suppliers to provide technical consulting and field services in coal bed methane and shale gas extraction. China has guaranteed access for consulting related to oil and gas resources (in cooperation with Chinese partners).

Labour mobility also makes significant strides in ChAFTA. New Investment Facilitation Arrangements (IFAs) will operate under the framework of the Australian visa system. These will allow certain Chinese-owned companies that invest in Australian infrastructure projects above AU$150 million to negotiate labour market access flexibilities.

In architecture and urban planning, Australian firms will be allowed to obtain more expansive business licenses to undertake higher-value projects in China.

Both sides have committed to expand their education services relationship. Australia and China signed an MOU aimed at improving recognition of qualifications and promoting exchange opportunities. Although the Australian government is making much of the commitments in ChAFTA on education, the only firm Chinese commitment is the listing of 77 Australian providers on the Chinese Ministry of Education website. According to Australian government sources, 88 percent of Chinese students studying in Australia in 2013 chose to study at institutions listed on the website. China has agreed to ongoing discussions about adding new Australian schools to the site.

FINANCIAL SERVICES

Australian banks are well positioned as a result of ChAFTA to benefit from new market opportunities. China has committed to deliver improved access to Australian financial service providers in the banking, insurance, funds management, securities, securitization and futures sectors. ChAFTA also designates an official RMB clearing bank in Sydney allowing trading of Chinese currency in Australia. The allocation of an RMB 50 billion quota will allow Australian-domiciled fund managers to purchase equities and bonds directly from China’s mainland securities exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen. (These commitments are nearly identical to what Canada negotiated through the RMB hub.)

Australian banks will enjoy much greater access to the Chinese market. China has agreed to reduce the waiting period for Australian banks to engage in RMB-denominated business from three years to one year. China will remove the two-year profit-making requirement as a precondition to providing local currency services. Australian bank subsidiaries in China are the only foreign bank subsidiaries to enjoy an FTA commitment guaranteeing their eligibility to engage in the credit asset securitization business.

For the insurance sector, China will allow Australian insurance providers access to China’s statutory third-party liability motor vehicle insurance market, without local establishment or equity restrictions.

For the first time in an FTA, China has agreed to allow Australian financial service providers to establish joint venture futures companies with up to 49 percent Australian ownership and extend national treatment to Australian financial institutions for approved securitization business in China. Australian securities firms in China will benefit from new commitments, raising foreign equity limits to 49 percent (above China’s WTO commitment of 33 percent) for participation in underwriting domestic ‘A’ and ‘B’ shares as well as ‘H’ shares (listed in Hong Kong), and guaranteeing the ability to conduct domestic securities funds management business.

It is important to note that while Canada has a few large financial services companies with an established track record in China, the benefits that Australia is getting through the ChAFTA are in line with what Canada needs in order to build the competitiveness of its incumbent firms and bring new firms into the market.

FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI)

Australia has also made significant FDI concessions, raising the screening thresholds for private Chinese investments in non-sensitive sectors to AU$1,094 million from AU$252 million. This is on par with thresholds for Chinese private investment in Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and the United States. However, all investments must originate from China to qualify for the higher threshold, and not come from offshore accounts. Foreign investment in residential real estate is excluded from ChAFTA.

STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES (SOES)

ChAFTA does not eliminate mechanisms already put in place by the Government of Australia to review investment by Chinese SOEs. Although Australia has liberalized the screening threshold at which private Chinese investments in non-sensitive sectors are considered by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), Australia retains the right to screen Chinese investments at lower thresholds for agricultural land, agribusiness, and sensitive sectors. Furthermore, all investment by Chinese SOEs will be subject to review, regardless of transaction size. The FIRB will often consider factors such as whether investors operate at arm’s length and on a commercial basis when it applies the national interest test. In Australia, there is no real definition of what is necessary to pass the national interest test, and the FIRB does not need to disclose how it arrives at a particular conclusion.

In Canada, SOE investment rules are fairly similar to Australia. Under the Investment Canada Act, all SOEs must meet the net-benefit test. An SOE is defined as an enterprise that is owned, controlled or influenced, directly or indirectly by a foreign government. When assessing whether such acquisitions are of net benefit to Canada, the Minister will examine whether the SOE adheres to Canadian standards of corporate governance including commitments to transparency and disclosure, independent members of the board of directors, independent audit committees and equitable treatment of shareholders. The Minister will assess the effect of the investment on the level and nature of economic activity in Canada, including the effect on employment, production and capital levels in Canada. Like Australia, Canada has a fairly opaque process of foreign investment review.

SHORTCOMINGS AND UNCERTAINTIES

While Australia’s agreement with China created a great deal of new market access, Australian negotiators were unable to generate Chinese concessions in sugar, rice, cotton, wheat, maize, or canola. While Australia obtained a market access quota for its important wool industry, it was not able to negotiate reduced tariffs for wool. Milk powder and beef are also subject to quota limits under special safeguards.

Although investor-state dispute settlement is becoming more widespread in trade and investment agreements, the right of Chinese firms to sue Australian governments for policy changes that adversely affect their interests leaves Australians wary. Another provision that could attract public criticism is the right of Chinese investors who invest over AU$150 million to bring in temporary migrant workers to Australia without local labour market testing. Australia retains the right to screen Chinese investment but the threshold has quadrupled to just over AU$1 billion. Chinese investment is excluded from sectors deemed sensitive by Australia such as agriculture, media, telecoms and defence.

Benefits to Australia

Manufactured Goods and Pharmaceuticals

- Manufactured products, such as electronics and appliances: phase out of 5 percent tariff on Chinese products (lowering costs for Australian consumers) and phase out of 3-14 percent tariff on Australian products.

- Pharmaceuticals, including vitamins and health products: elimination of tariffs up to 10 percent, either immediately on entry into force or within 4 years.

Agriculture

- Dairy: tariffs up to 20 percent eliminated within 4 to 11 years.

- Beef: tariffs of 12 to 25 percent eliminated over 9 years.

- Wine: tariffs of 14 to 20 percent eliminated over 4 years.

- Wool: a new Australia-only duty free quota, in addition to continued access to China’s WTO quota.

- Sheep, pork, live animals, hides, skins and leather, horticulture, and seafood: phased elimination of tariffs of up to 30 percent.

- Processed foods such as canned fruit, orange juice, and natural honey: tariff reductions or elimination.

Resources, Energy and Manufacturing

- Coal, aluminum and gemstones: phase out or elimination of 3 – 10 percent tariffs.

- Iron ore, gold, crude petroleum oils and liquefied natural gas (LNG): ChAFTA locks in existing zero tariffs.

- Coking coal: tariffs of 3 percent eliminated on entry into force.

- Thermal coal: tariffs of 6 percent eliminated over 2 years.

- Refined copper and alloys (unwrought), aluminium oxide (alumina), unwrought zinc, unwrought aluminium, unwrought nickel and titanium dioxide: tariffs of up to 10 percent eliminated, many on entry into force.

Services

- Legal services: Guaranteed market access for Australian law firms to establish commercial associations with Chinese law firms in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ).

- Education services: Within one year of entry into force, China will list on the Ministry of Education website 77 Australian private higher education institutions.

- Telecommunications services: Guaranteed market access for Australian companies investing in specified value-added telecommunications services in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ).

- Financial services: China has committed to deliver new or improved market access to Australian financial services providers in the banking, insurance, funds management, securities, securitization, and futures sectors.

- Tourism and travel-related services: China has guaranteed that Australian services suppliers will be able to construct, renovate and operate wholly Australian-owned hotels and restaurants in China.

- Health and aged care services: China will permit Australian service suppliers to establish profit making aged care institutions throughout China, and wholly Australian-owned hospitals in certain provinces.

- Agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing services: Australian businesses will be allowed to own a majority share in joint ventures providing these services in in China.

Investment

Investment review: Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board will continue to screen all investment by Chinese state-owned enterprises.

Investor-state dispute settlement: Australian firms will have some rights to sue Chinese governments for policy changes that adversely affect their interests.

Joint ventures: Improved access to partnerships with Chinese firms for legal and financial services in China, but 49 percent Australian ownership limit on financial services joint-ventures.

Implications and Opportunities for Canada

ChAFTA contains a number of benefits and opportunities for Australian sectors that compete with Canada. Direct competitors include meat, wine, seafood, resource products, (especially coal), manufactured goods, education, healthcare and tourism.

In the short term, this means that Australian companies will have a competitive advantage over Canadian firms until Canada achieves similar market access commitments. There is, however, some advantage to the fact that Australia has negotiated a deal with China before Canada. While ChAFTA may have taken the Australians ten years to negotiate, Canada may benefit from a speedier process because of the principles and practices that agreement put in place.

Now that Australia has made significant strides to open China to trade liberalization with the West, Canada may be able to meet or exceed the benefits of the Australia deal. A possible silver lining is China’s exclusion from the ChAFTA of wood pulp and canola. These exclusions could preserve market access for two of Canada’s most important exports, if China decides to open these sectors later.

GOODS MARKET ACCESS

Canada competes directly with Australia in the beef and pork sectors where Canada faces tariffs of between 14 and 20 percent. Gradual removal of tariffs under ChAFTA provides a clear advantage to the Australian industry. But there are opportunities for Canada as well, especially when it comes to seafood.

Canadian seafood exports to China increased by 16.2 percent between 2012 and 2013.95 Overall, China is Canada’s second most important destination for fish and seafood exports and it was Canada’s third largest export source in 2013, accounting for nearly 8 percent of all shipments.96 Canada is the sixth largest exporter of seafood to China, well ahead of Australia, which is not even in the top ten.

Sugar, rice, cotton and wheat are excluded from ChAFTA. Sugar and wheat are important sectors for Canada but China has designated them as “sensitive sectors.”

Wood and paper products were also excluded from ChAFTA because they are “sensitive to China’s economy or culture.”98 Canada is currently challenging China at the WTO99 in response to duties on Canadian wood pulp. Its willingness to face a WTO challenge underscores China’s commitment to protect the domestic industry and it is unlikely to give away much in an FTA. This is a significant challenge for Canada since pulp and paper exports to China are currently estimated at $2.7 billion.

A Canada-China agreement might put greater pressure on Canada to continue to open Canada’s protected dairy sector – a domestic reform process accelerated by the CETA and TPP negotiations. Even though China is not a dairy exporter and will not be pressuring Canada to lower tariffs on Chinese dairy products, one of the preconditions to maintaining supply management is that Canada not export most dairy products. China, meanwhile, has a large and growing demand for dairy products. As long as Canadian producers are shackled to supply management, they will be unable to tap into this valuable export market.

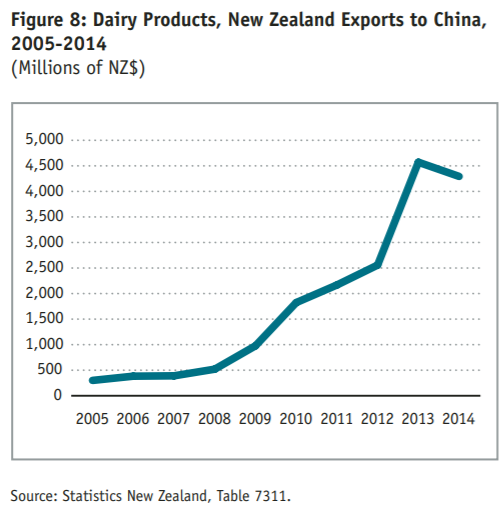

Some Canadian dairy companies are already banking on the value of trade with China. In March 2014, Montreal-based Saputo Inc. bought Australia’s Everyday Cheese for $134 million.103 This gives Saputo an increased presence in the Australian market and it is likely they will prosper from the dairy concessions made in ChAFTA. Evidence of China’s growing demand for dairy can be seen in the sharp rise in dairy shipments from New Zealand to China (see Figure 8 below).

Other sectors may also find incredible opportunities with increased trade with China. Unlike Australia, Canada has a well-established aerospace industry. China is building and improving airports all over the country. To meet demand and move people from city to city China requires an expanded fleet of aircraft, especially regional aircraft. Aircraft manufacturers have predicted that China will require an additional 5,300 aircraft over the next 20 years. Canadian companies such as Bombardier are well positioned to take advantage of such an opportunity, especially for the C-series regional aircraft.

China’s aviation boom also requires a significant increase in trained personnel. Canada’s CAE is well placed to provide pilot training to the thousands of new pilots China is estimated to require and CAE has a number of training programs already in place.

SERVICES

China’s infrastructure development is key for Canadian service providers, especially in engineering and construction. China is building at an exceptional rate and has a number of massive undertakings requiring a level of skill and knowledge that must be imported. For example, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has approved plans for the construction of the country’s first rail links to Laos and Myanmar. The Dali-Ruili railway in Yunnan province is already under construction and is set to run 335 kms over rugged terrain, 75 percent of which is slated to be bridges and tunnels.105 The line includes the 30 km long Gaoligong Mountain Rail Tunnel, the longest of its kind in Asia. Projects of this sort provide incredible opportunities for Canadian companies from construction to engineering and consulting services.

As China continues to build its rail network, it will need to purchase railcars to service regional routes. An FTA with China would help place Canadian companies on an even footing with Chinese companies to build railways and railcars.

To keep up with Chinese urbanization, China requires inter-city rail links as well as light rail for inner city transportation (a fairly untapped market). Bombardier is currently an important rail equipment supplier in China with a number of joint-ventures in operation. Foreign suppliers continue to have difficulties accessing China’s government procurement market. A focus on procurement liberalization should be a major element of Canada’s trade strategy with China.

The transportation sector is supported by services, including financial services, which Australia has managed to negotiate access for. Similar access for Canada’s financial services sector would be one of the largest beneficiaries in an FTA with China. The ability to finance and insure some of the large infrastructure projects in China would be a welcome development for many Canadian institutions looking to expand their market share in China.

Some of the concessions that Australia has received in financial services simply brings them up to the level where Canadian companies are already operating. Companies such as Manulife benefit from a long-standing relationship doing business in China and are able to own more than 49 percent interest in a joint venture (JV) due to grandfathering arrangements. China is slowly relaxing their JV ownership requirements on pension and investment managers. But, Australian financial institutions have also been granted new access that Canadian banking and insurance companies, both incumbents and potential new entrants, could benefit from.

Chinese concessions in extractive sector services are an important gain for Australia but they also create opportunities for Canada. Having the same access as Australia to the Chinese market would permit Canadian consultants in oil and gas to get a foothold in this most important Asian market. Given China’s demonstrated interest in Canadian natural resources, Canada has leverage to obtain even better commitments in the energy services sector.

China is Canada’s largest export market for education services, valued at over $1.8 billion. Considering the limited commitments in ChAFTA regarding education, Canada has an opportunity to promote its institutions as a destination for Chinese students. It is unlikely that Canada needs an FTA to get a similar commitment to Australia’s, (i.e. listing approved institutions on a government website) so Canada should be lobbying to achieve parity with Australia as soon as possible. However, an FTA could provide Canadian education providers with even more substantive access than Australia enjoys.

INVESTMENT

Canada ranks 36 out of 43 in OECD surveys of regulatory restrictiveness perceptions by investors. Canada’s restrictions on Chinese SOEs are reportedly creating a chilling effect on Chinese investment in Canada. The final ChAFTA deal maintains similar restrictions on investment by SOEs in Australia as Canada currently holds. Canada may consider taking a more liberal approach to its SOE rules in order to allow for greater levels of SOE investment under controlled conditions, especially if loosening restrictions helps Canada gain access to sectors that were formerly closed.

DISPUTE SETTLEMENT

ChAFTA contains an Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanism, but carve outs including the right to regulate in the public interest remain as a safeguard. This is very similar to what currently exists in the Canada-China FIPA.

Economic Analysis of a Prospective Canada-China FTA (CCFTA)

While there has been no quantitative assessment of a Canada-China FTA to date, assessments of China’s actual and prospective FTAs with other trading partners indicate that the gains are large for most small and medium trading countries. China is an appealing trading partner because China is a large economy and has relatively high tariffs and a comparatively restrictive domestic policy regime for services and investment. Thus its liberalization agreements could offer substantive benefits to countries like Canada whose economies are already liberalized and in conformity with global trade norms.

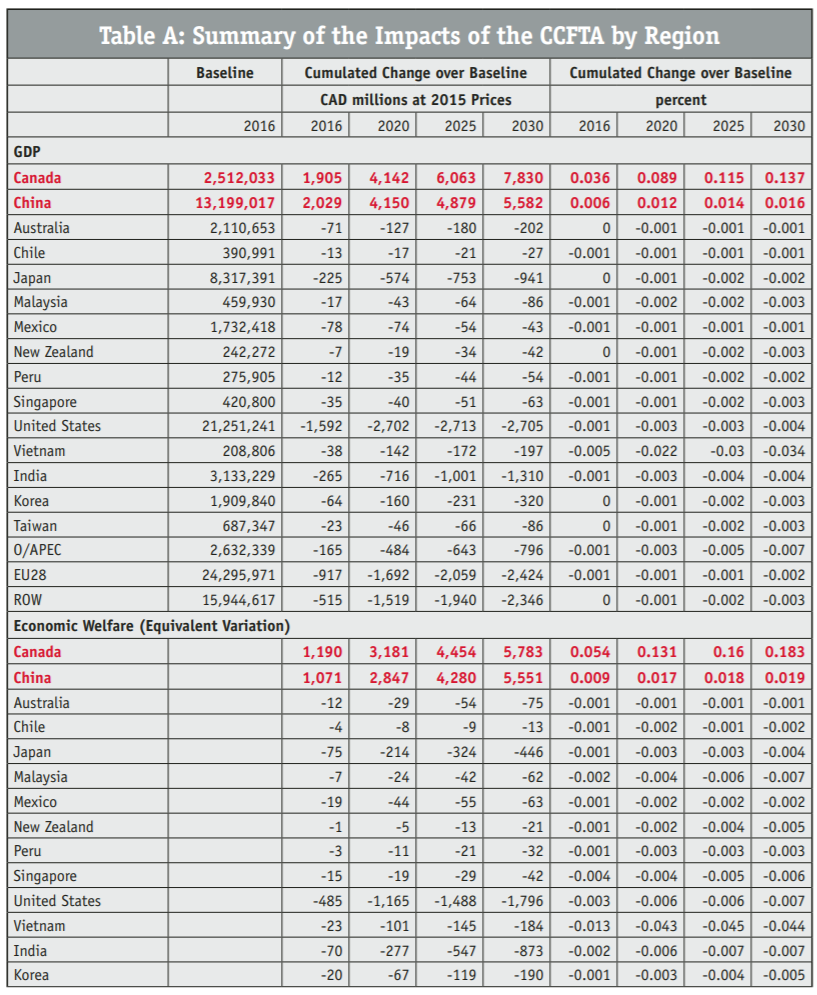

To analyse the impact of a potential Canada-China FTA on tariff rates for goods, we employ an adapted version of the GTAP computable general equilibrium modelling framework, using the results of China-Australia Free Trade Agreement in 33 sectors to estimate the likely outcome for an agreement with Canada (see Tables A, B, and C in Annex 1). Not only is ChAFTA the most recent agreement that China has negotiated, Australia is an economy very similar in size and composition to Canada’s. Services outcomes of ChAFTA are evaluated against the OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index. The GTAP-FDI model used for the analysis allows us to identify potential investment impacts. Conservative estimates are employed throughout the analysis, thus the results may understate the impacts by as much as 50 percent. What analytical models will not capture are the benefits that are difficult to quantify such as goodwill, technology transfer, and increased mutual awareness.

RESULTS

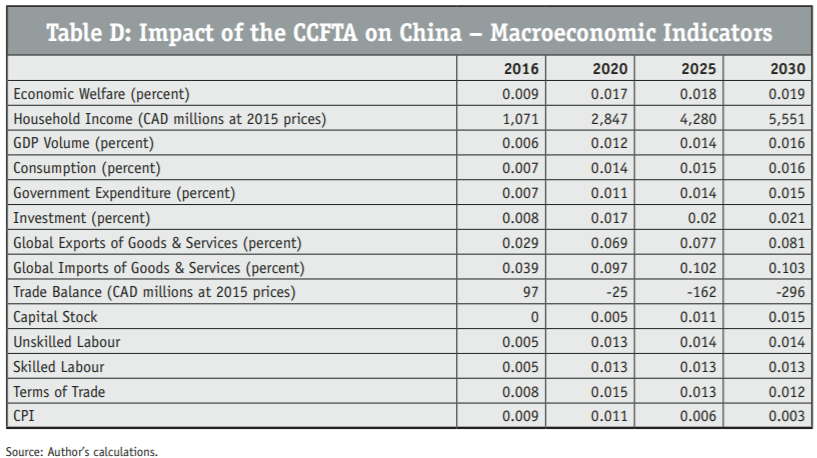

For Canada, a free trade agreement with China would result in about $7.8 billion in increased GDP by 2030 in value terms (taking into account both quantity and price changes), a boost of about 0.14 percent in real terms (see Table A). The comparable gains for China are about $5.6 billion or about 0.02 percent over the same period – comparable to Canada in absolute terms, but much smaller in relative terms given the difference in economic size of the two parties (see Table D).

As a result of Canada’s preferential trading status with China, the agreement would divert trade away from other countries. The United States will be hardest hit. A CCFTA would cost the United States approximately $2.7 billion in GDP by 2030 (see Table A). However, another way of looking at trade diversion losses for the United States are as a mechanism to reduce Canada’s dependence on U.S. markets and a way to share the preferences accorded to the United States under NAFTA.

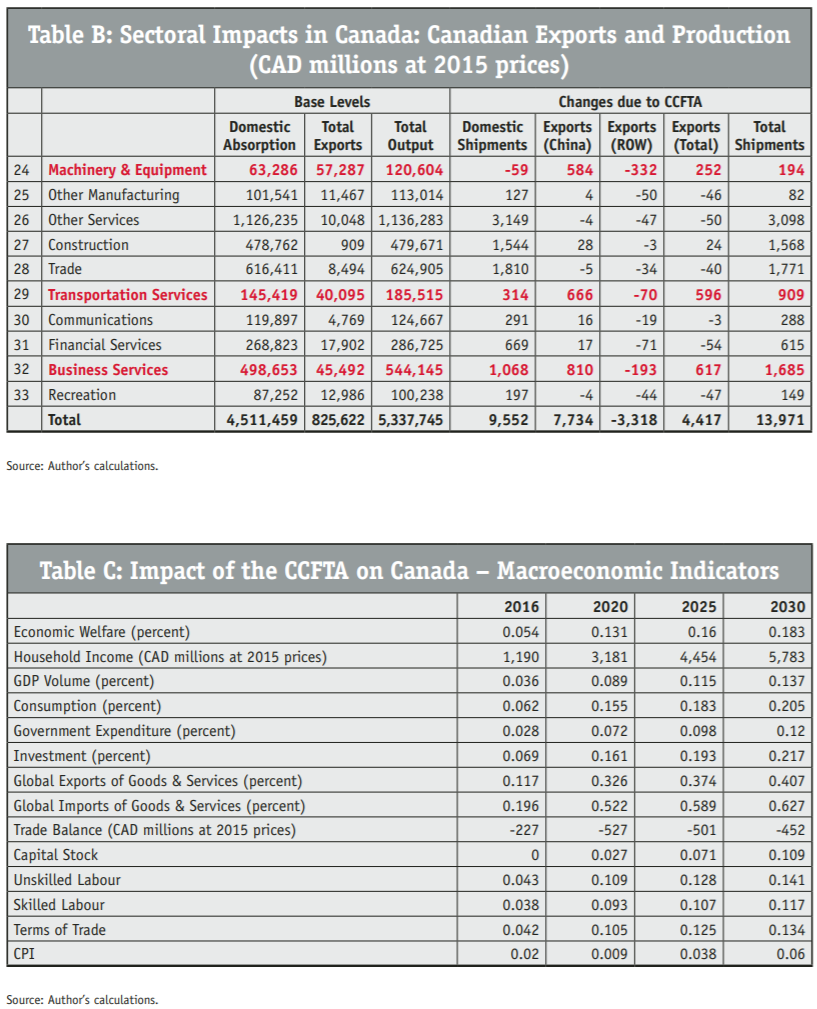

Economic gains are measured not just in new export sales opportunities but also in lower-priced imports for consumers and as inputs for manufacturing. The combined effect results in an estimated increase of $5.7 billion to Canadian household income by 2030 (see Table C). The economic activity will result in greater FDI in Canada: the increase in the foreign-owned capital stock in Canada would amount to 0.11 percent or $982 million in 2030.

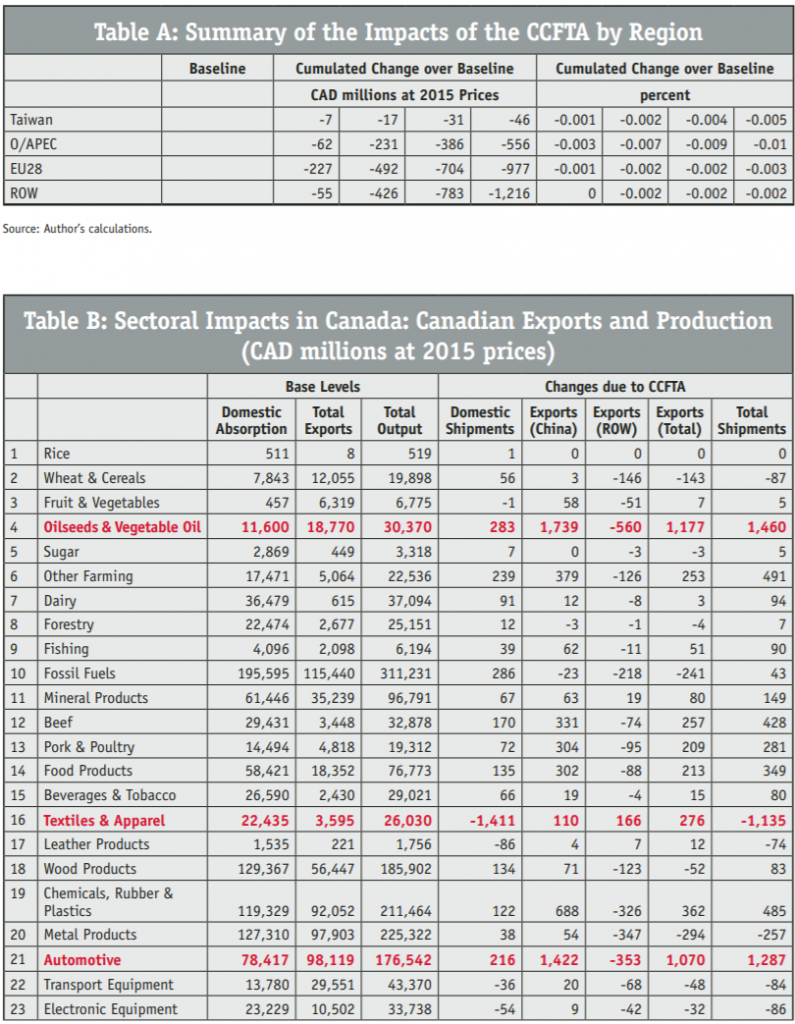

SECTORAL EFFECTS

By 2030, Canada’s overall exports to China are projected to grow by $7.7 billion annually and total shipments (which includes domestic sales as well as exports to third parties) by $10.4 billion.115 At the sectoral level, we estimate that automotive exports to China will increase by more than $1.4 billion annually, chemicals/rubber/plastics by some $688 million, machinery and equipment by $584 million, and approximately $1.7 billion more per year in exports of oil seeds and vegetable oil (see Table B).

Turning to the import market impacts for Canada, total imports from China would rise by $7.4 billion. However, taking into account the trade diversion implied by the preferential nature of the CCFTA, the total import expansion is on the order of $5.08 billion. In other words, about $2.68 billion of the additional imports from China will result from Canadian importers switching to Chinese suppliers given the improved market access the latter would enjoy under the CCFTA.

OTHER EFFECTS

Preferential rules of origin (ROOs) increase the administrative cost of trade transactions, reducing the gains that could be made without such costs (e.g. the multilateral WTO regime is not segmented by regional preferences). Since willingness and ability to comply with origin rules in order to utilize maximum trade benefits varies from agreement to agreement and business to business, it is difficult to say exactly how business would respond to the CCFTA, not to mention how vigorously the authorities on both sides would enforce the rules. The costs of using preferences in an Asia Pacific trade context are likely to be higher, and therefore preference utilization lower, than in a NAFTA context, simply because of the additional logistical steps, including for example potential trans-shipment of Canada-China trade through Hong Kong or U.S. ports.

As a general guideline, primary products that are easily traded in bulk and do not require complex documentation, such as agri-foods, would have a rate of preference utilization of around 100 percent while more sophisticated industrial products would have a utilization rate of around 60 percent. (In other words, the more complicated the compliance documentation, the less likely that business will make use of them.)

Without a preferential trade agreement, traders default to the most favored nation (MFN) rates agreed to under the WTO. China’s average applied MFN rate in 2013 was 9.4 percent, and Canada’s 2014 rate was 6 percent. Even with preference utilization of, say, 60 to 80 percent, Canadian exporters still stand to make substantial gains in a bilateral deal with China.

Such trade gains will help to drive productive activity in Canada. The GDP gains of $7.8 billion are achieved by reallocating capital and labour across sectors in response to the changed market incentives as well as by stimulating additional capital investment (part of which flows in from abroad in the form of increased FDI).

Employment is also expected to increase as a result of increased demand and the additional economic activity stimulated by the CCFTA, which should generate higher wages. In our simulations, the capital stock and labour inputs both increase by about 0.1 percent. This amounts to about 25,000 additional jobs in Canada across all skill levels.

The expansion of economic activity generates increases in wages (0.14 percent for unskilled labour and 0.12 percent for skilled labour) and returns to capital (about 0.15 percent). As the smaller partner, the impact on Canadian wages and investment is greater than the impact on China’s, resulting in a fairly strong increase of Canadian export prices relative to import prices (i.e., an improved “terms of trade”). From an economic welfare116 perspective, Canada achieves part of the gains from the CCFTA in the form of more economic activity and part of it in the form of higher returns to labour and capital.

The Path Forward

Australia has shown that a meaningful trade deal with China can be negotiated. Because of this more aggressive trade strategy, Australian companies will now have an advantage in almost every area in which they compete with Canada (natural resources, agriculture, and financial services). For Canada, there are opportunities in key sectors and from the overall trade facilitation and transparency benefits of an agreement as a whole.

Canada has a unique and time-limited opportunity to pursue liberalized trade and market access with China. The signing of ChAFTA may inspire other countries, such as the United States, to move ahead with an agreement. Canada needs to re-focus its China strategy on trade opportunities. As a relatively small market, Canada must be nimble, moving ahead of larger competitors to gain preferential access, as was accomplished with the CETA, completed prior to the U.S. TTIP.

As Dobson argues, in the short-term, an FTA with China may help close Canada’s trade deficit by selling more natural resources. In the long-term, the objective should be to diversify bilateral trade, with Canada exporting more knowledge-based goods that China cannot produce and by building Canadian advantages in industries such as transportation and infrastructure. An FTA should not focus on the economy of Canada today, but rather what we hope it will look like in 50 years.

A future-oriented policy means that industries that are not core to the Canadian economy today need to be considered for their future growth potential. Clean technology is perhaps the best example. While Chinese cities suffer from stifling levels of pollution, traffic jams, and the need for energy, Canadian know-how in this industry can create benefits for years to come. In 2012, the revenues from the Canadian clean technology industry amounted to $11.3 billion. At the current growth rate it is expected that this industry will be worth $28 billion by 2022.

The Chinese government has taken steps towards promoting environmental protection by enacting a series of laws to increase the accountability of polluters and increasing public disclosure. As part of its new legal framework, China has created incentives for clean technology, providing tax breaks and fiscal assistance to encourage reduction of emissions. While relying on exports of natural resources is good trade strategy for Canada in the short term, green technology exports will help Canada make up lost ground in China and build capacity to become a global clean technology leader.

Conclusions

The first priority of a Canada-China economic strategy is to re-invigorate the commitment articulated in the 2012 Complementarities report for a Canada-China free trade agreement. Not only will an agreement give Canada the market access advantages it desperately needs, it will also provide a rules-based framework to help offset asymmetrical power dynamics resulting from China’s size. In commercial relations between large countries and smaller ones, smaller countries like Canada always benefit from enhanced rules as a substitute for economic weight.

As Canada’s economy faces slowdowns due to declining energy prices and slow-growth trading partners, it must look further afield for stimulus. Chinese officials have stated that they are open to negotiate with Canada. New leadership promises to reinvigorate Canada’s international relationships on all fronts. For Canada, there is no better time to begin crafting an economic engagement strategy that will serve Canadian interests for the next several decades.

Recommendations

Immediately

- Operationalize the commitments to create the Economic and Financial Strategic Dialogue and Foreign Affairs Ministers Dialogue.

Within 12 Months

- Create a strategic economic and political framework that is both specific enough to guide immediate action and flexible enough to accommodate bilateral, regional and global change for their future growth potential. This should begin with a re-evaluation and updating of the 2012 Complementarities study.

- Launch negotiations for a bilateral trade liberalization agreement with China. In addition to market access gains, an agreement will build a framework of rules and common understanding that will help to increase transparency and decrease risk for Canadian manufacturers, service suppliers and investors.

- Encourage Canadian businesses to expand their use of the RMB hub through education, promotion and sharing of success stories.

Within 18 Months

- Join the AIIB. This will bring Canada into a productive venue to understand and possibly influence China’s intra- and inter-regional development plans and help position Canadian suppliers to take advantage of Chinese infrastructure spending.

- In tandem with AIIB membership, become more involved in China’s One Belt One Road economic initiative.

- Re-invigorate the Asia Pacific Gateway and Corridor Initiative beyond Western Canadian transportation projects to link up with and enhance multimodal transportation links to the east, north, and south.

- Eliminate the opacity from the net benefits test for investment by state-owned enterprises, focusing instead on vigilant enforcement of Canadian labour, environmental and related rules by all enterprises, regardless of the investor’s origin.

- Launch a bilateral green technology project to link together sustainable energy and environment objectives (such as water conservation in energy production).

- Add Canada’s institutions to China’s list of recommended universities.

- Support China’s eventual TPP inclusion with a view toward long-term inclusion in a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific.

Annex 1: Tabular Data

References