Canada’s trade with Mexico: Where we’ve been, where we’re going and why it matters

Introduction

By 2030, Mexico is likely to be the world’s 8th largest economy. As an engine of growth and a platform for North America’s global competitiveness, Mexico provides Canadian businesses with the cost and demand advantages of an emerging market but with the lower risk afforded by two decades of integrated trade rules and practices. Canadians have been slow to recognize the opportunities Mexico provides and government policy towards Mexico has sent mixed messages. Canada’s linkages to Mexico through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) give us an advantage, but we must invest in the relationship today to reap future gains. This report examines the development of, and prospects for, the Canada-Mexico economic relationship and identifies key areas for future action.

Overview of the Current Relationship

Mexico and Canada, 1994 to 2014

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Mexico faced the challenges of a troubled and volatile economy characterized by:

- inefficient state controls over key areas of the economy;

- a public treasury dependent on oil rents that had been battered by oil

price volatility; - debt and monetary crisis;

- poverty and income inequality;

- uncompetitive and insulated domestic industries; and

- lack of investor confidence.

The Mexican government responded with an ambitious slate of domestic reforms matched with an outward-oriented economic policy that included membership in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and closer economic ties with the United States. These actions and financial guarantees by the U.S. helped to calm international lenders and stabilize the peso. Mexico also gained secure, preferential market access for its nascent export industry through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Canada’s own economic stimulus activities of the 1980s included reduction of protectionist trade barriers to expose Canadian industries to increased international competition, and expanded access to its largest trading partner through the 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA). By the mid-1990s, Canada had made the transition to more open trade and was reaping the benefits. Between 1987 and 1996, Canada’s Gross National Product (GNP) increased by 33 per cent and exports as a share of GNP increased from 23 per cent to 33 per cent. Exports more than doubled during this period and, indicative of growing North American supply chains, so did imports. Canada’s share of direct investment abroad increased during this period from $11 billion to $37 billion, another sign that Canadian firms were maturing and seeking new markets and lower-cost production opportunities across national borders.

The composition of Canadian exports was also changing; the relative share of manufacturing and raw commodities declined as the share of knowledge-intensive goods and services increased. Within the manufacturing sector, the growth areas were those that required higher levels of specialization such as industrial and agricultural machinery and aircraft.

With more than 80 per cent of Canadian exports bound for the U.S., there was little Canadian interest in the Mexican market.5 Moreover, Canadian officials worried that adding Mexico to the CUSFTA would erode Canada’s preferential access to the U.S. and distract American officials from issues of concern to Canada. Nevertheless, U.S. officials made it clear that stabilizing their southern neighbour was a priority and they would go ahead with a Mexican free trade deal with or without Canada. Canadian officials realized that if the U.S. had duty-free access to both Canada and Mexico, and Canada had access to only one, this could divert external investment away from Canada (a ‘hub and spoke’ scenario). Thus, as a defensive action, Canada became a somewhat reluctant convert to NAFTA.

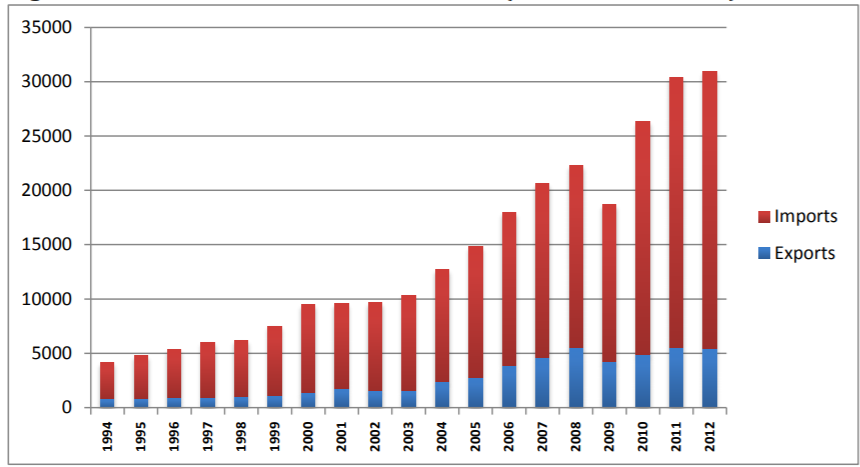

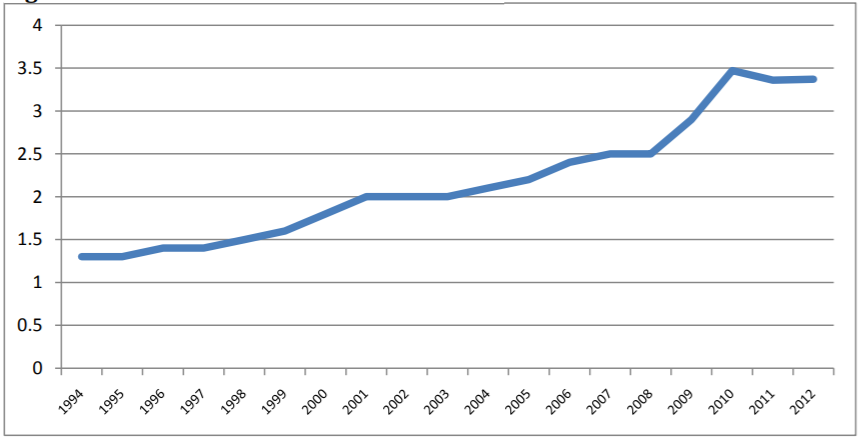

Figure 1: Canada’s Goods Trade With Mexico (millions of US dollars)

Although trade with the U.S. has continued to dominate the relationship, looking back from the present day, few would dispute that Canada-Mexico trade grew more as a result of NAFTA than it would have otherwise (see Figure 1). NAFTA jumpstarted the relationship by providing:

- Preferential access through reduced or eliminated tariffs;

- Compatible regimes for standards and technical barriers; and

- Reduced risk through transparent dispute settlement mechanisms.

NAFTA’s integrative forces stimulated the growth of cross-border supply chains in sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and agri-food. It generated opportunities for the export of services such as financial, energy, and information and communications technology (ICT), and it reduced risk for Canadian investors in sectors such as banking and mining.

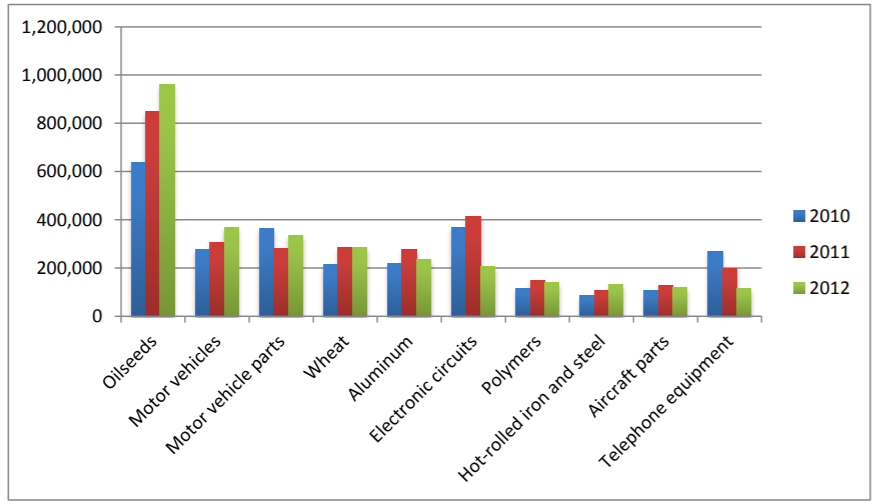

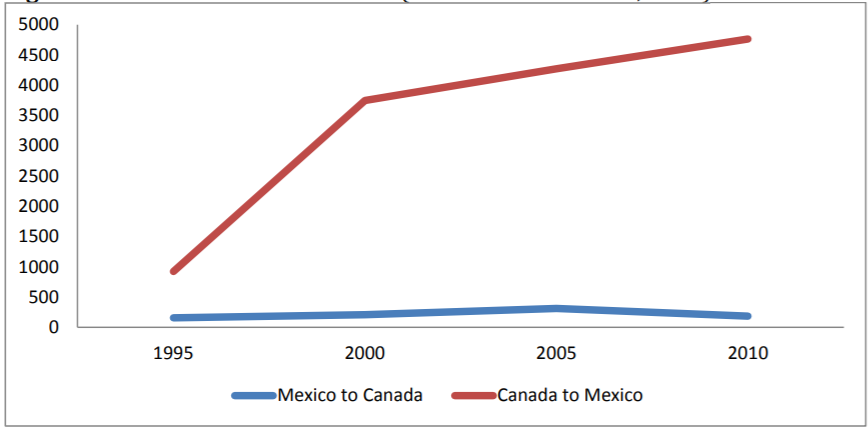

Figure 2: Canada’s exports to Mexico (thousands of U.S. dollars)

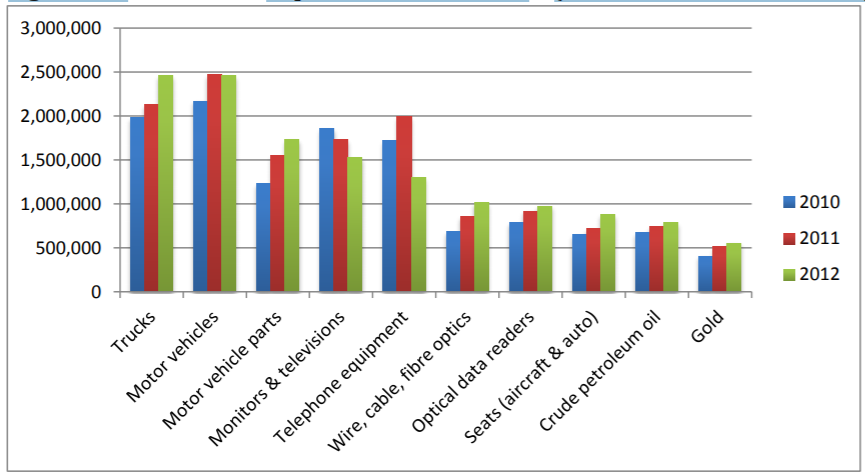

Figure 3: Canada’s imports from Mexico (thousands of U.S. dollars)

The value of NAFTA as a platform for North America’s global competitiveness is difficult to conceptualize without a clear picture of supply-chain dynamics. Very few products are wholly produced in one country and wholly consumed in another. Production is disaggregated within a regional market to maximize comparative advantage. For Canada, such advantages include expertise and capital. For Mexico, they include affordable skilled labour and proximity to markets. Moreover, the production cycle includes not only extraction, harvesting or manufacturing tasks, but also many types of affiliated services, from accounting to transportation.

Supply chains provide an economic ecosystem in which the survival of the whole depends on the health of the parts. A Canadian firm’s decision to move an assembly job to Mexico is not a net loss for Canada if Mexican assembly activity supports highvalue engineering jobs in Canada and creates higher returns for Canadian investors. To continue to enjoy the benefits of high-value-added activities in innovative and technological fields, Canadian firms must be embedded in supply chains that include lower-value-added assembly and service activities, even if those activities take place in Mexico or the U.S.

Although there is insufficient data on the precise levels of Canadian content in Mexican products, Mexican exports to the U.S. include an average of 40 per cent U.S. content and Canadian exports to the U.S. contain an average of 25 per cent U.S. content.6 It stands to reason, then, that many U.S. exports to Mexico contain Canadian content while many U.S. exports to Canada contain Mexican content.

Figure 4: Canada’s Trade with Mexico as % of Canada`s Global Trade

Even though Canada-Mexico trade and investment increased after NAFTA (see Figures 4 and 5), there is very little commercial activity between Canada and Mexico that does not also include the U.S. Even after the 2009 financial crisis made it plain that the U.S. economy had entered a period of stagnation, Canadians seemed more interested in the far-off and more uncertain prospects of China, India and Brazil – economies characterized by high growth and large populations but also formidable market access barriers.

Why have Canadian business and policy leaders failed to engage in a meaningful way with Mexico? Are we overlooking important opportunities due to outdated perceptions of the Mexican market? Are our diplomatic relations effectively supporting our business interests? This report will examine Canada’s business opportunities in Mexico and evaluate prospects for re-engagement.

Trade

NAFTA put Mexico on a path to economic modernization and helped to provide investors with the certainty and transparency required for growth. The increasingly outward-looking orientation of its industrial sector has resulted in a permanent restructuring of the economy.

Twenty years after NAFTA, Mexico is the largest exporter and importer in Latin America. It exports more manufactured goods than all other Latin American countries combined. The country remains highly dependent on exports to the U.S., but it is on a path toward diversification. Between 2006 and 2013 exports to the U.S. as a percentage of total Mexican exports dropped from 88 per cent to 80 per cent. In 2012, Mexico was Canada’s fifth-largest export destination after the U.S., China, the United Kingdom and Japan, and Canada’s third-largest source of imports after the U.S. and China.

Geographic proximity sets Mexico apart from its most threatening competitor, China. A container leaving Shanghai takes around 31 days to reach New Jersey; a similar container from Veracruz takes five days. Shorter distances and rising energy (transportation) prices mean that Mexico is a cost-effective alternative to China for both Canada and the U.S.

Today, Mexico has 12 free trade agreements (FTAs) involving 44 countries on three continents, providing preferential access to a potential world market of more than one billion consumers and investors. Mexico (together with Canada) entered the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations in 2012 and its FTA with the European Union took effect in 2000.

Since both Canada and Mexico are TPP negotiating parties and both already have a trade deal with the EU, Mexico’s leaders have made repeated requests to their NAFTA partners to harmonize policies and negotiating positions on matters of joint interest, particularly on rules of origin, standards and technical barriers.

Both Canada and Mexico have an interest in ensuring that new commitments do not erode NAFTA advantages. Only Mexico, however, has come out front in demanding that NAFTA partners do not “shoot ourselves in the foot” by granting advantages to other countries that they deny each other. Canada’s Minister of International Trade is more sanguine, indicating that the upgrading effects that the TPP will have on NAFTA are more or less a fait accompli.

Investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico has been driven by the opportunity to export to the U.S. Two-way investment between Mexico and the U.S. has surged to more than six times the 1993 level. While the value of U.S. FDI is still much greater than investment in the opposite direction, Mexican FDI in the U.S. is growing quickly. Mexican companies have become leaders in diverse areas of the U.S. market such as cement, baked goods and dairy. Mexican firms have also invested heavily in U.S. media, mining, beverages, and retail stores.

Figure 5: Direct Investment Abroad (millions of U.S. dollars; stock)

Two-way investment between Mexico and Canada is much weaker (see Figure 5). Canada has strong investment in a few sectors including banking, mining and aerospace, but even though the stock of Canadian investment runs between $4 and $5 billion per year, Canada’s investment presence lacks diversification. Mexico’s investment in Canada is very small with the annual stock hovering around $200 million. However, the success of a number of Mexican firms in the U.S. market bodes well for expansion into Canada as well. Mexico is a small but growing foreign investor and FDI growth in Canada has been stunted as Mexican business leaders feel unwelcome because of the ‘temporary’ visa imposed on Mexican nationals in 2009 (discussed later in this report).

FDI is key if Mexico’s economic development is to continue. While NAFTA boosted Mexican growth and prosperity by locking in reforms, Jorge Castañeda, who served as Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs in the early 2000s, argues that the agreement did not contribute sufficiently to the development of the upstream industries that provide materials for assembly further along in the production cycle. In 1994, 73 per cent of Mexico’s exports were composed of imported inputs. By 2013, that number rose to 75 per cent. As well, with one million Mexicans entering the workforce every year, competing for an average of 35,000 new jobs, wages

remain flat and pressure to seek jobs outside of Mexico continues. Mexican growth requires that its productive capacity expand and diversify beyond basic assembly.

NAFTA helped to lock in sound macroeconomic policies that led to stable public finances, low inflation, a stable currency, and a more transparent business environment. Nonetheless, Castañeda asserts that new investment is blocked by what was omitted from the NAFTA agenda, namely labour mobility, infrastructure development and foreign investment to update the energy sector.

Diplomatic relations

Unlike the agreements underpinning the European Union, NAFTA did not establish strong institutions for managing and strengthening the economic integration of the three countries. The three partners did set up a number of NAFTA working groups, but most of them have fallen into disuse, and meetings among leaders and ministers to take stock of the relationship and plan future cooperation are rare.

Occasionally new trilateral initiatives emerge to respond to new issues. Examples include the Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP), which was created to help balance trade and security priorities within a post-9/11 environment, and the North American Competitiveness Council, which was formed to provide private sector input into the SPP.14 The challenge for these institutions and their successors is how to provide continuing relevance to businesses and stakeholders so that they can withstand ebbs in political attention.

Most recently, there has been a trend towards managing the relationship through dual bilateral initiatives with the U.S. For example, Mexico and Canada each have bilateral regulatory and border agreements with the U.S., but not with each other. There also is a Mexico-U.S. CEO Forum and a High-Level Economic Dialogue of cabinet-level decision makers. Canada is not included in either of these.

Outside of the economic sphere, Canada and Mexico cooperate in a variety of security, diplomatic, social and health initiatives, such as joint action on the H1N1 influenza outbreak. Canada provides technical assistance to Mexico in the areas of policing, defense and intelligence-gathering.

The Canada-Mexico Partnership (CMP), an annual meeting of officials chaired at the assistant deputy minister level, has existed since 1994. Members of the private sector are invited to participate in working groups that deal with agri-business, human capital, trade, investment and innovation, energy, environment and forestry, labour mobility, and housing and sustainable communities. While the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) claims the CMP is “the key mechanism for bilateral cooperation”, the DFATD website makes no mention of the 2013 CMP meeting in Mexico City.

NAFTA achieved moderate gains in providing labour mobility for business visitors and intra-company transferees. For example, companies such as Linamar, Bombardier and Scotiabank (see below) send significant numbers of technical and managerial professionals for short-term assignments at Mexican affiliates.

Also, Canada, through its Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), has been more successful than the U.S. in providing opportunities for Mexican skilled labour to work on a temporary basis in occupations with demonstrated labour shortages. In 2012, more than 20,000 Mexican workers came to Canada using the TFWP and related programs.

NAFTA has been less successful in providing mutual recognition of skills and certifications in regulated professions (welders, electricians, and nurses). Only a handful of professions – such as accounting, architecture and engineering – have managed to establish full mutual recognition. Streamlined mobility through mutual recognition of credentials (supported where appropriate by joint education programs) will help to enhance the efficient integration of Canada-Mexico supply chains.

Businesses are key to trilateral progress. Some of the notable initiatives include the informal alliance of the U.S. Business Roundtable, the Canadian Council of Chief Executives and the Consejo Mexicano de Hombres de Negocios. The North American Forum also convenes an annual meeting of thought leaders from business, government and academia. At the bilateral level, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce in Mexico and its counterpart organization in Canada provide a front-line point of contact for businesses interested in trade and investment activities.

However, there are no trilateral or Mexico-Canada organizations or think tanks that have as their core mandate the enhancement of the economic relationship. In the absence of focused information, research, and convening resources, ad hoc efforts may keep the relationship afloat but will not contribute to its growth.

Challenges to the relationship

Despite growth opportunities, the three biggest challenges to the Canada-Mexico relationship are federal policy ambivalence – some of which may be attributed to competition for U.S. influence – Canada’s over-reaching visa requirement for Mexican nationals, and the largely erroneous perception of unmanageable security threats to Canadians doing business in Mexico.

The double edge of U.S. influence

With its insistence on a trilateral trade pact, the U.S. brought Mexico and Canada closer together but it may also have prevented the two countries from developing natural ties independent of U.S. influence. Competition for U.S. attention on trade and economic issues has prevented Mexico and Canada from sharing resources and exerting joint leverage to counter the U.S. on matters of joint interest.

Canada and Mexico both have bilateral border, regulatory and energy initiatives with the U.S., but Mexico and Canada rarely talk to each other directly on such issues. Moreover, because Mexico has proven capable of attracting more Congressional interest, Canada’s bilateral initiatives run the risk of losing governmental resources, profile and (ultimately) longevity.

Business apathy has also been a drag on the relationship. Canadian business has not been motivated to engage strongly with Mexico because the U.S. market has traditionally provided a ready source of demand. The fact that U.S. demand growth is now weaker underscores the need for diversification, particularly toward emerging markets. Canada, however, is not well equipped to take advantage of new opportunities. Andrea Mandel-Campbell argues that protectionist policies for key industries, combined with easy access to U.S. markets, have bred complacency and hobbled Canada’s competitiveness. Meanwhile, the paucity of internationally recognized Canadian brands ensures that Mexican investors are similarly disinterested in Canada. “When it comes to the rest of the world, Canadians are armchair travelers, rarely roused from the familiar contours of the ‘intramestic’ American market.”

Visas

There is broad consensus in both Canada and Mexico that it is important to know who is entering one’s country and to be able to screen for security threats. Nevertheless, Canada’s imposition of a complex and intrusive “temporary” visa that has lasted for more than five years is perceived as an insult to Mexican leaders and has chilled relations with Canada. Mexico’s Ambassador to Canada, Francisco Suarez, says Canada has the most stringent visa system for Mexicans of any country in the world. Mexicans wishing to come to Canada as tourists or business visitors are probed about their family and financial histories. Says one Mexican businessman who has cut off all travel to Canada: “How do I know that the bank statement I give Canada won’t find its way into the hands of thieves or extortionists who might threaten my family?”

In 2009 Citizenship and Immigration Canada implemented the visa requirement to deter bogus refugee claimants from Mexico. A similar visa requirement was imposed on citizens of the Czech Republic. The Czech visa was removed in 2013 but the Mexican visa remains in place, even though the federal government added Mexico to the list of “safe” nations deemed unlikely to produce legitimate asylum claimants more than a year ago.

Canada has paid a high price for the visa in terms of reputation and lost revenue from tourists, students, and investors. In 2008, Mexican tourists spent $365 million in Canada. In 2012, that number fell below $200 million. Canadian airlines have had to eliminate or reduce planned routes and it is virtually impossible for a Mexican to arrange to travel to Canada on short notice, whether for business purposes or to take advantage of Canada’s competitive airfares to Asia.

Many Mexicans believe that the Harper government gave them the false impression that the visa would be removed once Canada revised its refugee determination process. Mexico and Canada are unlikely to be able to reinvigorate their diplomatic and investment relationships until the visa is modified or removed.

Security

Security issues related to narcotics cartels are among the major challenges facing Mexico. Although the past decade has seen Mexican federal, state, and municipal governments attempt to tackle the problem, the paradox of rooting out organized crime is that confrontation creates more violence, at least in the short term. When power relations among criminal organizations are destabilized, criminal activity diversifies away from narco-trafficking toward robberies, kidnapping and other forms of violence. According to the UN, Mexico’s homicide rates have more than doubled since 2006.

Organized crime in Mexico also benefits from relatively low levels of reporting by citizens, corruption among officials, and a lack of legitimate economic opportunities for unskilled workers. Border regions, especially in the south, are particularly affected. Migrants from Central America tend to exacerbate Mexico’s security challenges. However, street violence in Mexico City and other major economiccentres is rare during daylight hours. Canadians who are currently working in Mexico advise that a business visitor will have no difficulty moving from place to place. Those wishing to establish more permanent business activities in Mexico should engage the services of a security consultant and seek out reliable local business partners.

Of the more than 2400 Canadian affiliates with investments in Mexico, most are located in the more secure regions of the country. Mexican crime statistics suggest that the safest states are Campeche, Querétaro, Hidalgo and Yucatan; the most insecure states are Chihuahua, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulípas, and Coahuila.

Canadian mining companies operating in rural areas of Mexico where few legitimate economic opportunities exist are particular targets for kidnapping and extortion, but they can mitigate the risks with professional security measures. Senior executives employed by companies that are perceived to be wealthy may also be targets for kidnapping and extortion.

Short-term remedies for Mexico’s security problems are unlikely. Continued vigilance by the government, together with investment in education and poverty alleviation, will assist in the longer term. Canada can contribute to Mexican stability by continuing to provide training for police, judicial and border officials, and by collaborating on perimeter security. For most Canadian business professionals, the bottom line is that most areas of Mexico are safe places to do business as long as they take reasonable precautions.

Deepening the Bilateral Relationship

Mexico as the Engine of Growth for North America

The Mexican economy has changed from a troubled, inward-oriented developing economy to an engine of growth for North America. It is the second-largest economy in Latin America with a per capita GDP well above those of other Latin American countries. While worldwide growth has slowed following the 2009 financial crisis, IMF data shows Mexico’s recent GDP growth rates to be about one-third higher than Canada’s.

With a population of 117 million, Mexico has about three times as many people as Canada but a nominal GDP that is similar: US$1.8 trillion for Canada, $1.2 trillion for Mexico. Mexico’s GDP is actually greater in purchasing power parity terms, making it the 11th largest economy in the world by that measure. Economists predict that by 2030, Mexico will be the world’s 8th largest economy and Canada the 16th. The global economy of 2030 will be led by emerging economies and only the U.S. and Japan will remain among the largest economies. By 2050, less than eight per cent of global trade will take place in North America, compared to 15 per cent today.

Mexico’s growth prospects are supported by reforms that contribute to social stability. A predictable and outward-oriented market enhances Mexico’s appeal to investors and exporters, and poverty alleviation efforts help expand the base of Mexican consumers who might purchase Canadian products. Between 2000 and 2010, Mexico’s middle class increased from 35 per cent of the population to 39 per cent.

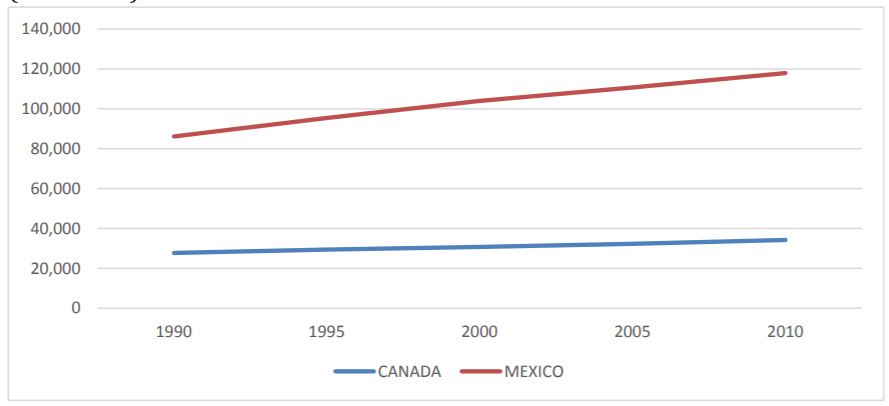

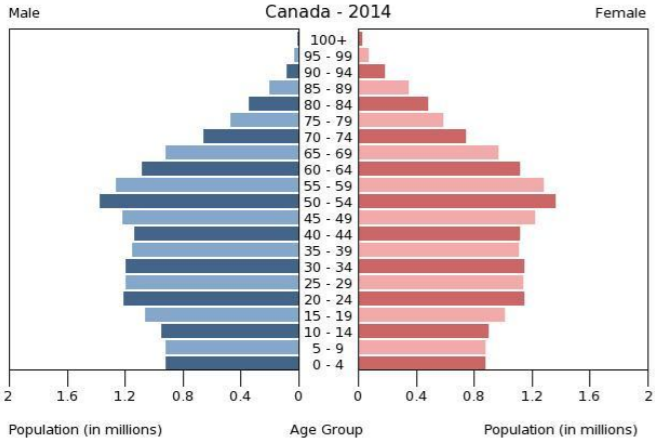

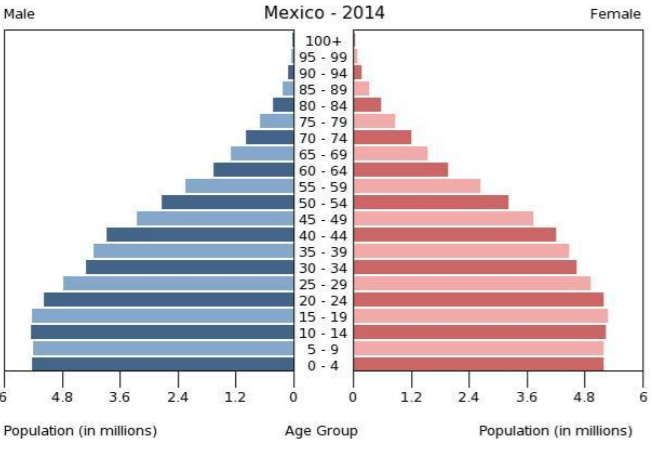

Demographic trends also contribute to Mexico’s economic prospects. Its population is growing (see Figure 6) and youthful (see Figure 7), in marked contrast to Canada’s relatively flat population growth and relatively high number of people who are retired or soon will retire from the workforce. The International Labour Organization estimates that Mexico’s economically active workforce will rise by 20 per cent between 2010 and 2020.

Figure 6: Population Growth Trends, Canada and Mexico 1990-2010

(Thousands)

Figure 7: Canada and Mexico Age/Population Distribution

Mexico also has the highest annual growth rate of secondary school graduates in the OECD. Fifty per cent of students currently attending school are expected to complete secondary education and 20 per cent are expected to complete post-secondary education – approximately double the share of graduates 20 years ago. While still below the OECD average, post-secondary attainment levels are higher than those of Austria, Brazil, Italy and Turkey. Education reforms now underway are aimed at increasing the quality of education and expanding the number of skilled workers.

Complementarity with Canada

Globalization and the transformation of manufacturing contribute to the growing complementarity of the Canadian and Mexican economies. The disaggregation of production and offshoring trends of the 1990s saw lower-skilled assembly jobs move to lower-wage locations. Mexico benefited from this trend at first, but the emergence of China and markets with even lower wages, such as Cambodia and Laos, meant that companies did not remain in Mexico long if their primary motivation for relocating was to gain access to inexpensive labour. However, the tide is now turning. Chinese wages have been rising quickly and are now about 20 per cent higher than Mexico’s on average. As a result, some manufacturers are returning to Mexico. In the process, they benefit from Mexican know-how and proximity to both U.S. and Latin American markets.

Similarly, the Canadian economy has changed. The U.S. share of Canadian goods and services exports has declined from 87 per cent in 2000 to 72 per cent today. Since 2005, Canada’s outward foreign direct investment has exceeded its inward flows – a strong indicator that Canadian firms are looking for opportunities elsewhere and are moving certain activities to lower-cost or higher-demand markets.

Since 2000, Canada’s share of global manufactured goods exports has declined by half. Some of this is attributable to exchange rates and a generalized shift in economic activity from manufacturing to resources and services. At the same time, Canadian firms have been slow to adapt to changing patterns of global demand and have shown insufficient focus on high-growth emerging markets. Former Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney has argued that Canada’s underperformance is “more a reflection of who we traded with than how effectively we did it.”

China and India, while potentially profitable, carry more risk and are more expensive to service than Mexico. In a U.S. study comparing manufacturing opportunities in Mexico and China, the Wilson Center (2013) found that Mexican production is more cost-effective for:

- products that are more expensive to transport, such as motor vehicles and large electronics;

- quality-intensive precision instruments such as medical supplies or specialized components that are inputs for other products;

- specialty products that are made in small batches; and

- customized products, especially those requiring just-in-time delivery.

The greatest advantages for Canadian firms are Mexico’s skilled but relatively lowcost workforce, mature clusters in key sectors, access to international markets facilitated by preferential trade agreements, and integration in both North American and Latin American supply chains.

Despite a slow start to the relationship, resources are available to Canadian firms wishing to explore Mexican opportunities. Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service, as well as Export Development Canada and the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta provide commercial advice and representation for Canadians seeking opportunities in Mexico. The Canada-Mexico Chamber of Commerce is an important source of advice. Proméxico, the trade and investment promotion agency of the Mexican government, provides detailed sectoral and market information and will assist with introductions and sectoral outreach missions.

Commercial opportunities for Canadian firms

A handful of Canadian firms were early converts to the opportunities presented by Mexico. These flagship firms offer important lessons in how relationship-building, flexibility, and perseverance yield profits in Mexico.

Scotiabank

Scotiabank has been active in Mexico since 1967, maintaining a presence even when economic turmoil and rapid shifts between nationalization and privatization caused other foreign banks to flee during the 1980s and 1990s. During this period, Scotiabank became a national player in Mexico’s financial sector by acquiring a majority share of Grupo Financiero Inverlat (now Scotiabank Inverlat). As the seventh largest bank in Mexico, Scotiabank has played a key role in financing the operations of Canadian enterprises in Mexico, and has helped to provide loans and mortgages to Mexico’s middle-income earners during times when credit was scarce. While other Canadian banks have a presence in Mexico, only Scotiabank is involved in both commercial and personal banking. Scotiabank now has operations throughout the hemisphere and more than a fifth of its total profits come from international operations.

Bombardier

Bombardier has been doing business in Mexico since 1981, when it sold 180 subway cars to Mexico City. Anticipating the market-access opportunities offered by NAFTA, Bombardier Chairman Laurent Beaudoin acquired a nearly bankrupt Mexican train car manufacturer in 1992. Considerable investment and upgrading were required to create world-class manufacturing capacity. From its base in Hidalgo, Bombardier Transportation now supplies most of Mexico’s passenger rail requirements and, making use of NAFTA and Mexico’s other preferential agreements, it exports train cars, parts, and locomotives to Canada, Australia, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. The plant employs about 2,000 skilled workers. Bombardier Transportation will expand significantly if the company wins a bid to manufacture trains for Mexico’s planned $9 billion investment in three new railway projects.

Building on the company’s successes in rail, Bombardier’s aerospace division established a $200 million manufacturing facility in Querétaro in 2005. To ensure sufficient numbers of skilled workers, Mexico’s federal and state governments established the Universidad Nacional Aeronáutica de Querétaro, which works in partnership with the École des métiers de l’aérospatiale de Montreal. Bombardier itself provides curriculum advice and equipment to the educational institutions.

In just under a decade, Bombardier Aerospace has doubled its capacity and investment in Mexico to meet demand for carbon composite structures, electrical harnesses, wing assembly, and sub-assembly systems installation. Through its operations in Mexico, Bombardier has reduced its reliance on third-party suppliers. The use of inputs from all three NAFTA countries increases the profitability of Bombardier aircraft. Bombardier Aerospace employs more than 1800 workers in Mexico; their efforts have allowed the company to maintain and expand Canadian employment in design, engineering, management and marketing.

Linamar

Headquartered in Guelph, Ontario, Linamar designs and manufactures precision engine and transmission components and assemblies. An international automotive leader, the company also produces for the consumer, industrial and energy sectors.

Linamar began manufacturing in Mexico in 1998, first to supply General Motors with transmission components. Subsequently it acquired a plant to build diesel engines for Renault. In 2002, Linamar acquired Federal-Mogul’s camshaft manufacturing operation in Saltillo, Mexico. Today, Industrias Linamar de S.A. is based in Durango, Mexico, and employs approximately 1,100 workers.

Linamar’s management philosophy seeks to balance global competitiveness with customer and employee satisfaction. The focus on maintaining a strong Canadian workforce both in terms of number of jobs and worker satisfaction has helped to facilitate Linamar’s global expansion efforts. About half of the company’s 16,000- person workforce is located in Ontario, serving as a hub for manufacturing activities in Mexico, France, Germany, Hungary and China.

Over the past two decades, Linamar has married Canadian expertise in higher-valueadded technologies with a Mexican workforce that is hardworking and increasingly skilled. Canadian personnel have provided essential training and capacity-building in the company’s Mexican plants.

Automotive components are often large and cumbersome to transport, so assemblers prefer that upstream suppliers locate nearby. Collaboration on technology and training between Canada and Mexico means that both sides are working with familiar processes and organizational cultures. This provides a distinct advantage over outsourcing between unrelated firms.

Linamar’s success demonstrates how specialized, higher-wage Canadian firms can prosper despite the movement of vehicle assembly operations to lower-cost sites. NAFTA plays an important role by ensuring tariff-free access and closely aligned rules and regulations. But the NAFTA advantage is eroding.

Upstream suppliers in the auto sector can thrive only when they can tap into a critical mass of final assembly activity. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are looking farther afield to emerging markets in Asia and elsewhere for market and cost advantages. This underscores the need to focus on strengthening the North American commercial framework, which in turn requires renewed efforts to reduce duplicative or inconsistent regulations and border barriers.

Palliser Furniture

Palliser Furniture Upholstery Ltd. was established in 1944 in the Winnipeg basement of Abram Albert DeFehr, an immigrant from Russia. Today, with manufacturing facilities in Canada and Mexico, Palliser is one of North America’s leading furniture manufacturers, specializing in made-to-order leather products.

Efficiency and proximity to customers were key reasons behind Palliser’s expansion to Mexico in 1998. At the time, the company was finding it prohibitively expensive to transport upholstered furniture from Manitoba to retailers in the U.S. South.

Currency risk was a second motivator for Palliser’s expansion, especially when the Canadian dollar began to climb relative to the U.S. dollar in the late 1980s. Even though the dollar dropped again in the 1990s, continued volatility suggested the need to diversify manufacturing sites to mitigate risk.

While Palliser chose a Mexican strategy, many North American manufacturers went to China. During the early- and mid-2000s, nearly all higher-volume, lower-priced furniture manufacturing moved to China, where costs were about 50 per cent lower. However, Palliser found a niche with customized products that use high-end materials and specialized designs. This type of production required a level of manufacturing quality and supply-chain flexibility that the company felt could not be achieved in China.

Today, most of Palliser’s manufacturing for the Canadian market takes place in Winnipeg, while the Mexican plants service the U.S., Mexico and Latin America. It takes about five weeks from receipt of the initial order to deliver a final, custommade product to the customer’s door.

Social and ethical considerations factored into Palliser’s location decision. The family’s experiences with Soviet Communism made them averse to locating in China. In Mexico, they avoided regions with a reputation for labour and social instability.

After visiting nine states and 20 cities, Palliser CEO Art DeFehr selected the state of Coahuila as the location for Palliser’s three plants because of its good security and strong industrial core.

Palliser currently employs 1,131 people in Mexico. The facility in Matamoros, Coahuila, handles all of the cutting and sewing of leather and fabric covers. There are two assembly plants in Saltillo, Coahuila, and this is also the site of corporate offices that manage operations for the Mexico and Latin American markets.

While expansion has not been without challenges, the decision to diversify its production to Mexico has helped Palliser adapt to the changes in Canadian currency and the powerful impact of China on manufacturing. In the process, the Canadian and Mexican operations have developed important and sometimes unexpected synergies. These include:

Technical and innovative capacity – Low-cost labour was the initial driver for the move to Mexico. However, Palliser soon found engineering talent within its Mexican workforce. Today, many of Palliser’s improvement initiatives begin in Mexico and are shared with their Canadian counterparts. Most recently, Palliser has begun to develop specialized testing for electronic components spearheaded by a young Mexican mechatronics engineer.

Procurement – Palliser has a network of Mexican suppliers that can offer competitive pricing without long lead times. Local sourcing of key components such as leather and foam has strengthened Palliser’s ability to respond to custom orders.

Redundancy – Machinery breakdowns are an operational reality but Mexico and Canada can readily produce components for each other in times of emergency. The speed at which Palliser can react has been greatly improved as a result of having equipment in both locations combined with frequent truckloads between countries.

Future opportunities

The Conference Board of Canada has identified a number of sectors in which Mexican demand growth intersects with Canadian trade capacity. These include:

- paper products

- steel products

- motor vehicles and parts

- transportation equipment (rail and aerospace)

- mobile telecommunications

- mining (gold and silver)

- construction services

- financial and insurance services

- energy services (oil and gas)

- electricity utilities

In addition to these sectors, Canada has a growing presence in:

Banking and financial services – Canada’s reputation for strong and stable financial institutions earns high marks in Mexico. Growth of private sector lending for consumers, business and infrastructure development should yield expanded future opportunities, due in part to recent reforms (see below).

Aerospace – Bombardier’s experience exemplifies the advantages for Canadian aerospace companies. The establishment of a strong aerospace cluster provides easy access to skilled workers and organizational expertise.

Automotive – NAFTA’s integration of the North American automotive market created opportunities not only for original equipment manufacturers but for Tier One and Tier Two suppliers. Canadian auto parts companies such as Linamar and Magna have successfully made use of Mexican manufacturing capacity and Canadian design and marketing.

Mining – Since Mexico relaxed its constraints on foreign investment in 1992, Canada has become the largest foreign investor in Mexico’s mining sector. Mexico is the world’s largest producer of silver and ranks among the top 10 producers of gold, fluorite, bismuth, celestite, sulphate and many other minerals. Proposed tax reforms may affect future profitability for foreign mining operations in Mexico, but the government has shown flexibility in other sectors to reduce the impact of reforms on foreign investors. Canadians are a welcome addition to the mining sector, not just because of the money they invest but also thanks to their use of cleaner, more efficient technologies and their principled approach to corporate social responsibility.

Energy – Although companies such as TransCanada are present, Canadians have not been highly invested in Mexico’s energy sector because of the state monopoly on oil production (see below). EDC estimates that Mexico’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), currently has about 100 Canadian suppliers. If proposed reforms are successful, there may be considerable opportunities for upstream and downstream services. Canada has an excellent reputation and Mexico is looking to Alberta and the National Energy Board for best practices in contract administration. Mexico produces natural gas and shale gas, but it is expensive and distribution infrastructure is poor.

Agri-food – Mexico’s growing middle class is consuming increased quantities of prepared foods and protein. There is a particular niche in specialty health, low-fat, or organic products. Unprocessed agricultural products such as pork, wheat and canola are sought by Mexican food manufacturers such as the bakery giant Grupo Bimbo, which owns a number of U.S. brands. And Canada’s seeds and genetic products provide Mexico with high-quality inputs that will eventually find their way to store shelves in Mexico and around the world.

Education – Mexico’s upper class is a large consumer of overseas education as a means of acquiring language skills and international experience. Canada is seen as a safe and affordable alternative to the U.S., but the visa requirement has dampened the flow of students. Of the 24,000 Mexican students who go abroad each year, about 50 per cent go to the U.S., 20 to 30 per cent go to Spain and only five per cent to Canada.

Students from well-off families tend to use their undergraduate years to develop business and social networks, so they generally do not spend the full period at foreign universities and colleges. However, there are still numerous opportunities for Canadian service providers in the areas of secondary education, language summer camps, semesters abroad, and post-graduate training. Moreover, there is also a demand to link Canadian and Mexican colleges and training institutes to provide practical training for energy, aerospace, automotive and other specialized fields. Training partnerships can also facilitate mutual recognition of certification in skilled trades, making it easier to move job-ready workers to any site within the NAFTA zone.

Information and Communications Technology – Mexico’s youthful and increasingly educated population is a ready incubator for high-tech start-ups as well as more established companies looking for programming, data management or content development skills. The ability to collaborate over long distances and store data in the cloud means that Mexican knowledge workers can locate anywhere. There are, however, clusters developing in Tijuana and along the northern border to take advantage of venture capital and expertise from Silicon Valley and Southern California. This convergence of capital and knowledge resources in a reduced-risk environment should be particularly appealing to Canadian start-ups and SMEs. Moreover, since most Mexican technophiles are fluently bilingual, a base in Mexico can help Canadians serve the world’s 400 million Spanish speakers.

The expected reforms in the telecom sector (see below) should create opportunities for Canadian companies in the areas of mobile telephony and broadband, including mobile services bundling and advanced data devices, applications and infrastructure for services on the cloud, and applications for smartphones, mobile banking and electronic commerce.

Mexico’s reform agenda

The government of President Enrique Peña-Nieto, who took office in December 2012, has embarked on a far-reaching reform agenda covering energy, telecommunications, finance, fiscal policy, education and labour. If successful, the reforms will generate significant economic and social benefits, increasing opportunities for a broader cross-section of Mexicans and building the country’s stock of social capital. Mexico will become a more competitive, stable and prosperous trading partner. In addition, many of the sectoral reforms will provide new opportunities for Canadian entrepreneurs. While many of these reforms have passed initial Congressional hurdles, the bigger challenge of secondary legislation and reform implementation remains.

Energy

Mexico is a significant but not particularly efficient producer of crude oil, ranking as the world’s 10th largest producer and 12th largest exporter. About half of Mexico’s oil is exported, mostly to the U.S. Pemex is the only company authorized to conduct exploration and development in the oil and gas sector.

Mexico’s access to ‘easy oil’ has run its course. Over the past eight years, crude oil production has decreased by a million barrels per day despite record levels of investment. Pemex is unable to satisfy Mexican demand for gasoline and diesel fuel; it imports 49 per cent of domestic consumption as well as 65 per cent of its petrochemicals and 33 per cent of its natural gas. Inefficiencies in the energy sector diminish Mexico’s export returns and make energy-intensive manufacturing unprofitable.

The reforms approved in late 2013 by Mexico’s Congress grant foreign companies exploration and extraction rights, effectively ending Mexico’s national energy regime, as Pemex becomes one competitor among many. Foreign companies will also be permitted to operate in such areas as refining, petrochemicals, storage and transportation (pipelines and rail). In addition to overall improvements in efficiency, Mexico has signaled an interest in foreign participation in oil extraction in deep water, lutite rocks and mature fields as well as shale gas and oil development.

While Mexico has agreed to the constitutional changes necessary to carry out the reforms, passage of secondary laws to establish a new contracting regime – and the establishment of infrastructure to operationalize it – will not be easy. A more open and vibrant energy sector should provide opportunities to Canadian companies, particularly in services, but increased Mexican crude oil output will also compete with Canadian exports. It is expected that the more lucrative contracts will remain under Mexican control.

Telecommunications and Broadcasting

A few large providers dominate Mexico’s telecommunications and broadcasting sector and there has been little investment in infrastructure or technology to improve access and reduce prices for consumers. The new reforms will allow 100 per cent foreign ownership in the telecommunications sector and 49 per cent foreign ownership in the radio and television section, as long as Mexican firms enjoy reciprocal access.

The first priority for Mexico’s newly created telecommunications regulatory body is to ensure that América Móvil, the dominant telephone operator (controlled by the world’s richest man, Carlos Slim), shares with other operators the so-called “last mile” of its network that connects phone and internet services directly to customers.

Although the telecom reforms were passed by Congress in June 2013, the secondary legislation required to implement them is not expected until early- to mid-2014. Mexico’s large providers have slowed or suspended domestic investment until more details are known about the secondary legislation, so affordable and efficient telecommunications is still out of reach of Mexican consumers.

Fiscal reforms

Mexico’s fiscal reforms are intended to help alleviate poverty and income inequality by increasing tax revenues. At around 10 per cent of GDP, Mexico has one of the lowest tax revenue levels in Latin America, and the government depends on energy returns from Pemex for a third of its revenue.32 While the reforms run the gamut of new revenue schemes, including a junk food levy, new taxes on mining profits are of major concern to Canadian investors. If implemented, the new laws will impose a 7.5 per cent mining royalty on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. Other reforms that may affect Canadians are new value-added taxes in the maquiladora (contract manufacturing) sector and new taxes on stock market profits and dividends.

Banking and financial services reforms

Mexico’s financial services reforms, signed into law in January 2014, seek to increase competition and lower the cost of borrowing. This is especially important for Mexico’s small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), which generate 35 per cent of GDP and contribute seven out of 10 formal jobs but often lack access to credit except through loan sharks. Unlocking low-interest loans will help SMEs grow and prosper.

The reforms promise to expand SME credit through increased scope for lending by government development banks. Changes to banking legislation will also make it easier for commercial banks to collect on loan guarantees in the case of nonpayment.

Since foreign banks and financial services companies already operate relatively freely in Mexico (controlling some 80 per cent of Mexican banking assets), the reforms signal opportunities for Canadian firms to provide more commercial loans in Mexico with reduced risk and more transparent processes.

Leveraging the Canada-Mexico Partnership to Strengthen our Global Competitiveness

Canada, the U.S. and Mexico are among each other’s largest trading partners and enjoy the benefits of an integrated market through NAFTA. However, the agreement has not had a major update since its inception in 1994 – prior to the rise of electronic commerce, digital service delivery, advanced manufacturing, third-party logistics and many features of the globalized economy that we now take for granted.

Since there is no appetite in the U.S. to update NAFTA directly, indirect routes are the only option. Canada, the U.S. and Mexico are negotiating parties to the TPP and any benefits conferred by the TPP that go further than NAFTA will take precedence. The TPP, together with our respective agreements and/or negotiations with the European Union, should help to modernize NAFTA commitments and expand Canadian access to new markets.

The problem with reforming NAFTA through the TPP is that the negotiating priorities of countries such as Vietnam and New Zealand will seldom match North American priorities. In terms of market access and reduction of non-tariff barriers, NAFTA’s commitments are already much deeper that what will likely be achieved in the TPP. Meanwhile negotiations with the European Union in areas such as regulatory alignment, food safety, certification, and dispute settlement have been (for Canada) and will be (for the U.S.) focused on reconciling fundamental differences between EU and NAFTA systems.

With TPP and EU negotiations providing improvements at the margins and no prospects for direct, comprehensive NAFTA reform, new Canada-Mexico initiatives, particularly those with strong business buy-in, will be key in strengthening the relationship in coming years.

In places where the TPP can build upon NAFTA, a coordinated effort is required. For example, three different sets of rules of origin for automobiles will confound the intentions of an integrated auto market. New TPP rules of origin must allow for cross-cumulation of NAFTA content. Similarly the battles fought by manufacturers and regulators to align standards and reduce technical barriers within North America will be for naught if manufacturers must adopt different standards to trade with the European Union.

Leveraging the benefits of Mexico’s trade agreements is a useful way to improve Canada’s access to other Latin American markets. Canada currently has agreements with Panama, Honduras, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru, and Chile. Mexico has recent agreements with all of these countries as well as with Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala and Uruguay. By seeking to match at least some of Mexico’s agreements, Canada can achieve relatively straightforward access to new markets given that 20 years of NAFTA disciplines have fundamentally aligned our domestic trade regimes.

The Pacific Alliance is another tool to deepen and widen the regional trade prospects. Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Peru launched it in 2012 to address trade and commercial issues such as the movement of workers, tourism trade, electronic commerce and digital services. Costa Rica has joined the Alliance and observer states include Canada, Guatemala, Panama, Uruguay, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Spain. Although such an ambitious agreement may be difficult to conclude, the forum for negotiation among forward-leaning trading nations will help to set the agenda for other negotiations such as the TPP.

Next steps in the relationship

Robust relations with Mexico within a strong NAFTA community provide Canada with access to a young, growing and increasingly prosperous Mexican market. It allows us to build on existing linkages with U.S. supply chain partners to engage with Mexico in a lower-risk, higher-return environment, and it helps to generate greater economic prosperity collectively than we could achieve on our own.

In short, Canada’s competitiveness in the world requires that we get it right in North America.

One of the first strategies for strengthened relations is to ride the shoulders of giants. Large Canadian companies have cleared a path for smaller market entrants and serve as a hub for integrated supply chains. Reducing barriers and building relationships requires a whole-of-business approach. One idea might be to start with a sector such as aerospace or auto-parts and then identify – and work to mitigate – all of the associated regulatory, border, and human capital barriers within the North American context.

A second important lesson is that strong relationships are key to business success in Mexico. Canadian business people in Mexico complain that our social and cultural relationships are shallow because diplomatic efforts are weak and inconsistent. We plant the seeds of the relationship through educational exchanges, innovation programs, technical assistance and trade promotion programs, but we do not tend to them long enough to develop strong roots. (Quebec may be the exception as the province tends to invest in longer term cultural and social ties with Mexico.)

Mexican alumni who have attended Canadian institutions are not encouraged to promote stronger business relations. Visa barriers have also quelled the desire to visit or study in Canada. Mexican business groups in Canada lack vigour because of negligible Mexican investment in Canada. Lack of current Mexican investment also signals to potential investors that Canada is not a very interesting market. Without robust, multi-level business, cultural and academic exchanges between the two countries – and among sectors, regions, and cities – we will continue to lack the means to nurture future business growth.

Priorities for policy action include:

- Removing or fundamentally reforming the visa requirement for Mexican nationals. As a first step, the government should consider an online screening program similar to the U.S. Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) for travellers from visa-waiver countries such as the United Kingdom. Once travellers have submitted basic personnel, passport and security information online, authorization is provided almost immediately. Until Canada is able to implement an ESTA-like system of its own, it should allow Mexicans who hold a valid

U.S. visa to enter Canada. - Finding ways to trilateralize progress in bilateral regulatory cooperation and border facilitation programs. At minimum, this

should involve appointing a Canadian observer to the Mexico-U.S. regulatory and border programs. Similarly, a Mexican observer should be assigned to the Canada-U.S. programs. As the Beyond the Border and Regulatory Cooperation initiatives conclude their first phase of activities, the process could be invigorated by launching pilots to identify and reduce major impediments in automotive and aerospace – sectors in which strong trilateral complementarities already exist. - Establishing new mechanisms for cooperation on energy and the extractive sector. As Mexico’s reforms in these sectors take effect, efforts by Canadian federal and provincial governments to provide advice on reform implementation could provide Canadian companies with an inside track on potential opportunities, within a set of rules with which they are familiar.

- Continuing to focus on meaningful cooperation with Mexico and the U.S. in the TPP and other trade negotiations of mutual interest. Sitting at the same negotiating table is not the same thing as working together. Areas of common interest in the TPP include market access and reduction of non-tariff barriers for North American automotive and meat exporters, and cross-cumulation of rules of origin.

- Significantly expanding educational opportunities – including grants and scholarships – for Mexican students in Canada and linking educational service promotion with the development of joint vocational and certification programs in the skilled trades.

- Investing in the bilateral relationship through state visits, parliamentary exchanges and trade missions. To be successful, Canada’s re-engagement with Mexico requires sustained and visible efforts.