Canada’s International Education Strategy

Time for a fresh curriculum

Introduction – A Tale of Two Countries

A quick glance at the official websites promoting Canada and Australia to foreign students is all it takes to know which country is doing the better job of drumming up interest around the world in its universities and colleges.

The Australians pull the reader in. “Why Australia?” reads the headline on one side ofthe home page at www.studyinaustralia.gov.au. On the other, a panel tells the story of Uttam Kumar, a 22 year-old Indian who recently won a government-sponsored contest for a year’s free study in Australia, return flights, accommodation, a stipend, and a possible internship.

Canada, by contrast, has two official websites promoting international education — one designed by the federal government, the other by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), the body representing provincial and territorial education ministers.

Both Canadian sites have a dull, bureaucratic feel, starting with their URLs:

www.cic.gc.ca/english/Study/index.asp

and

http://www.educationau-incanada.ca/educationau-incanada/index.aspx.

“Study in Canada,” intones the federal site’s headline. “Apply to study in Canada, extend your study permit, work while you study or get teaching material.” There are no personal stories, no eye-catching contests, and no content to persuade students to apply to Canadian programs.

Behind the contrasting websites lies a deeper and more sobering story. Canada has fallen behind Australia and other advanced economies in seizing the opportunities presented by the burgeoning business of cross-border education. These opportunities go well beyond the number of students a country attracts or the money they spend. International education is fast becoming a valuable tool in trade, development aid, and diplomacy. In other words, it plays an increasingly visible role in the way that a country projects itself on the world stage. Furthermore, education agreements are likely to fulfill much the same role as trade agreements in deepening bilateral relationships and liberalizing the movement of people across borders.

And the importance of this soft power is growing. The UNESCO Institute of Statistics estimates that about 3.8 million students were enrolled in tertiary education outside their home countries in 2011, almost double the number in 2000. Their ranks are expected to swell to seven million by 2020, with at least half seeking their education in English.

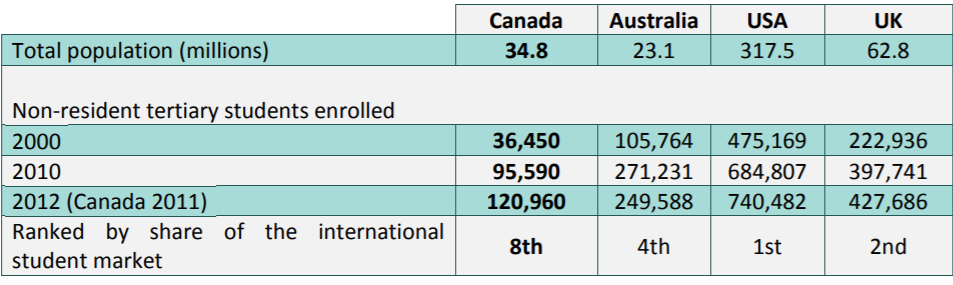

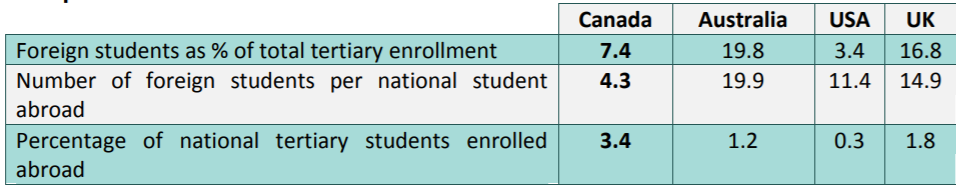

Yet, as the tables below demonstrate, Canada is punching well below its weight compared to its rivals:

International student enrollments

In-depth

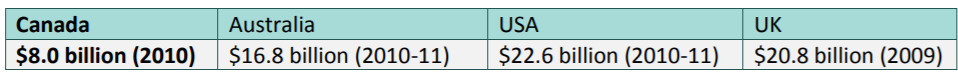

Estimated economic benefit* from incoming international students

Source: International Education: A Key Driver of Canada’s Future Prosperity, August 2012

Canada’s record is especially dismal in attracting international students from China, by far the largest source of international students globally. According to UNESCO, Chinese students comprised almost 20 percent of all tertiary-level international students globally in 2012. Almost a third of them were studying in the United States, 14 percent in Japan, 13 percent in Australia, 11 percent in the UK, and just 3.8 percent in Canada.

Canada has only started to rise to the challenge. The federal government and many provinces, notably British Columbia, have taken significant steps to sharpen our country’s competitive edge over the past three years.

Even so, a combination of turf battles, excessive bureaucracy and, most of all, a dearth of leadership and imagination continue to hold us back.

Echoing many others in the field, Sonja Knutson, director of Memorial University’s International Centre, says: “We’re not used to marketing ourselves. We’re used to students coming to us because we’re Canadian and we’re nice.” Glen Jones, professor of higher education at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, adds: “Australia treats this as a major industry. Canada is starting to think that way, but is still some distance from it.”

Beyond Profit

As international education has mushroomed, perceptions of its value have undergone several transformations. The advantages of studying in another country took hold in the 1980s when developed countries — including Canada — began taking in significant numbers of foreign students as a component of their aid programs. Scholarships for promising

students in the developing world were seen in those early days as a quick and effective way to bring badly needed skills to impoverished parts of the world.

Growing demand for a high-quality education combined with rising incomes — especially in Asia — and a surge in mass air travel soon added a commercial dimension. Universities, colleges, and elite schools — mostly in the English-speaking world — began to see foreign students as useful sources of revenue. As a result, a vibrant new industry was born.

Globe-trotting students typically pay far higher tuition fees than locals, turning them into a valuable profit centre for cash-strapped institutions. Indeed, foreign students have become an indispensable part of funding many higher-education institutions in Europe, North America, and Australia. To take a random Canadian example: The international student fee for a six-credit arts course at the University of Manitoba is AD$2,187.60, or 3.5 times more than the CAD$624.90 that Canadian residents pay. International students make up 13 percent of that university’s enrollment.

Likewise, local communities have come to recognize foreign students as an economic force to be reckoned with. Besides tuition, they spend significant sums on accommodation, food, entertainment, local travel, and a host of other outlays. Education was Australia’s fourth largest export earner in 2011, pulling in AUD$15.7 billion. In the state of Victoria, it was the top export — ahead of personal travel and wool. Universities UK, a British lobby group, estimated in a March 2014 study on the impact of universities on the UK economy that each non-EU student contributed over £24,000 to Britain’s GDP and created 0.45 full-time jobs.

In Canada, Roslyn Kunin & Associates, a Vancouver-based consultancy, estimated in a 2012 report commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade that international students spent CAD$7.7 billion in 2010 — more than Canada’s export earnings from unwrought aluminum or aircraft — creating 81,000 jobs and generating CAD$445 million in tax revenues.

Profit remains the driving force behind Canada’s International Education Strategy. As Ed Fast, the international trade minister, put it in January 2014:

“Our government recognizes that international education is a key driver of jobs and prosperity in every region of Canada. . . . [T]his strategy will also help us advance Canada’s commercial interests in priority markets around the world and ensure that we maximize the people-to-people ties that help Canadian workers, businesses and world-class educational institutions achieve real success in the largest, most dynamic and fastest-growing economies in the world.”

However, with the surge in globe-trotting students since the turn of the century, the realization has dawned on policymakers that international education offers wider benefits. As Jennifer Humphries, vice-president at the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE), which represents a wide range of education institutions, puts it: “It’s about always seeing it as a two-way street, always seeing it as a mutually beneficial activity. Educators are wired for that. It should always be coupled with a sense that we shouldn’t be the only ones benefiting.”

Outbound students

The United States, the European Union, and Australia — but so far not Canada — have launched ambitious programs to encourage their own citizens to study abroad. The rationale is that these young ambassadors will build valuable contacts in the countries where they study and, in so doing, deepen educational, business, cultural and even political ties.

The Obama administration unveiled a “100,000 Strong” initiative in 2009 with the goal of dramatically increasing and diversifying the number of American students studying in China. The Chinese government funds 10,000 of the scholarships. A second 100,000 Strong program covering Latin America and the Caribbean was launched in 2011.

The State Department notes that “the purpose. . . is to foster region-wide prosperity through greater international exchange of students, who are our future leaders and innovators. . . . 100,000 Strong will deepen relationships across the hemisphere, enabling young people to understand and navigate the rich tapestry of shared values and culture and lead the process of greater commercial and social integration key to our region’s long term security and prosperity.”

The 100,000 Strong initiative is now administered by an independent, non-profit organization. A matching grant program aims to encourage private and corporate donations for scholarships.

Australia launched a similar “scholarship and mobility program”, known as the New Colombo Plan, in February 2014. The scheme is designed to help Australian undergraduate students study abroad and, where possible, sign up for overseas internships or mentorships related to their studies. They are also encouraged to learn a foreign language. Under a pilot phase, the government has provided funding to 24 universities, enabling about 300 students to study in Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and Japan. The plan also encourages universities to use alumni networks and corporate links to facilitate internships and mentorships for students. Rebecca Hall, director of international education in the state of Victoria’s Department of State Development, Business and Innovation, observes that, “the New Colombo Plan is giving some important signals to our partners in east Asia that we are serious about reciprocity.”

Partnerships and other forms of collaboration

The drive by China, India and other emerging economies to improve the quality of domestic education has opened up vast opportunities for western institutions to set up local campuses, collaborate in research projects, and provide consulting services, among other ventures. Such partnerships can pay significant long-term dividends in the form of student and faculty exchanges and — less tangibly but no less importantly — a general improvement in goodwill and understanding.

Many Canadian institutions have already moved in this direction. Mitacs Inc., a pioneering non-profit based in Vancouver, supports groups of Canadians with strong relationships in other countries who see opportunities for collaboration in research, training, and entrepreneurship. For example, Mitacs’ Globalink Partnership Award enables graduate students from 18 universities to take part in 16- to 24-week research projects with companies in Brazil, China, India, Mexico, France, Turkey and Vietnam. International students studying in Canada are also eligible for the awards. The CBIE took 25 educators to Algeria in February 2014 at the invitation of that country’s Ministry of Higher Education for a conference aimed at developing bilateral partnerships between universities and technology colleges.

A growing number of universities and colleges are seeking to expand international student enrollment at offshore locations. “For us, it has become a natural thing to be acting locally and globally both at the same time”, says Keith Brown, vice-president for international and aboriginal affairs at Cape Breton University, which offers its degrees in Egypt and Kuwait and is planning a “co-operative offshore delivery” program in China. Spelling out the benefits, Dr. Brown says: “First, we’re in the region, and that’s quite public and high-profile within some areas. Canadian ambassadors preside at convocation. The inter-cultural learning and the need to globalize curriculums. . . in part it comes in discussions with your partners, and then you realize how this benefits your students on campus in Sydney. It is 2014. Things are so globalized in post-secondary education.”

Education as a diplomacy

Education is increasingly recognized as a valuable foreign-policy tool. “It is not just about education,” Australia’s education minister, Christopher Pyne, said in October 2013 in discussing the new Liberal government’s international education policies. “It is about Australia’s soft diplomatic capacity, our place in a region where relationships are so important.”

Outlining the numerous “soft” benefits of international education, the United States’ 100,000 Strong website notes that the program “will deepen relationships across the (western) hemisphere, enabling young people to understand and navigate the rich tapestry of shared values and culture and lead the process of greater commercial and social integration key to our region’s long term security and prosperity.”

Education links can do much to boost a country’s profile abroad, an especially important consideration for second-tier markets such as Canada. To take one example: the University of Toronto reported in April 2014 that 740,000 users around the world had registered for one of its 13 MOOCs (massive open online courses). That is nine times higher than the combined enrollment at U of T’s three campuses. Two Australian researchers, Caitlin Byrne and Rebecca Hall (also quoted above), noted in a 2011 paper:

“Positive experiences of exchange and the development of intellectual, commercial and social relationships can build upon a nation’s reputation, and enhance the ability of that nation to participate in and influence regional or global outcomes. This is ultimately the essence of soft power.”

Risks

In the quest to reap the benefits of international education, we should not lose sight of some very real and potentially costly risks.

Experience has already shown that a steady advance in foreign student numbers cannot be taken for granted. The flow is vulnerable to a number of factors, including unpredictable shifts in public opinion on such emotive issues as immigration and preferential treatment of foreigners in the workplace. Canada has yet to experience such a backlash, but the recent furor over temporary foreign workers and simmering resentment in some quarters against immigrants could sour the mood towards foreign students.

Both the UK and Australia, the second and third biggest destinations, have seen marked reversals in recent years. And there are signs that outflows of students from some countries, including China, may be slowing. Even if overall numbers continue to rise as forecast by UNESCO and others, intensifying competition suggests that not all countries will benefit

equally.

Australia, long regarded as the standardbearer for international education, was buffeted by a series of setbacks in 2009 and 2010. First, a strong appreciation in the Australian dollar significantly raised the cost of study and accommodation for foreign students. Second, several privatesector colleges collapsed, leaving thousands of foreign students stranded and prompting the then-Labour government to tighten entry requirements, including a substantial rise in visa fees.

Third, a series of attacks on Indian students in Melbourne undermined Australia’s reputation as a safe home-away-from-home. A social-media frenzy in India fanned disquiet to the point where the Indian government accused Australia of not doing enough to protect its students.

The number of foreign students in Australia slumped by one-fifth between 2009 and 2012 while revenues from international education dropped from AUD$18.6 billion to slightly over AUD$14 billion. (Following a series of reforms, numbers are expected to start rising again in 2014.)

The UK, also accustomed to double-digit growth in international enrollments, saw its first decline since the early 1980s during the 2012-13 academic year. The inflow of students from Pakistan and India, in particular, has halved since 2010. A Higher Education Funding Council report, published in April 2014, ascribed the drop mainly to an increase in the cap on tuition fees at most British universities. Other experts have linked the reversal to moves by the current Conservative government to limit immigration and clamp down on unscrupulous private education providers. Janet Ilieva, the report’s author, told The New York Times that the drop could be a worrisome sign for future teaching and research capacity. “The implication is that this is putting the long-term viability of certain subjects under threat,” she said.

It would also be unwise to ignore the intensifying competition for foreign students. The United States is regaining its former reputation as a welcoming destination after the animosity that followed the 9/11 attacks.

Australia has eased visa rules so that even students from so-called “high-risk” countries such as China, India and Pakistan now need to show they have sufficient funds for only 12 months of study, down from the previous standard of 18 months. Australia has also relaxed its rules for English-language proficiency.

Elsewhere, institutions in France and Germany, among others, have started offering programs in English, putting them in direct competition with the United States, the UK, Australia and Canada. Among the latest to enter the fray is Denmark, which announced plans in early 2014 to step up funding for non-EU students and streamline visa and immigration rules. The Danish government emphasized the support it had received for these initiatives not only from higher education and research institutions, but also from the Danish business community.

The problem is that this global recruitment drive is heating up even as students in emerging economies, especially in Asia, are showing less interest in leaving home to further their education. The quality of education in countries such as China, India, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan has improved markedly, and that trend is sure to continue. The exodus of students from China already shows signs of slowing. According to UNESCO, the number of Chinese students studying abroad soared from 141,000 in 2000 to 650,000 in 2011. But the outflow slowed to 646,300 in 2012.

The bottom line is that ambitious targets for foreign student enrollments could become more difficult to achieve in the years ahead. With that in mind, many experts are urging governments and educational institutions to shift the emphasis from quantity to quality. Graduate students, for instance, are often able to afford higher fees, require less intensive instruction, and are more likely than younger, more footloose undergraduates to stay on after their studies and contribute to the domestic economy. “The increased risk doesn’t mean we should turn away from this,” says Professor Andrew MacIntyre, deputy vice-chancellor for international education at RMIT University in Melbourne. “It just means we need to invest even more thought, effort and energy into doing it as well as we can.”

In Canada, Memorial University is among those attempting to make this shift. It is putting less emphasis on the overall number of foreign students, seeking instead to match enrollment more closely to the needs of the province’s economy and changing demographics. For example, it has identified engineering as a priority, and is tailoring recruitment campaigns accordingly.

The Canada Advantage

Canada seldom appears right at the top of rankings typically used to measure competitiveness in international education. The overall standard of Canadian education is high, but not the highest. University and college fees are competitive, but not the most competitive. Moreover, Canadian institutions are active in research, but not as active as many others, especially in the United States.

Even so, Canada offers an overall package that few, if any, other countries can match. Foreign students are also drawn by our reputation as a tolerant, multicultural society; by our proximity to the United States, without being part of the United States; and, not least, by a widespread perception that Canada is one of the safest places on earth. Being an English-speaking country is another big plus. The OECD estimates in its Education at a Glance 2013 report that the United States, the UK, Canada, Australia, and Ireland combined to account for 40 percent of the increase in enrollments of foreign students in tertiary education around the world between 2000 and 2011.

Canada’s student immigration policies are the envy of its rivals, including Australia. Under current rules, foreign students can work part-time while they study, and for up to three years after graduation. Further refinements took effect on June 1, 2014 (see page 16). Many universities and provincial agencies help foreign students find work both during their studies and after graduation. Manitoba, one of the most determined provinces in courting foreign students, has opened the door to immigration by allowing foreign graduates of post-secondary institutions in the province to apply for inclusion in the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program (MPNP) after working in the province for just six months.

Canadian educational institutions also have substantial capacity to accommodate more foreign students. In Australia, foreigners make up almost 45 percent of the student body at the University of Ballarat near

Melbourne, and the proportion is above 25 percent at about a dozen other universities. By contrast, the highest proportion in Canada is about 30 percent, and far lower at the overwhelming majority of institutions.

The proportion of foreign students at the University of British Columbia is a relatively modest 17 percent, and 15 percent at the University of Toronto.

Canada’s Challenges

1.Whatever Canada’s advantages, we must also contend with some significant drawbacks:Absence of a unified and coherent voice promoting Canada abroad. Canada is the world’s only developed country without a national education ministry or a national education strategy. CMEC published an international education marketing plan in 2011 that summed up the problem:

“Efforts to promote Canada’s education systems abroad involve multiple actors, not only provincial/territorial departments of education and educational institutions, but Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program According to the program’s website, more than 15,000 newcomers move to Manitoba each year under the MPNP. If a Manitoba employer extends an offer of employment of six months or more in duration to an international student who has graduated from a post-secondary institution, that graduate is on track to becoming a permanent resident of Canada. In this way, the government of Manitoba is ensuring future job growth and a constant stream of new, skilled recruits in key industries. Canada’s International Education Strategy – Bernard Simon also the immigration departments of both levels of government, as well as the federal departments responsible for foreign affairs, international trade, and international development. At the same time, provinces and territories are competitors for students in the international market, a reality that places some limits on the potential for collective action. Thus, the challenge in Canada is one of multilaterally coordinated government action to promote its education systems abroad.“

“Stakeholders have consistently complained that the lack of coordinated action harms marketing efforts and, in the absence of a clear collective vision of how to proceed, they have called upon the federal government to exercise greater leadership in this area.”

This fragmented marketing effort helps explain why Canada has lagged Australia and others in making inroads in the key Chinese market. No matter how vigorously the provinces seek to drive home the message that they have full authority over education, Chinese officials have balked at doing business with them individually. The Chinese attitude is simple: If Australia and every other country can speak with one voice, why can’t Canada? But instead of capitalizing on the strong Canada brand, the provinces have sought to mollify the Chinese by channeling collaboration through CMEC, the body representing the 13 education ministers. CMEC held its third “High-Level Consultation on Education Collaboration between the Provinces and Territories of Canada and the People’s Republic of China” in Edmonton in February 2014.

2.Inadequate official data on international education hampers informed decisions. Professor Lesleyanne Hawthorne, a global migration expert at the University of Melbourne, cites numerous examples of data critical for market research that is available in Australia but not Canada. Among them: sectors of enrollment; wages and other employment details of former students who have remained in the country either as landed immigrants or temporary residents; and monthly enrollment statistics by sector, discipline, level of enrollment, source country and type of institution. Professor Hawthorne has published a study of international medical students who qualified in Australia (many of them Canadians). The study, based on a national survey administered by medical school deans, assessed the students’ experience in the first and final years of their studies, and the first year after they qualified. The raw material for such research would not be available in Canada.

The paucity of statistics is partly due to fragmented jurisdiction over education. Moreover, neither the federal government nor the provinces have given sufficient attention to this unglamorous yet essential tool of sound decision-making. A fivemember panel on labour market statistics, led by former Toronto-Dominion Bank chief economist Don Drummond, reported in 2009: “We were struck by the fact that even relatively straightforward educational data on colleges and degree-granting institutions. . . are unavailable or years out of date. . . . This result is starkly at odds with the aspirations of a knowledge-based economy and society.”

3.Canadian institutions and policymakers all too often view international education through the narrow lens of boosting student numbers and revenues. This is especially true in regions where universities and colleges have turned to foreign students to counter a decline in local enrollment. It is no accident that the two universities that have the highest proportion of international students in Canada are St. Mary’s University and Cape Breton University, both in Nova Scotia. In each case, foreign students make up about 30 percent of total enrollment. As discussed above, international education is taking on a much broader dimension. If Canada fails to capitalize on this trend, it risks falling further behind, including in the continued flow of inbound students.

Recent Developments in Canada

The federal government and the provinces have started to recognize the shifting landscape of international education with a series of initiatives designed to reinforce Canada’s advantages and correct its shortcomings.

CMEC’s Marketing Action Plan

The Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) published an international education marketing plan in June 2011. The report, Bringing Education in Canada to the World, Bringing the World to Canada, recommended numerous measures to step up recruitment of international students, improve Canada’s share of the international student market, encourage foreign students to stay in Canada after they graduate, and create more opportunities for Canadians to study abroad.

CMEC’s flagship proposal was a branding campaign under the banner: Imagine Education au/in Canada. This slogan was designed to drive home the message that the Canadian educational experience has unrivalled value. As CMEC saw it, the brand conveyed openness and supportiveness through the concept of what it called “Empowered Idealism”.

The Imagine Education campaign has gained little traction. A review conducted by Ipsos Reid for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in early 2012 concluded that the brand “has some weaknesses which need to be addressed. Mainly, it is confusing and not seen as sufficiently linked to education and Canada. The absence of a clear national brand, which is present among Canada’s competitors, leaves participants wondering who the sponsor of the communications is.” Many of those interviewed for this paper expressed even more forceful reservations.

Despite the criticism, this initial branding exercise recognizes a crucial point: Canada’s brand carries more weight around the world than that of any single province or institution. “Publicly, it’s always Canada first and B.C. second,” says Randall Martin, president of the British Columbia Council of International Education (BCCIE), a provincial Crown corporation. Several provinces have quietly forged direct relationships with the federal government on international education matters in an apparent recognition that the path to future success lies in building on the Canada brand in a less timid way than has been the case up to now.

The federal advisory panel

A panel on Canada’s International Education Strategy, chaired by Dr. Amit Chakma, Western University’s president, submitted a 120-page report in August 2012 titled International Education: A Key Driver of Canada’s Future Prosperity.

The report recommended that Canada aim to roughly double its intake of full-time international students from 239,000 in 2011 to 450,000 in 2022, equal to a seven percent annual growth rate. This goal is considerably more aggressive than Australia’s target of raising enrollments by 30 percent by 2020. The rationale was that it would maintain Canada’s share of the projected international student market.

The panel took the view that the goal was realistic “given our assessment of the growth trends in international education, and Canada’s ability to sustain quality”. It added that “Canada’s education system has the capacity to absorb new international students without displacing domestic students.” The target would be met partly by expanding foreign student enrollment in elementary and secondary schools, and in language schools. Even so, it is open to question whether the report took adequate account of the risks of setting ambitious numerical targets, as outlined above.

The report also noted that, “given the inter-connectedness of the knowledge economy, Canada’s International Education Strategy must be a part of the government’s agenda to ensure policy alignment with economic, trade and immigration policies. Further, to engage in knowledge diplomacy, the . . . strategy needs to be integrated into official missions abroad.” The panel specifically identified the Prime Minister of Canada as a “unifying champion” for international education.

Federal International Education Strategy

The federal government responded in January 2014 with a new International Education Strategy that, in its words, “sets targets to attract more international researchers and students to Canada, deepen the research links between Canadian and foreign educational institutions, and establish a pan-Canadian partnership with provinces and territories and all key education stakeholders, including the private sector.”

Highlights of the strategy include plans to:

- Double the number of international students in Canada by 2022 (as proposed by the advisory panel).

- “Monitor and evaluate progress” toward this target in 2018.

- Increase the number of students who choose to remain in Canada as permanent residents after graduation.

- Develop an enhanced marketing and branding plan, including a new refreshed “brand” for the use of governments and key stakeholders.

- Give priority to six markets: Brazil, China, India, Mexico, North Africa and the Middle East, and Vietnam.

- Promote more partnerships between Canadian institutions and their foreign counterparts.

- Strengthen coordination among governments, with CMEC and other stakeholders.

- Regularly review the strategy and “adapt to meet developments and opportunities.”

- Budget CAD$5 million annually to implement the strategy, as provided in the 2013 federal budget.

New immigrant rules

The federal Department of Citizenship and Immigration announced significant changes in February 2014 in the regulations

governing foreign students in Canada. The new rules, which took effect on June 1, generally make it easier for international students to work in Canada during and after their studies, but also aim to curb abuses. For example, applicants for a study permit were previously allowed to enroll at any educational institution in Canada. Under the new rules, permits will be issued only to applicants planning to study at an institution designated by provinces to enroll international students. These institutions will need to meet minimum standards.

The Way Forward

Whatever their shortcomings, the above initiatives are a welcome step forward. They underline the importance of the international education sector and highlight the need for improved coordination among the various players. They also confirm that Canada can do much more to realize its potential.

However, any prescription for future action needs to take into account one immutable reality: whether we like it or not, some of the most daunting obstacles to progress are also the least amenable to change. No amount of carping or hand-wringing can alter the constitutional reality that education policy in Canada is fragmented and will remain so.

The recommendations below are guided by advice in a recent article by Lorna Smith, director of international education at Mount Royal University in Calgary: “I would like to recommend that we not view the future of Canada’s new International Education Strategy as ‘a glass half full or half empty’ to be debated. Rather let us just acknowledge that ‘the ball is now in our court’ and seize the opportunity!”

Recommendations:

A central theme of this paper is that enlightened international education policy is shifting from a focus on revenues generated by inbound foreign students, to a broader and more sophisticated approach.

In line with this trend, Canada needs to combine recruitment of foreign students with broader goals, such as encouraging domestic students to study abroad, partnerships and research collaboration with foreign institutions, and using education as a tool of “soft diplomacy”.

In short, education needs to be incorporated into Canada’s overall foreign policy. This includes wider use of international education — both in- and outbound — as a tool in development aid and a potential bargaining chip in future international trade agreements.

As part of this shift, less emphasis should be placed on specific — and potentially risky — numerical targets. Instead, the focus should be on attracting high-quality students whose skills match Canada’s needs.

It is indisputable that the Canada brand carries greater weight around the world than that of any single province or institution. All players need to consider the implications of this reality. By giving prominence to Canada, future brand and marketing campaigns should aim to project a unified message that can achieve the goals of each province and institution to an extent not possible by going it alone.

This does not mean abandoning the promotion of specific provinces or institutions. It does mean that Canada needs to be front and centre in future branding strategy and promotion campaigns.

Mapping a more effective international education strategy must thus start with a mechanism to improve coordination among the federal government, the provinces and territories, and the numerous other players in the sector. Without more effective coordination, Canada cannot reap the full benefits of international education. Every player in every part of the country, without exception, has a clear economic interest in pursuing this goal.

One way of achieving it is to set up a new Crown corporation, to be known as Education Canada, with a mandate to promote the federal government’s

International Education Strategy.

The corporation would absorb the existing Canadian Consortium for International Education and the Edu-Canada unit within the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development. It would be funded by the federal government and the provinces, and would have sufficient autonomy to act more nimbly than the groups that currently coordinate international education marketing and strategy.

Regional tensions would be mitigated by a board of directors representing various sectors involved in international education (such as universities, colleges, and primary and secondary schools), augmented by respected individuals with backgrounds in business, academia, civil society or social justice (among other fields). Such a board would be more inclined to consider the national interest than the interests of any specific region, province or institution.

Canada’s branding strategy needs more than a “refresh” as envisaged by the federal government’s international education strategy. It needs a bold and imaginative approach tailored to a global audience, and unfettered by parochial political concerns.

Education Canada would give high priority to devising a replacement for the largely ineffective “Imagine Education au/in Canada” campaign. It should also design a single official international education website that would not only provide information for incoming students but also feature opportunities for Canadian students abroad and news of collaborative projects involving Canadian institutions in other countries. The website would have links to individual provincial websites, and vice versa.

The government has correctly identified international education as a priority sector. It is a growing contributor to the domestic economy, and an increasingly valuable element in Canada’s foreign policy. Given this importance and the intense competition from other countries, Canada needs adequate resources to make its presence felt abroad.

If Canada is to reap the benefits envisaged in the International Education

Strategy, a substantially bigger investment will be needed than the $5 million a year currently budgeted.

With federal finances now moving into surplus, international education has a strong claim to a substantially bigger allocation in future budgets. These allocations should be channeled to Education Canada, the new Crown corporation.

Part of any extra funding should be allocated to a Canadian version of the United States’ 100,000 Strong program and Australia’s New Colombo Plan, the goal of which would be to encourage Canadians to study and conduct research abroad. Education Canada, the new Crown corporation, should administer the program.

The International Education Strategy proposes that Canada focus its efforts on six countries and regions: Brazil, China, India, Mexico, North Africa and the Middle East, and Vietnam. The rationale behind this decision is understandable: Canada has limited resources, and they should not be spread too thinly. However, such a narrow focus runs the risk that Canada may lose valuable opportunities not only in education but, more generally, in raising its global profile and burnishing its image elsewhere. Among current examples are Myanmar, Ecuador and parts of central and eastern Europe. In any case, universities and colleges are unlikely in practice to limit themselves to the priority markets identified by the federal government as they seek international students and opportunities for partnerships.

As Jennifer Humphries at the Canadian Bureau for International Education puts it, “If we’re being reached out to, let’s respond. If we don’t respond, someone else will.”

Australia’s International Education Advisory Council noted in its February 2012 report: “While we are in the Asian Century and there is a concerted effort to build on Australia’s role in the region, many universities and colleges have indicated that they are also increasing their efforts to attract students from the emerging regions of the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. . . . It is vital . . . that Australia does not neglect the rest of the world.” Canada should take a similarly flexible approach, guided by prevailing circumstances as well as the input of educational institutions.

Statistics Canada and the provinces already collaborate on a limited basis in collecting education data. This partnership should be widened to include not only data on the number of students in Canada and where they are studying, but the economic benefits they bring, and their reasons for being in Canada.

Business has a valuable role to play in realizing the full potential of international education. Already, many businesses fund scholarships, employ interns and generally help promote international education. Navitas, an Australian education provider, has established a presence on two Canadian campuses — Simon Fraser and the University of Manitoba. The company helps foreign students bridge the gap between their home qualifications and the standards needed for admission to a Canadian university. Meanwhile, 54 businesses in and around Halifax have joined the Greater Halifax Partnership Connector Program, which helps foreign students and immigrants find jobs. Similar programs have sprung up in numerous other cities.

Business should not stop there. It is in a strong position to press for cross-border education initiatives to be part of trade and diplomatic negotiations. In short, the voice of business needs to be heard more loudly in the evolving public dialogue on the benefits of international education.