Canada, China and Rising Asia: A Strategic Proposal

Joint Statement CCBC and CCCE

China and the Asia Pacific region as a whole are critically important to the future prosperity of Canadians. For that reason we are pleased to have sponsored this study by Wendy Dobson, Co-Director of the Institute for International Business at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. The purpose of this study – which is presented in English,

French and Chinese – is to inspire new thinking and new ideas that can help shape a long-term Canadian strategy in Asia.

Dr. Dobson presents a compelling case for much deeper engagement in the region on the part of Canadian businesses, governments and other stakeholders. She lays out a comprehensive roadmap, supported by an analytical framework that includes high-level economic analysis as well as regional and country-specific findings. The views expressed in this study are those of the author.

Canadians have awakened to Asia’s economic transformation, but the process is accelerating and we need to move quickly. The numerous challenges that we face are outweighed by tremendous opportunities. All of us must work together to ensure that Canada achieves its potential as a Pacific nation.

Executive Summary

Canada has a reputation in Asia of showing up there but not being serious about establishing longterm relationships. This was not always the case. In the past, we built strong bilateral relationships with Japan and China and contributed to international aid programs in India, Malaysia, and Thailand. Canada was also a strong supporter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in the early years following its founding in 1967. Today, Canada has no major comprehensive trade deals or investment agreements in the region—instead, such initiatives have stalled in the face of demands of special interests or for concessions identical to those made to Americans. Our absence from political-security forums matters deeply to traditional trading partners such as Japan and South Korea. The picture is one of an ad hoc approach, one that lacks a strategy toward developing both ties with Asia and a Canada “brand.”

Already, China has replaced Japan as Canada’s largest Asian trading partner, and China and other Asians are very interested in Canada’s energy and natural resources. Over the next two decades, Asia will undergo massive urbanization, and rapidly expanding middle classes will be demanding wealth management and other financial services, education, cleaner technology, and environmental improvements, all of which Canadians do well. As such demands grow, the region’s global supply chains will become more complex, and services, investment, and sales by foreign affiliates will be at the heart of trading arrangements. Canada cannot afford to be left out.

Canadian businesses are diversifying trade beyond their traditional dependence on the US market, responding to market forces rather than to any strategic policy shift. As policy does shift, the diversification should be viewed through a Canada-US lens. Canada’s long-term interests are served by the United States developing its own broad Asia strategy and by Chinese-US cooperation, even as they become rivals. Asia also faces the unique challenge of reconciling the aspirations and ambitions of its three giant economies, China, India, and Japan. It is in no one’s interest to see Asia turn inward and become preoccupied with competition among these three giants.

Canadians are beginning to realize the significance of Asia’s rising economic and political influence and the need to re-engage with the region. Bold leadership is now required to shape Canada’s response in a spirit commensurate with the region’s growing importance. Canada needs a generational, multi-dimensional economic strategy to support and advance its interests. Two pillars of any Canadian Asia strategy should be a serious commitment to politicalsecurity issues in the region and engagement through state-to-state relationships, which provide the foundation for commercial, political, and other relationships. To that end, Canada should restore its government’s regional presence through high-level relationship building. We should develop a Canada brand based on ambitious targets for trade and investment. These targets and relationships should be pursued on an ongoing, non-partisan basis supported by a coordinated strategy among the federal and provincial levels of government, the private sector, and other key stakeholders. We should also be thinking of Canada as an Asian location—for education, nonconventional energy, and even as a headquarters in the Americas for Asian multinationals.

A particular strategy, or roadmap, with respect to our relationship with China should also be an integral part of an effective Asia strategy—as indeed, an effective Asia strategy and the linkages it would create would be helpful in our dealing with China. A China roadmap should address mutual interests: ours in trade liberalization, investor and intellectual property protections, sectoral priorities, and China’s in flows of people, food security, market access to energy and natural resources, and the development of services such as education.

Central to a Canadian Asia strategy should be the active pursuit of our interests through regional and bilateral trade and investment liberalization. In the long term, Canada should diversify its trade with China by increasing its exports of knowledge-based goods and services that China cannot produce at this time. At the regional level, joining the negotiations on a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) would be the most efficient way for Canada to deepen its integration with other Asian economies, but only so long as we were willing to put all issues on the table, including supply management and the protection of intellectual property. If not through TPP, then an aggressive strategy of bilateral or other regional economic framework agreements will be necessary.

Commercial priorities will also reflect Canada’s strengths and challenges. Canadian natural resource companies and firms such as Manulife, BMO, Bombardier, and SNC Lavalin already have developed successful businesses in Asia over many years; we now need to build on these successes and overcome the major challenges that confront small and mediumsized Canadian enterprises as they attempt to move beyond their small domestic market and participate in the region’s supply chains. Finally, Canadians should realize that, over the next two decades, Asian producers will move into more direct competition with us as they develop their capabilities. To stay ahead, Canada will have to address its lagging productivity and other selfinflicted weaknesses to ensure we produce what Asians want to buy.

Overview and Introduction

The rise of Asia, where half of humanity lives, is transforming the world’s economic and geopolitical landscape. Six of the ten largest cities are there and, within twenty years, so will be three of the four largest economies: China India, and Japan. Even before the recent global financial crisis, Asia accounted for more than a fifth of the world’s real gross domestic product (GDP), but that share has now increased to one-quarter— and is even higher when measured by purchasing power parity. Asia’s economic dynamism—particularly China’s role as a leading world trader—helped pull the rest of the world out of the 2008–09 recession.

The speed of Asia’s transformation is unprecedented, and has been made possible by a world with open markets in which Asian economies have thrived and by the high savings rates of Asian citizens. As well, Asian governments have encouraged internationalization as a route to economic development by exploiting specialization and scale efficiencies with policies such as industrial upgrading and by allowing losers to fail. The geographic proximity of dynamic trading partners with differing comparative advantages has deepened economic integration within the region. Interestingly, East Asia’s rise is based mostly on goods production while India’s relies heavily on services, but even India has achieved 8 to 9 percent real growth rates as it gradually opens its economy.

At the same time, Asian countries are highly diverse. Unresolved historical mistrust still colours relationships with outside powers and with each other. Indeed, many Asian governments depend on partnerships with powers outside the region, particularly the United States, to insure against regional conflicts— the alliance between the United States and Japan has provided the political stability that has been a key element in East Asia’s economic rise. State-to-state relationships matter for economic success, and fledgling regional cooperative institutions are helping to manage and channel regional economic and political rivalries.

Canada, a marginal participant in this transformation, is faced on the one hand with slow growth in the United States, its main economic and strategic partner, and the concomitant growth in importance of Asia’s major economies. While economic growth in Japan—with which Canada has a century-long bilateral relationship—has stalled, total trade with the other large Asian economies has been growing rapidly. Trade with China, in particular, is driven largely by that country’s fast-growing market demand for Canada’s natural resources to feed its goods-producing industrial machine.

Yet Canada’s reputation in Asia has declined in recent years with our neglect of bilateral relationships and regional institutions. Canadians active in the region are often told that some regard us as unreliable. Canadian governments and businesses, when they turn up, make demands out of proportion to their importance and then often fail to follow through. Having invested little in understanding Asian norms and conventions, Canadians often appear to be out of step with the region’s long-term thinking and evolving relationships. Canada has no free trade agreement, now regarded as a barometer of the potential of a relationship, with any Asian country—although bilateral negotiations with Singapore began as long ago as 2001. Canada’s historically strong support for and involvement with the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has declined even as that body emerges as the main institution prodding the three giants to cooperate. Only in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum has Canada been active, but that forum has been overtaken by other institutions that are now driving Asia’s strategic integration.

Canada needs a long-term Asia strategy. As a middle power and latecomer to recognizing Asia’s potential, Canada’s objectives should be ambitious but realistic. Our history and economic geography are uniquely integrated with and dependent on the United States, but that country, even as it remains the world’s military superpower, will become a more “frugal” economic power, with protectionist pressures emanating from high rates of structural unemployment and political administrations preoccupied for at least the next decade with rebalancing the economy. Canadians cannot expect the United States to continue to provide the economic impetus we have come to take for granted. Economic integration in North America has largely stalled. Since its implementation in 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has not kept up with major structural changes—such as the rise of the Internet, global supply chains, and the service economy—or with geopolitical shifts. Even as Asian economies busily integrate, in North America security concerns thicken borders, raising the costs of cross-border transactions and obstructing the movement of professionals and technicians. Yet the current US administration has little interest in upgrading NAFTA; instead, its strategic economic interest lies in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a comprehensive agreement covering trade in goods and services and investment, which many see as a clear signal that China should not think of Asia as its back yard.

Many Canadians, however, are sanguine about these trends. After all, Canada emerged from the global financial crisis with a sound financial system, prudent macroeconomic policies and fiscal position, and strong demand for its natural resources despite a contraction in investment and net exports in early 2009. Seen another way, Canada’s sound economic base affords us flexibility in making choices about the future. Complacently continuing our heavy reliance on commodity exports and investments will neither sustain nor increase future Canadian living standards. Instead, we must modernize the secondary sector and develop new capabilities in tertiary, knowledge-based manufacturing and services if we are to compete with emerging Asian producers. Canada is also an aging society—by 2020, the median age of Canadians will be 42, compared with 37 for Americans and 32 for Mexicans. As the impetus for growth from an expanding labour force diminishes, Canadians will have to augment their reliance on extracting natural resources with innovation and knowledge that add value to those natural resources and to the production of services.

At the same time, because of history, proximity, and relative sizes, the United States will remain central to Canada’s economic future, and Canada’s Asia strategy should view the region through a CanadaUS lens. Indeed, Canada’s relationships with the United States and Asia are complementary —in some sectors, for example, our US supply chain partners export advanced intermediate goods that might have come from Canada. North America’s long-term interests will be served by deeper economic and political integration with the Asian economies. An inward-looking, more self-sufficient Asian bloc dominated by the rivalries of its three economic giants would be in no one’s interest.

Canada’s Asia strategy should also be intergenerational, in the sense of having sufficient support from the main federal political parties that its priorities and broad agenda continue to be pursued regardless of the party in power in Ottawa, and it should also take into account the provinces’ economic aspirations in Asia within the Canadian brand.

In this study, I propose the outlines of an Asia strategy for Canada. I begin by summarizing the state of play of Canada’s relationships with the United States and with Asia’s engine economies— China, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, and Malaysia—which the Asian Development Bank calls the Asia-7. I also provide some comparisons with Australia, which has had a focused Asia strategy for a generation. I then analyze sectoral patterns of trade with and direct investment in the five largest Asian economies, and draw out some implications for policy. Next, I turn to the targets and plans that China and India, in particular, have set for themselves for the coming decade, and assess the commercial opportunities of this agenda for Canada over the next two decades. In the penultimate section, I take a closer look at options for major enhancements of Canada’s economic relationship with Asia, such as joining the TPP and entering into a comprehensive economic agreement with China. Finally, I propose a strategic framework that looks out toward 2030, and offer some closing thoughts.

Canada’s Economic Relations: The State of Play

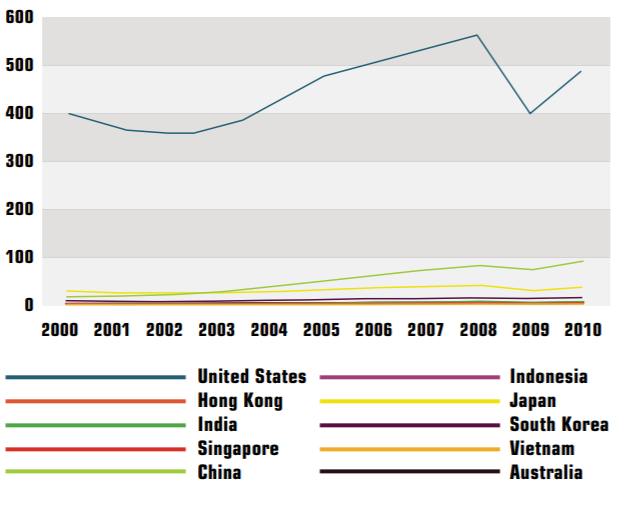

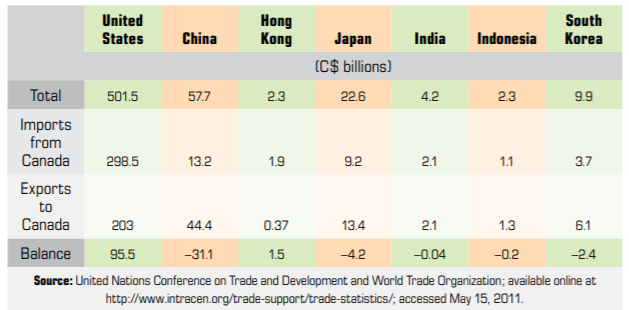

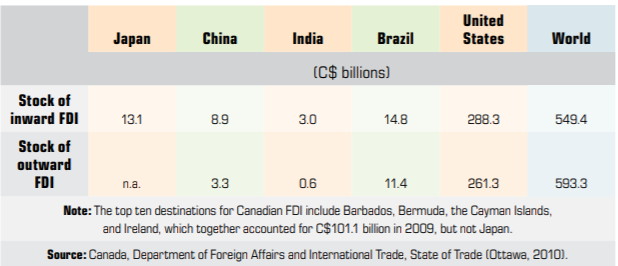

Despite the fundamental reshaping of the international economic landscape, the world’s largest trading relationship remains that between Canada and the United States (Figure 1). Indicative of the recent sea change, however, is that China is now Canada’s second-largest trading partner, though Canada-China trade still amounts to just 10 percent of Canada’s trade with the United States. Canada’s next two most important Asian trading partners are Japan and South Korea, with India and Indonesia lagging far behind. That said, in the past five years Canada’s exports to China, India, and Indonesia have grown at double-digit rates while those to the United States and the European Union have grown more slowly or even shrunk (see Table 1). Flows of immigrants and students are also significant, with China topping the list of numbers of immigrants, followed by India, Japan, and South Korea. More Canadians live in Hong Kong than anywhere else in Asia. Measured by stocks of foreign direct investment (FDI), however, the Asian economies remain well down the list as both destinations and sources, with both Japan and China trailing Brazil’s C$15 billion stock of FDI in 2009 (Appendix Table A-2), although the use of tax havens, which account for a sixth of Canada’s $593 billion total outward stock in 2009, complicate destinations of Canada’s outward investment.

For Canada, however, what stands out in sketches of the drivers of its regional and bilateral relationships (see Appendix B) is the absence of an overall strategy that recognizes Asia’s importance to Canada’s economic future. Trade negotiations are ad hoc. Consultations with private sector groups and other levels of government are ad hoc. And a robust system of national consultations focused on the national interest no longer exists, leaving these ad hoc arrangements vulnerable to capture or delay by special interests. Accordingly, Canada’s reputation in Asia has been damaged by start-stop bilateral initiatives and by what appears to others to be an exaggerated view of its own importance. Adding to the lack of a strategy that realistically assesses the importance of these major economies to Canada is the scarcity of analytic and negotiating resources. Instead, the feeling seems to be that it is pointless to allocate resources that are thin on the ground to pursue a partial agreement with, say, India, a country that, to Canadians, seems to lag far behind China in economic significance.

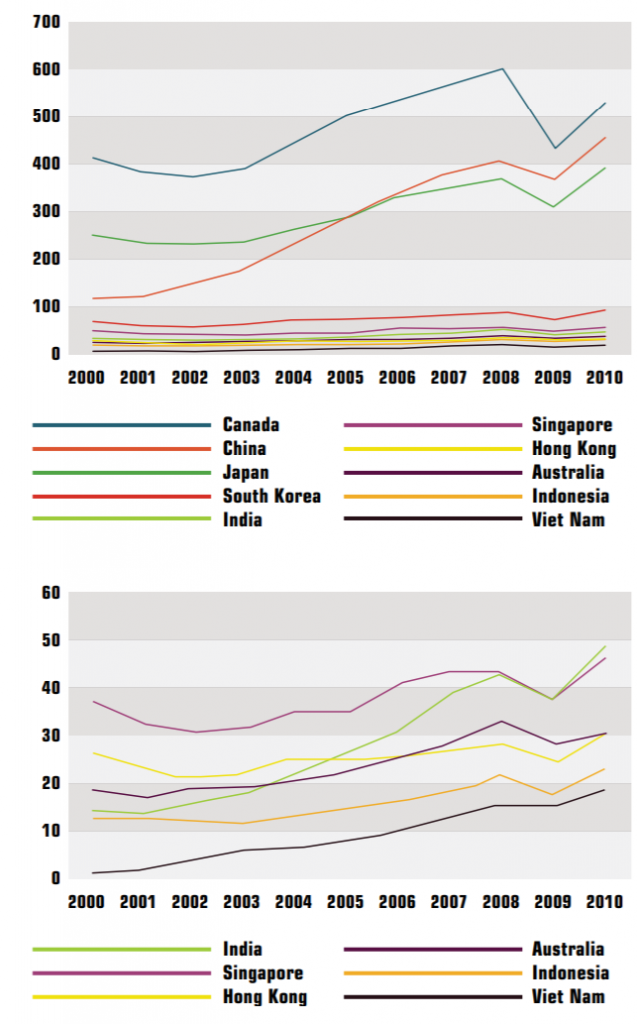

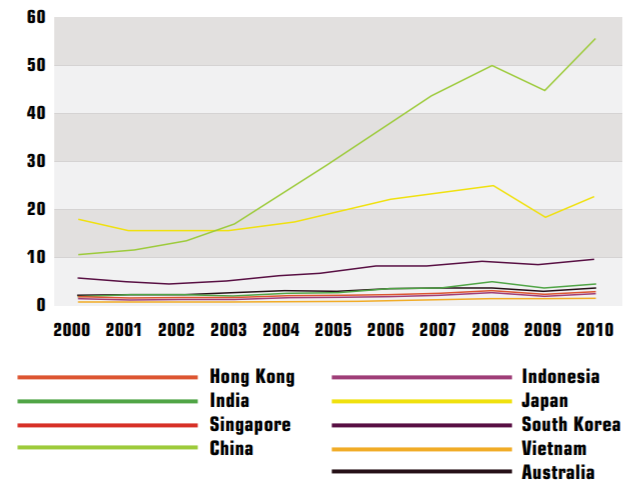

Figure 1. Total US Trade with Major Trading Partners and Selected Asian Economies, 2000-2010

Instructive here is Australia’s strategy toward Asia. Indeed, Australia has developed an influential role in the region far out of proportion to its economic size, which is a third smaller than Canada’s. More than twenty years ago, the Australian government initiated a major economic and political study of northeast Asia’s economic prospects, which painted a clear picture of the region’s potential and made far-reaching policy recommendations that were taken up at the highest level and have been sustained by successive governments of both major parties. An explicit assumption in Australia’s strategy is that its relationships with the United States, with which it has a military alliance, and the Asian economies are complementary. Australian governments also have invested heavily in maintaining personal relationships at the highest level, as Prime Minister Gillard demonstrated when she visited Japan’s prime minister following the recent devastating earthquake and tsunami. Australia has also sought to improve its diplomatic, educational, and research capabilities with respect to the major Asian economies—one target is that, by 2020, 12 percent of Australian school leavers should be able to speak an Asian language. Australia has also completed or is negotiating bilateral free trade agreements with ASEAN as a whole, with each of its more advanced members, and with Japan, South Korea, and China. It was former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd who advanced the “Big Idea” of an Asia-Pacific Community, which led to Russia and the United States joining the East Asian Summit.

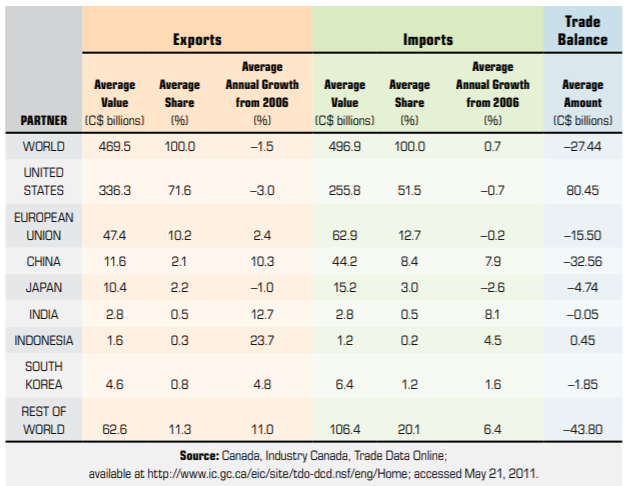

Table 1. Canada’s Diversifying Trade: Goods and Services Trade by Major Partner, 2008-2010

The Australian example thus provides a model for Canada to consider if it is serious about reviving its participation and visibility in Asia. Before considering our options, however, I first want to take a closer look at our existing relationships with the major Asia economies and to place them in the context of what the region might look like in 2030.

A Closer Look at Canada’s Economic Relationships with Asia

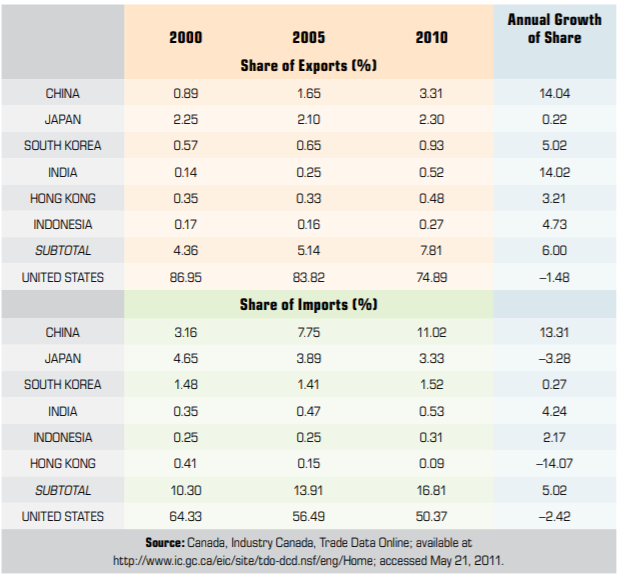

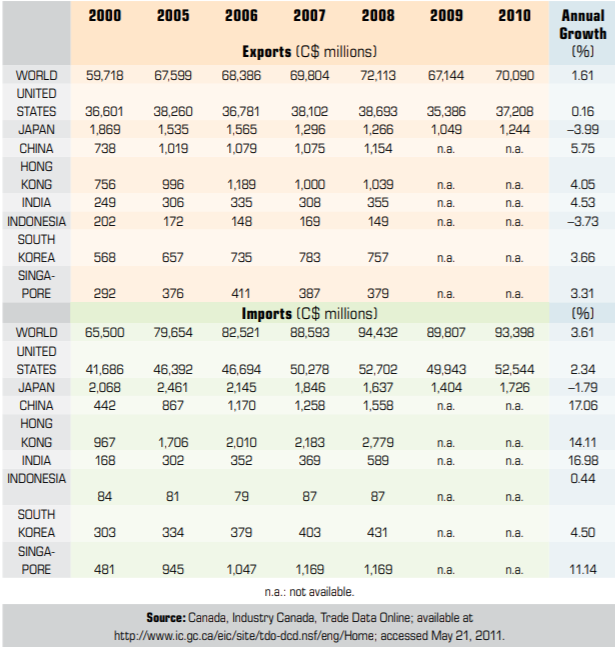

In the past decade, Canada’s trade has been diversifying beyond its historical focus on the United States and Europe and toward Asia, which is timely considering that, in 2006, China overtook Canada as the largest source of US imports. As Table 2, shows, between 2000 and 2010, Asia’s share of goods exports to Canada rose by nearly three and a half percentage points and imports by more than six points. Similar growth took place in services trade (Table 3). In both cases, much of the growth took place in trade with China— trade with Japan largely stagnated while that with India grew from a very small base. In contrast, the United States’ share of both goods and services exports declined over the decade, a trend that accelerated during the recent global financial crisis, when Canada’s trade with the United States dropped off more sharply than did its trade with any Asian partners; trade with the United States recovered smartly in 2010, but at a slower pace than that with China (Figure 2).

Table 2. Canada’s Merchandise Trade with the United States and Selected Asian Economies, 2000-10

Table 3. Canada’s Services Trade with the United States and Selected Asian Economies, 2000–10

Figure 2. Total Canadian Trade with Major Trading Partners and Selected Asian Economies. 2000-2010

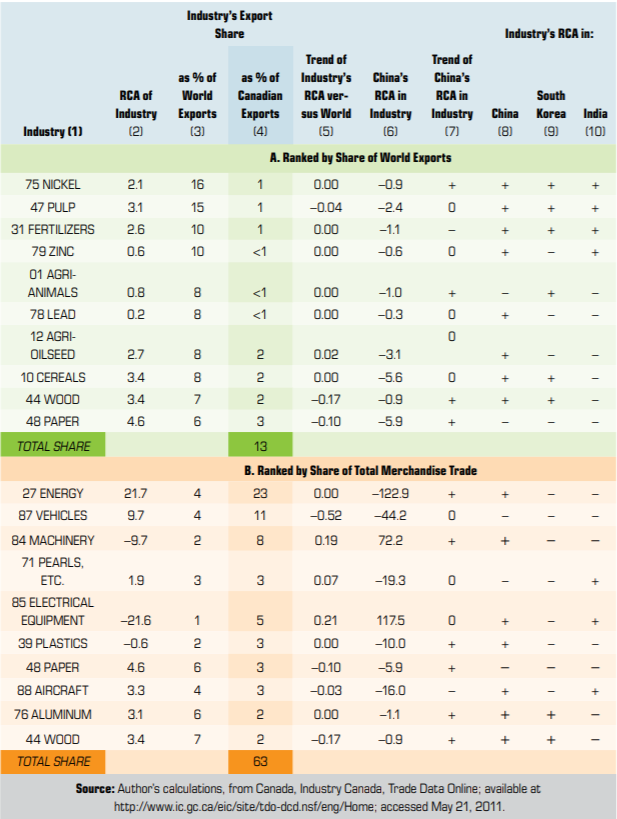

Since trade and FDI are largely market driven how does this performance accord with Canada’s evolving comparative advantage and competitiveness? In broad terms, a country’s competitiveness in merchandise trade is evaluated by comparing its exports in an industry to a particular destination with its total exports in that industry to the world at large. (Unfortunately, a similar breakdown is not available for services trade.) When exports to a particular destination exceed the global share, the measure—known as revealed comparative advantage (RCA)—indicates the exporting country’s competitiveness in that market. Table 4 compares the relative competitiveness of Canadian industries in foreign markets—including, by inference, the Chinese market—in two ways: panel A ranks those prominent in world markets by trade shares (column 3), while panel B ranks them by their prominence in Canada’s total trade (column 4). Notably, those industries prominent in world markets (panel A) account for relatively small shares of Canada’s trade, reflecting the continued dominance of the United States as a destination for Canadian exports.

The table also shows China’s relative competitiveness in world markets, measured by its RCA by industry (panel A, column 6). For Canadians, the key, and perhaps surprising, finding is that China’s comparative advantage is negative in all industries in which Canada is a world leader. In panel B we see that, with the exceptions of machinery and electrical equipment, China is relatively less competitive than Canada in the other industries. Canada is also revealed to be competitive in most of these industries in the Chinese market (panel A, columns 7 and 8, and panel B).

Table 4. Canada’s Comparative Advantage by Industry

This picture is one of complementary trade. Canada is competitive in major sectors, particularly natural resources, where China is not. The two are direct competitors in machinery and electrical equipment, and neither is competitive in vehicles. One positive sign is that the trend (column 7) in Canada’s relative competitiveness in machinery is positive, but this is offset by static trends in electrical equipment and vehicles. Canada evidently needs to increase its competitiveness in the former, while the lack of competitiveness in vehicles likely reflects, for China, its relatively low level of development, and for Canadian producers, the impact of low capacity utilization and the strengthening Canadian dollar in recent years. A number of Canadian industries are doing well in China, as a 2009 analysis by Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade confirmed. Taking into account factors such as distance, language, and formal trade agreements, the study found that Canada’s bilateral trade with China was double what would have been expected, even allowing for the high prices of Canadian commodities. Still, anecdotal evidence in industries such as construction and other services suggest Canadians are finding that competition is intensifying and that the Chinese government is according preferences to Chinese enterprises.

Several observations are suggested by these findings. Canada’s competitiveness in natural resources (panel A, column 5) is relatively static; though it is worsening in pulp and paper and wood products, these industries remain competitive in China (column 7). It is troubling, however, that Canada’s competitiveness in vehicles and aircraft appears to be declining (columns 5 and 7). Trade is largely complementary but Canada buys twice as much manufactures from China as China buys in natural resources from us; our trade deficit grew by nearly 50 percent between 2005 and 2010. Canada could close this gap by selling more natural resources to China. In the longer term, however, the solution should be to diversify bilateral trade, with Canada exporting more knowledge-based goods and services that China cannot produce, and by restoring Canada’s declining advantages in industries such as vehicles and aircraft. Now might be an opportune time for the two countries to liberalize bilateral trade since in the future both countries would benefit from a framework that facilitates specialization and intra-industry trade.

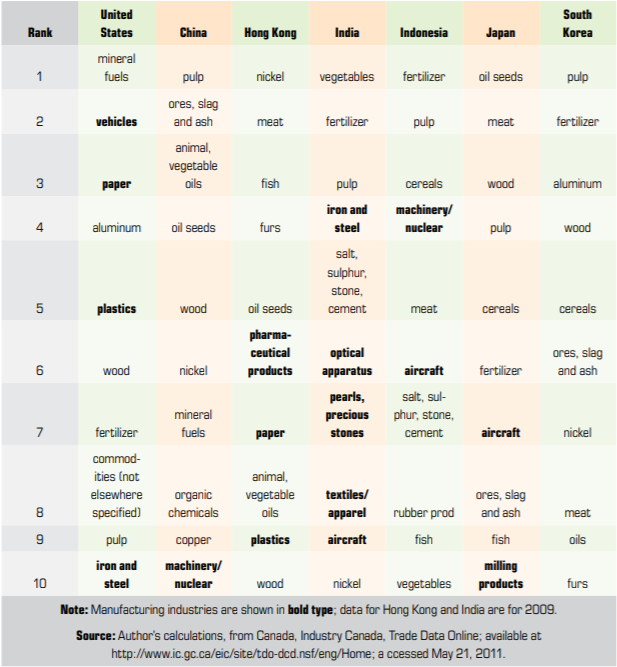

Table 4 also reveals that Canada can compete in South Korea in most of the industries in which it is a world leader. But some of the industries accounting for a large share of Canada’s total trade which are competitive in China are not competitive in South Korea. One explanation for these patterns is suggested in Table 5 which ranks Canada’s ten most competitive industries by RCA in the five largest Asian economies plus Hong Kong. None of the ten that are competitive in South Korea is a manufacturer. This is not surprising given South Korea’s success in global supply chains in goods manufacturing. Instead, natural resources, foodstuffs, and inputs to early stages of South Korean production processes account for most of Canada’s top ten exports to that country. In the other economies, too, Canada tends to be more competitive in activities further down the value chain, rather than in manufacturing (shown in bold type).

What are the policy implications of this picture for Canada? First, our competitiveness in natural resources implies that we should anticipate growing Asian interest in investing in this country in order to enhance supply. Second, the picture is confined to merchandise trade. Since regional production networks are a major feature of economic flows into and within the Asian region, policy would be much better informed if additional measures were available as to how Canadians are doing within these regional networks; these measures would include more detail on outward FDI flows which are integral to the services and sales abroad by foreign affiliates of Canadian companies. Third, although Canada’s trade diversification beyond the United States is driven primarily by Asian market demand, the size of our US trade continues to shape our competitive profile in key non-commodity industries. Are we adequately leveraging these strengths in Asian markets and supply chains?

Table 5. Top Ten Industries in which Canada Has a Strong Positive RCA in the United States and Major Asian Economies, 2010

Finally, since a major goal of the Asian economies is to move up the technology ladder, Canada has a strategic rationale for negotiating bilateral and regional trade agreements with them sooner rather than later. In the absence of such arrangements, Canada’s relative lack of competitiveness in selling manufactured goods to South Korea could foreshadow the fate of our value-added exports to, say, India, as that country’s trade patterns increasingly resemble those of South Korea in Asia’s continuing economic transformation.

Asia in 2030

Asia is on the move: this, many in the region claim, is the Asian Century. By 2030, estimates the Asian Development Bank, Asia’s middle classes will number more than 2 billion people, and trillions of dollars will have to be invested in the physical and social infrastructure they—and the aging populations of countries such as Japan and China—will demand. At the same time Asians are facing education and innovation dilemmas: while large investments in education are being made in both China and India, these are producing millions of college graduates alongside serious shortages of technical and scientific skills.

Asia is also rapidly urbanizing: by 2020, it will contain 13 of the world’s 25 largest metropolises, each with more than ten million people. And Asia is integrating, as major investments are made in transportation routes to facilitate intra-regional trade. Asian enterprises are also moving up the rankings of the world’s largest firms and financial institutions: in 2010, 23 of the top 100 of the Fortune Global 500 by total revenues were Asian, 11 from Japan, 6 from China, and 3 from South Korea. Enterprises such as Samsung Electronics, Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Tata Motors, CITIC, Cosco, and the national oil companies of China and India are among the world’s major outward investors. Indeed, the single largest determinant of rising world prices for oil and other natural resources is incremental Asian demand.

As Asians increasingly “think Asian,” two things are happening. First, Asians are creating their own regional institutions in security, finance, and trade—and inviting the United States to join. For years the Asia-7 followed export-led development models that focused on final markets in the advanced industrial countries. India and its dynamic service sectors aside, most East Asians participate in regional production networks organized around Chinese assembly platforms. These regional networks proved to be a doubleedged sword in the global financial crisis when export demand in final goods markets evaporated, a shock that cascaded through Asian supply chains. The wakeup call prompted East Asian governments to shift their growth strategies toward regional and domestic demand—to a heavier reliance on other sources of growth, such as services and improved productivity, to replace low-cost manufacturing.

Second, Asians are coming to terms with slower economic growth. Unthinkable before the global crisis, slower growth now seems inevitable as social and political tensions rise over the side effects of rapid industrialization, rising income inequality, and environmental degradation. Sustaining economic growth through productivity increases and innovation, which require institutional change, is proving a challenge. In the decade ahead, we can expect growing pressures on Asian policymakers to improve income distribution and services, particularly those that fulfill middle-class aspirations for housing, health, education, financial security, and environmental quality.

China and India

What will massively populated China and India look like by 2030? In the short term, both are struggling with widespread corruption and persistent inflationary pressures. Beyond that, growth in the five-year economic plans of both countries (coincidently the twelfth for each) is headed in opposite directions. China’s plan for 2011–15 is to moderate the economy’s growth rate and undertake a major restructuring, while India’s plan for 2012–17 aims for 9–10 percent economic growth to generate jobs and promote social inclusiveness. Both will undoubtedly be preoccupied with these goals far into the future.

China intends to rebalance its economy to rely more on growth in household consumption and less on heavy investment in industrial export-oriented production. It is also shifting production and development to the inland regions. It intends to boost consumption by, for example, increasing the minimum wage, spending more on the social safety net and social housing, and pushing for even more urbanization—Chinese cities are expected to grow by 300 million people over the next 30 years. China is also encouraging greater private sector participation in the labour-intensive service industries through deregulation and making financing more accessible for small and mediumsized business. Innovation and productivity growth are also part of China’s rebalancing strategy, with the targeting of seven emerging “pillar” industries, three of them “green”: renewable energy sources, energy conservation, new energy (electric cars), biotechnology, new materials, advanced manufacturing (including high-speed trains and aerospace), and new-generation information technology. The plan calls for energy prices to be determined more by market forces than by government fiat, and for carbon emissions to be taxed. The large industrial state-owned enterprises will pay higher dividends to their central government owners, and a planned value-added tax will cede more tax room to local governments, which have had to rely heavily on revenues from land sales.

In contrast, Inidia’s five year plan is more indicative and aspirational because of the diffused nature of power in India’s federal structure. The five year plan places greater emphasis than in the past on greater market efficiency, innovation, and energy—in the latter two areas, India is already a leader in the developing world. India is also focusing on education, transportation, and urbanization—cities are to retain a portion of the new national value-added tax to help with their finances. India’s political diversity, however, makes it uncertain whether the country can reach its economic potential without determined efforts by the dynamic private sector. Some states, like Gujarat, approach developed-country levels, while populous northeastern states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar lag far behind. Product market reforms have not been matched by labour market reforms. Over the next twenty years, India will have to absorb 250 million 15-to-24-yearolds into the labour force—yet 90 percent of Indian employment is casual, devoid of benefits or skills training. Opposition from powerful interest groups is slowing the pace of domestic reform and hampering liberalization of investment and trade, both of which are neeed to maintain India’s growth momentum in the years ahead.

Risks and Uncertainties

Slower growth: As middle-class consumption assumes greater importance relative to investment growth in the more advanced East Asian economies, slower growth will mean more intense competition among foreign exporters of natural resources, like Canada, and more production opportunities in the developing economies such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam to which labour-intensive manufacturing is shifting.

Declining saving rates: One outcome of aging and rising consumption among Asian populations—with increasing demands for residential, infrastructure, and productive investment—is declining rates of household saving. A recent McKinsey forecast of the supply of and demand for investment in physical capital in Asia out to 2030 predicts a growing shortfall of the supply of capital and higher capital costs.

The middle-income trap: Rising expectations by those aspiring to middle incomes could lead to rising political tensions as Chinese and Indian governments struggle, without the necessary institutional structures, to address regional and income inequalities. Some worry that pushback from powerful vested interests will cause growth rates to slow and per capita

incomes to stagnate, known as the middle-income “trap”, that will be difficult to escape. India’s political leaders, even when holding a parliamentary majority, have failed to carry out targeted job-creation reforms, and the Indian parliament is paralyzed by corruption scandals. China faces persistent inflation, while strong political pressures oppose solutions such as exchange rate appreciation. The country also faces the challenge of a major leadership transition over the next few years.

Business Opportunities for Canadian Firms

Despite the challenges China and India face in the years ahead, their economic plans offer opportunities for Canadian businesses, particularly in areas such as agriculture, natural resource commodities, energy, and the environment (including so-called clean technology and greener urbanization), and in services such as health care, education, entertainment, and tourism for which demand by middle-class Chinese and Indians is rising.

The environment: China’s quest for cleaner energy has moved beyond ambitious plans for nuclear generation to a desire to pursue new sources such as wind, solar, biomass, coal-bed methane, and shale gas. As well, China’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions has triggered a wave of activity in clean technologies, including smart grids, carbon capture and storage, and battery storage technologies. These priorities will create major opportunities for Canadian firms in energy and other consulting services that assist, for example, in the design and expansion of conservation activities.

Health care: By 2030, China is expected to have 300 million people of retirement age, and they will be demanding better health care services than are provided today—China’s rising middle classes are already creating demand for high-end medical and health care services—opening opportunities for foreign partnerships in medical research and medical equipment production.

Urban services: By 2030, more than a billion Chinese and 600 million Indians will live in cities, making the quality of urban life a major issue in both countries. Both have ambitious plans to increase energy efficiency, mass transit infrastructure, and water treatment and sanitation facilities, although India faces major challenges in these areas, particularly in its burgeoning second – and third-rank cities.

Services for the middle classes: Fast-growing middle classes in both countries are demanding better services not only in health care, as noted, but also in areas such as higher education and financial services. Affluent Chinese are demanding access to financial institutions to manage their crossborder transactions, while the rising international presence of Chinese companies is increasing demand for underwriters and investment banking services. China’s capital market is much less developed than India’s, except in the issuing of corporate bonds, while privately owned corporations in both countries still face heavy restrictions on bond financing.

Tourism: The increasing affluence of middle-class Chinese and Indians is expected to boost their demand for foreign travel significantly. China has already granted Canada “approved destination,” opening new opportunities for Canadian travel services as more Chinese nationals visit this country.

New technologies: China’s targets for biotechnology and nanotechnology as areas for breakthroughs in basic research signal a larger set of educational opportunities. The state has planned a total investment of US $20 billion in biotechnology by 2030, while nanotechnology received some of the US$50 billion allocated to research and development funding in the 2008 stimulus package. Many of these resources have been allocated to the large universities and research centres, but smaller centres have also benefited and it is there that universities and firms are more open to foreign collaboration and to educational opportunities encouraged by local governments.

Outflows of Chinese capital: As domestic growth slows, both state-owned and and non-state enterprises will seek to expand abroad. Profitable state-owned enterprises will want access to natural resource assets, new markets, brands, and technologies. Despite the high profile of Chinese FDI in the United States, its total is still less than that of South Korea, Brazil, or India. That, however, will change. The New York-based Rhodium Group estimates that, if China’s outward investments were to follow a trajectory similar to Japan’s in the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese investors would invest US$1–2 trillion abroad in the next decade, with much of it headed for the United States. Canada currently receives 75 percent as much Chinese FDI ($9 billion in 2010) as the United States ($12 billion); were that ratio to continue, hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese investments could be headed for Canada.

The Implications of Asia’s Rise

By 2030 Asia could be at the centre of global economic gravity. If the region is to achieve sustained growth, however, it will have to depend more heavily on productivity growth and on domestic and regional demand. How far this rebalancing proceeds in the coming decade depends on the political will to address interests vested in the entrenched export-led growth model.

In adapting to this economic gravity shift, Canada has many distinctive competitive advantages. It is the world’s largest producer and exporter of uranium and potash; the second-largest producer of nickel, wheat, and hydroelectricity; and the third-largest producer of natural gas, diamonds, and renewable fresh water (of which it has 7 percent of the world’s total). Its cities are attractive and work well— the World Economist Liveability Index ranks Vancouver, Toronto, and Calgary among the top ten most liveable cities in the world. Canadian-based firms compete globally in construction and infrastructure development; Canadian public pension and social security arrangements are sustainable; and its financial institutions are strong.

Canadians can leverage these strengths in imaginative and forward-looking ways to help Asians meet the challenges of education that encourages creativity and innovation; access to natural resources; the development of alternative energy sources, liveable cities, and reliable infrastructure; and growing middle-class demands for modern services.

Enhancing Canada’s Asian Economic Ties

The importance of state-to-state relationships means that the reliable and transparent frameworks in which Canadian businesses respond to these opportunities cannot be built without comprehensive bi – or multilateral economic agreements. Two options are of particular interest: joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership and pursuing a deeper economic relationship with China— both potential game changers for Canada and by no means mutually exclusive.

Joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership

The TPP aims to be a comprehensive, high-quality free trade agreement open to any economy around the Pacific—a geographic notion that, in this case, even includes India—that accepts the agreement’s ambitious goals. The TPP had modest origins, beginning life in 2006 as an agreement among Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore. The so-called P4 found the agreement relatively easy to negotiate because of their complementary economic structures. Significantly, they established a mechanism for other countries to join—Australia, Malaysia, Peru, and Vietnam have done so, Japan has signalled its interest, and South Korea could follow when the US Congress ratifies the US-South Korea free trade agreement. The United States joined the TPP in 2009, considerably expanding the negotiations to include financial services and investment, which had been deferred in the initial agreement. The Americans also complicated the talks by introducing “NAFTA Plus” issues such as the environment and labour, government procurement, and intellectual property enforcement—particularly on pharmaceuticals and copyright issues—and by arguing for the use of sanctions against violators. The TPP does not affect any country’s commitments under the World Trade Organization (WTO), but free trade agreements already in force—for example, those between the United States and, separately, Chile (2003), Singapore (2004), and Australia (2005)—may be upgraded as part of TPP negotiations.

For many Canadians, however, the idea of hitching their economic wagon to rising Asia is still below their radar. Most remain unaware of the TPP, and yet the partnership could be a game changer, for several reasons. First, its inclusion of services and investment offers a way to address NAFTA’s deficiencies in services, regulatory harmonization, and investment. Second, the TPP’s broader reach and multiple negotiating partners could increase opportunities to make the tradeoffs that are a vital part of any comprehensive agreement. In Canada’s case, it would have to be willing to discuss intellectual property protection and agricultural supply management, areas where it is viewed as behind global standards. In this, Canada would not be alone—other participants, not least the United States have agricultural issues. Australia and New Zealand successfully rationalized their own supply management programs by abolishing subsidies (in New Zealand nearly 30 years ago) and by buying out farmers (in Australia). Agriculture has been a sensitive issue for Chile as well, but it has agreed to phase out its tariffs by 2017 using safeguards during the transition period to protect the dairy industry. How long can Canada’s archaic system hold the national interest hostage? The TPP provides a golden opportunity to phase out such programs in return for concessions in other areas, from the United States and others.

It is still too soon to say if the TPP talks will achieve their goals. At the seventh round of talks in June 2010 in Vietnam, participants agreed to submit negotiating frameworks for major sectors— including goods and services, intellectual property protection, FDI screening, government procurement, and standards—to their leaders in November 2011, around the time of the APEC summit in Honolulu. To the extent they succeed, they will have established baselines for future participants that will be difficult to change. Part of the long-term payoff for the United States will be to extend the TPP to its larger trading partners, including Canada, but Canada’s continued preference for supply management programs remains a significant obstacle to our participation. If we cannot or will not join TPP, then the fallback position could be the negotiation of a series of economic framework agreements with priority countries in Asia, or with some other regional Asian arrangement.

Deepening Canada’s Economic Engagement with China

For Canada, another possible game changer is to pursue deeper economic ties with China. On the face of it, a bilateral negotiation should be straightforward since trade between the two countries is complementary: China exchanges its consumer goods for Canada’s natural resources. In the short term, the potential benefits would come from enlarged markets and economies of scale as well as reduced transactions costs. Through time, further benefits would follow from specialization and the growth of intra-industry trade as the Chinese economy evolves. China already has pursued free trade agreements actively both within Asia and beyond. It has agreements with Chile, New Zealand, Peru, and Singapore (all participants in the TPP), as well as Costa Rica, Hong Kong and Macao, Taiwan, Pakistan, and Thailand. In January 2010, China implemented an agreement with ASEAN, and further negotiations are under way with Australia, Iceland, India, Mongolia, Norway, South Africa, and South Korea, as well as with ASEAN+3, ASEAN+6, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Any Canada-China talks should aim for an agreement that is consistent with WTO rules and broadly based, including tariffs and non-tariff barriers and other obstacles to services trade and investment. China maintains tariffs in a number of areas, particularly in industries such as rice, meat products, processed foods, textiles and apparel, and vehicles and parts. On Canada’s side, 68 percent of tariff lines are already tariff free, but tariff-rate quotas still exist in supply-managed products, beef, and wheat. Both countries likely would gain from tariff reductions on principal exports; for Canada, these would come from agricultural, mineral, and services exports, while China would gain from expanded agricultural exports.

Transportation and travel services, rather than commercial services, dominate the two countries’ bilateral services trade, and should be an important part of negotiations—services account for 70 percent of Canada’s GDP and are gaining significance in China as well. Services trade in China faces impediments, however. In addition to a tariff on the services sector (estimated to be around 9 percent in 2004), state trading enterprises, which exercise market power to collect monopolistic rents, play a significant role. Other well-known impediments include ownership and licensing restrictions, weak enforcement of intellectual property rights, lack of administrative transparency, and discriminatory procurement practices.

China would also demand that Canada accord it market economy status (MES). In its WTO accession talks, which concluded in 2001, China was designated a non-market economy, but it will acquire MES automatically after 15 years—that is, on December 31, 2015. Early recognition of China as a market economy is also an issue in its ongoing dialogue with the United States. As the clock ticks toward 2016, however, the value of such early recognition is declining.

What are Canada’s prospects of success if it were to plunge directly into free trade negotiations with China? China has had such negotiations with three other developed economies, and the record is instructive. Those with Australia are stalled: China remains reluctant to address Australia’s interests in liberalizing services trade and agriculture, while differences exist over China’s interests in people flows, its protection of intellectual property rights and Australia’s rules on FDI. Talks with Norway are also at an impasse, and despite its completed agreement with China, New Zealand has encountered discriminatory behaviour toward its dairy exports. This record suggests that, for Canada, moving directly toward a comprehensive bilateral agreement might not be the most productive choice. More promising might be to negotiate a series of confidence-building agreements structured to deliver liberalizing momentum as they enter into force, and to create a framework for future talks as China’s comparative advantage changes.

A Proposal for a Canadian Asia Strategy

To understand why Canada needs an Asia strategy, we need look no further than Canada’s surprising failure so far to complete a free trade agreement with any Asian country. Talks with South Korea are stalled by auto and beef interests (Canada excepted supply management even before the talks began). Talks with Singapore are stalled by unrealistic demands for concessions equal to those given to the United States. And, as noted, Canada’s policies on supply management and intellectual property are blocking its participation in the TPP. In each case, short-term domestic political considerations are outweighing the economic calculus of the national interest.

This ad hoc approach is risky and short sighted. It invites everheavier reliance on developing and exporting natural resources and energy to sustain Canadians’ living standards, and, as Asian economies determinedly move up the value chain, Canadian nonresource-based industries will find it increasingly difficult to compete. Canadians need to think again about how to seize the opportunity and strategically re-engage with Asia, starting with determining what we want and how we should achieve it. Instead, Canada sits on the sidelines—a policy taker. To have a voice, Canada has to show up, to become involved in collective approaches to political and economic development that serve its deep interests in open markets.

Canada’s strategy toward China should be an integral part of its strategy toward Asia in general—the two should be mutually reinforcing. Canada’s goals in formulating an Asia strategy should be to promote cooperation with the Chinese where feasible and to reassure those who are concerned about an exclusive focus on China. China recognizes the value of multilateralism, not just because it used its accession to the WTO to restructure its economy and enter world markets, but because these institutions provide a way to pursue its objective of restraining US hegemonic behaviour.

Within this strategic framework, there are at least five criteria to consider in choosing among alternatives and setting policies. First, the Asia strategy should be generational and serve Canada’s long-term national interests; framed in this way, the strategy should, like deficit and debt reduction, be followed through by successive governments regardless of political stripe. Second, the strategy should focus on the largest of the Asia-7 players, which will have the greatest effect on our economic future. Third, it should aim to solve the difficulties Canadian businesses face in the region’s distant and unfamiliar economies through improved market access and greater participation its production networks. Fourth, the strategy, recognizing that Asia’s dynamic economies will move up the value chain, should pursue technological collaboration that helps address Canada’s weak productivity performance and builds potential complementarities. Finally, any Canadian Asia strategy should be sensitive to US interests—though Canadians might not realize it, strong moves to diversify the markets for our energy and natural resources will have geopolitical significance.

Elements of the Strategy

Restore Canada’s presence in the region

State and high-level personal relationships are essential to the confidence and trust on which long-term agreements are built. Canada has been active in APEC, but that body no longer drives regional integration and we have been slow to seek membership in the next generation of institutions. At the apex of these is the East Asian Summit, but with the recent addition of Russia and the United States, some are pushing to close its membership, which would leave Canada out. Canada’s minister of defence has participated only once in the nine meetings of the Shangri-La Dialogue, the region’s leading security forum, while US and Chinese officials at the highest levels ensure they have a voice in the new regional architecture. Canada’s inaction in such matters signals that it is concerned only about bilateral relationships—a serious misreading of Asia’s evolving architecture. It is not yet too late, however, and Canada should begin by endowing the ASEANCanada Enhanced Partnership (2010–15) with sufficient resources and personnel commitments to realize its intended educational exchanges, dialogues on institutions, trade and business, the environment, crime, and new technologies. With that engagement as a building block, Canada then needs to pursue other options, including applying to join the East Asian Summit and participating in security dialogues and in both ASEAN-related activities and their regional and trans-Pacific counterparts. These initiatives are more likely to be successful if Canada identifies and builds relationships with economies—Indonesia and South Korea, for example—whose governments might be willing to serve as entry points to Asian regional institutions.

Develop the Canada brand

Canada should develop itself as a brand, both at home and in Asia. At home, the proclamation of a Year of Canada and Asia would help build public awareness of the importance of that part of the world for Canada’s economic future. In addition to federal government participation in Asian institutions, governments and other interests within Canada should also be encouraged to become involved in the Asia strategy. For example, Ottawa should engage provincial premiers in developing an integrated approach to Asia, one that sees them coordinating their Asian travels and aligning their policies in their areas of jurisdiction, including include health, education, and even FDI. Business groups and trade associations could publicly showcase companies with successful business strategies in the region and work to encourage visits to Canada by Asian tourists. Canadian universities should build on the country’s growing reputation as a place in which to become educated—already, international students are estimated to spend more than C$6 billion annually studying in Canada, 40 percent of it by Chinese and South Korean students. Universities and other educational institutions should also cooperate in developing channels through which young Canadians can create businesses in Asia or find employment in enterprises located there.

In short, Canadians should begin to think of Canada as an Asian location, linking world-class expertise in research and business development across borders. Signs of this sea change are already evident: Calgary is pursuing a global hub strategy for non-conventional petroleum and alternative energy development, Montreal is an aerospace and pharmaceuticals hub, and Toronto aims to become an international financial centre. As McKinsey’s Dominic Barton points out, Canada is well positioned to become an education hub for Asia, a hub for Asian multinational enterprises in the Americas, a major tourism destination for Asians, and a supportive jurisdiction for water-intensive industry and green technology. All these advantages should be drawn together in developing the national brand.

Ambitious targets are also needed. With export growth rates to major Asian economies ranging from 5 to 24 percent over the 2006–10 period, Canada could aim to double the value of its exports to Asia by 2015. The level of Canada’s outward FDI is more difficult to target since it depends on the strategies companies adopt, but to the extent that inbound FDI is determined by Canada’s regulatory regime, a transparent, best-practice review process should be in place by 2012.

Liberalize trade and investment

Canada should focus on trade deals as the centrepiece of any long-term strategy with respect to Asia. So far, it has a number of foreign investment promotion and protection agreements (FIPAs) with smaller Asian economies but none with the giants. At the very least, Canada should try to qualify for entry to the TPP talks, which would send a strong signal of our renewed commitment to Asia and allow us to accomplish market access objectives with several participants at the same time. Skeptics who doubt that the United States, in the end, will make concessions in sectors such as agriculture consider Canada’s exclusion from the TPP-9 negotiations a mixed blessing. But what are our options if the United States remains committed and South Korea and Japan join the talks?

Barring access to TPP, economic framework agreements in priority countries may be needed to unlock the benefits for Canadian business in Asian economies. This means liberalizing the movement of people, capital, goods and services in a comprehensive manner, including in areas such as regulatory cooperation, logistics, intellectual property, investment, rules and standards, competition, recourse, science and technology, the mobility of academics and professionals, etc.

Create a China roadmap

A key element of a Canadian Asia strategy should be to create a roadmap for our developing relationship with China. Indeed, one of the benefits of a higher Canadian profile in the region would be the forming of linkages that help us make our way in China—a good example is Foreign Minister John Baird’s July 2011 visit to Beijing en route to the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meetings in Indonesia. The end result, though, should be a comprehensive economic agreement between the two countries. The first steps toward such an agreement have already been taken, through bilateral agreements in transportation, financial information, science and technology, marine and fisheries management, and the environment. China’s interests include education, people flows, access to energy and natural resources, and food security, which it is pursuing through enhanced trade and investment. It also seeks recognition of its market economy status earlier than the automatic WTO procedure at the end of 2015. For its part, Canada seeks access to Chinese markets for goods and services. Small and medium-sized Canadian businesses would benefit from access to Chinese global supply chains, and Canada needs Chinese capital to develop its infrastructure and natural resources.

FDI tops the list of bilateral economic issues. Talks on a FIPA are stalled. China’s recent formalization of regulations for reviewing foreign acquisitions on national security grounds lack detail on how they will be applied and how they will interact with the established FDI and antitrust review process. On the other side, Chinese investors, like other foreign investors, consider Canada’s investment review framework uncertain and lacking in transparency—its net benefit test seems both subjective and unpredictable. Canadians, for their part, are uncertain about the future behaviour of China’s state-owned enterprises, huge oligopolies or monopolies with close ties to government owners and regulators and unfamiliar with international rules of the road and market-based regulatory regimes in host countries. Canadians worry that majority owners make decisions on political, rather than commercial, grounds. To address these worries, a transparent national interest test should apply to both foreign-owned entities and domestic firms under similar circumstances.

As China’s growth slows in the years ahead, Canada should prepare for a torrent of Chinese FDI. But it also needs to send a clear signal that FDI is welcome, and that the FDI review process will be fair. Canadians also need to understand the motivation and governance of Chinese enterprises that invest in Canada. To that end, trade associations, educational institutions, and business partners could contribute by sharing positive experiences. But we also need to be realistic in our expectations of China’s corporate governance practices. We should encourage greater transparency, but we should not expect China to change overnight. Putting our own house in order probably is the key to a successful FIPA.

There is evidence that China understands Canada’s openness as an investment destination, even in the sensitive resource and energy sectors. China has invested in Alberta’s oil sands resources and in other long-term initiatives a total of $15 billion in the past 18 months. Also, the China Investment Corporation has chosen Toronto for its first overseas office. The roadmap should address China’s intellectual property protection and government procurement practices, as well as its licensing and ownership restrictions on foreign service providers, instruments China is using to promote its indigenous innovation goals. China also has yet to join the WTO government procurement agreement. With the Doha round of multilateral trade talks stalled, Canada should be pushing these issues on a bilateral basis; as a quid pro quo, it could offer early recognition of China as market economy. Given the relative size of our economy, we will have to work more closely with other countries to achieve progress or reciprocity in these areas.

The road map also should cover private sector activities. Canadian business leaders and other stakeholders should be part of highlevel delegations to China, and they should focus on penetrating sectors in China that are expected to grow in the years ahead, These include consumer products, which are facing increased competition and logistics challenges as well as rising input costs; health, education, financial services, and logistics industries, which are slated for deregulation; and financial institutions, which are struggling to meet rising Chinese middleclass demands for wealth management services and which lack the risk management capabilities necessary to finance small and medium businesses. Infrastructure investment will expand in rural areas and greener urban centres. Mature manufacturers will face requirements to increase efficiency through consolidation and innovation. All of these industries will encounter skills shortages that educational services, imported from Canada, could help address. The value of Canada’s exports of educational services to China is already substantial—an estimated $1.9 billion in 2010—but the potential is considerable.

Enhance the Canadian business presence

Canada is distinctive as a country of small and medium-size firms: in 2008, between 80 and 90 percent of Canadian companies were that size and they were generating half of Canada’s GDP. These firms are at the forefront of those entering markets in non-OECD countries and account for nearly half the value of Canada’s exports to those countries. Yet, what do we know about the most common barriers and constraints they face? For example, is small size a problem for Canada’s successful services firms and goods exporters? This matters, because their potential customers and partners in Asia are likely to be very large enterprises able to take advantage of scale economies far beyond the capabilities of smaller Canadian firms. Asian markets are also distant and unfamiliar, leading to higher transactions costs for smaller firms. We need innovative ways to overcome these barriers: perhaps a Canadian ship, anchored in the harbour at Hong Kong or Shanghai, serving as a networking base to help smaller Canadian firms reduce their costs in these markets. Canadian governments and trade associations also should cooperate on an action plan and engage in regular consultations around such goals as supporting the greater penetration of Asian markets by small and medium-sized firms. One example would be to develop mentorship programs involving business people with real experience working in Asia.

Anticipate the future

Given the commitment of Asian economies to move up the technology ladder, Canadians can expect that bilateral economic relationships will become less complementary and more competitive in future. Our lagging productivity performance relative to our US neighbours—Canada’s business sector output per hour is less than 80 percent that of the United States—gives some indication of the challenges this implies. There is no silver bullet with which to improve productivity performance, but measures relevant to an Asia strategy include increasing competition in the domestic Canadian market through greater openness to international markets; increasing both competition and cooperation among small and medium-sized enterprises and large firms within national clusters and across borders; enhancing the ability of Canadian financial institutions to support risk taking; improving the protection of intellectual property; setting national learning goals; and developing imaginative ways to nurture young innovators.

Canada also should aim to encourage the growth of an independent cadre of Asia experts in its research and educational institutions. Over the years, a number of centres have developed on an ad hoc basis in response to particular political interests. These resources now need to be rationalized into a network of recognized business, economic, and security expertise. Also as part of an Asia strategy, provincial governments should encourage the study of Asian languages in secondary schools, as Australia is doing.

In conclusion, a long-term strategy toward deepening Canada’s economic relationship with rising Asia should include ambitious targets that require bold leadership and the participation of Canadian partnerships at all levels. It should be multi-faceted, with regional, bilateral (Canada-US) and security dimensions. It should include a new commitment to Asia’s evolving and increasingly significant institutional architecture. And it should include preparations at home to meet future Asian competition. Such a strategy cannot be built overnight, but we must begin: the potential returns to Canada are high, and so are the costs of an inadequate Canadian response to the evolving multipolar world.

Appendix A

Table A-1. Canada’s Merchandise Trade with the United States and Selected Asian Economies, 2010

Table A-2. Inward and Outward Stock of Canada’s FDI, Selected Countries, 2009

Appendix B: Thumbnail Sketches of Major Economies and Institutions

The United States

Canada’s trade flows with the United States have been slowing (Figure 2) as that country tightens security and the scrutiny of crossborder transactions and movements of people. The stronger Canadian dollar, structural changes in the auto industry, and growing competition from Chinese suppliers compound the effect. At the same time, NAFTA, which is mainly about goods and limited in its treatment of services and FDI, has become outdated. For many services producers, the “tyranny of small (regulatory) differences” in the two countries raises transactions costs unnecessarily. NAFTA’s rules of origin have become an irritant as US bureaucrats tighten their application; indeed, businesses find it cheaper to pay the tariff than to comply with the rules. Even so, autos, steel, energy, and finance are becoming increasingly integrated into regional production networks, with business segments located where production is most efficient. Technology is gradually moving clearance procedures away from the border for cargo movements in cross-border supply chains in the auto industry, and for low-risk travellers, incremental change remains the order of the day.

A decade after the events of 9/11, the border is still a central issue. Indeed, rising transactions costs act like a tariff, just the opposite of what the free trade negotiations intended. “Smart border” initiatives are a bilateral priority in Beyond the Border negotiations and at the Regulatory Cooperation Council. But there should be no illusions. These are pragmatic

incremental initiatives that do not address the central strategic issue: the trade gains from NAFTA have been realized, and there is no US interest or internal pressure to modernize the agreement on a stand-alone basis. The Obama administration is interested in friendly and productive economic relationships with the next-door neighbours, but its preference is to manage the status quo. US trade policy is focused on passing the completed free trade agreements with South Korea, Colombia, and Panama, and working on the TPP.

The United States’ goals are primarily strategic. They are, as US Trade Representative Ron Kirk has explained, “to create a potential platform for economic integration across the Asia-Pacific region” and to expand US exports and promote US interests with the world’s “fastest-growing economies.” While the initial TPP negotiating partners are a group of “like-minded countries that share a commitment to concluding a high-standard trade agreement,” US participation is “predicated on the shared objective of expanding this initial agreement to additional countries throughout the AsiaPacific region.”

The number one economic issue in the United States, however, is the slowness of the recovery from the near-depression of 2008–09, continuing high unemployment, and the parlous state of public finances at both the state and national level. Increasing exports is seen as a new channel for job growth as the US dollar depreciates.

China

China is Canada’s largest overall trading partner in Asia, with total goods trade nearing C$58 billion in 2010. At the end of 2009, direct investment stocks in each other’s economy stood at C$4 billion for Canada and C$9 billion for China. People flows are significant: the Chinese diaspora, at an estimated 1.3 million people, is Canada’s largest, and China tops the list of Asian countries of origin for immigrant flows, which averaged 33,000 a year between 1998 and 2007, many of whom arrived with a university degree.

In 2009, China became the world’s largest exporting nation, accounting for 10 percent of the total. Its major trading partners are Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and the United States. After three decades of near-double-digit growth, China passed Japan in 2010 to become the world’s second-largest economy and is expected to eclipse the US economy in size sometime in the next twenty years. The speed of this ascendancy has created dilemmas, both for China and for the rest of the world. In per capita terms, most Chinese are still poor. Chinese policymakers continue to have a “small country” mentality, thinking primarily in terms of China’s domestic interests, while the rest of the world sees a large economic dragon whose every move affects its neighbours and beyond. Chinese decision-makers are under increasing pressure to be “responsible stakeholders” who consider collective global interests in domestic policymaking. China’s re-emergence as a major economic power is complicating its relationship with the United States, which Chinese leaders still see as a model of dynamism and a reliable place to invest China’s growing wealth. In the coming decade, can the two governments cooperate even as their interests often conflict?

Yet China has major domestic challenges. The dash for growth has caused rising social tensions, growing regional and income inequalities, environmental degradation, and diminishing marginal returns to export-led industrial growth. China’s 12th Five Year Plan (2011–15) has shifted the focus toward greater emphasis on household consumption and services. As domestic growth slows in China, Canada should expect to see rising interest in its markets, brand, technologies, and natural resources on the part of Chinese investors.

Although Canada was early among western countries in recognizing the communist regime, its relationship with China deteriorated over the past decade, in part because of a very public focus on human rights issues. Though a more balanced approach has since been established, continued high-level engagement between governments will be particularly important in light of the strong role the state plays in many aspects of Chinese economic life. Already, Canada and China have a series of bilateral agreements on air services and maritime transport, financial information services, and cooperation in science and technology, as well as a Memorandum of Understanding on environmental cooperation. More recently, the two governments have assigned officials to a Joint Economic and Trade Committee that is studying sectoral complementarities and options for formalizing the economic relationship. Assisting this process is the Canada China Business Council, which for more than three decades has actively promoted economic ties among businesses of all sizes.

The two governments could also make common cause on regional or global issues, and they share an interest in the open liberal multilateral trading system. Canada is also viewed by the Chinese as knowledgable both about the use of soft power in international relations and how to conduct a deeply integrated relationship with the United States, two of China’s main external preoccupations.

Japan

Canada’s relationship with Japan is its longest standing in the region, with formal commercial relations dating back 100 years and diplomatic ties 75 years. Despite recent environmental disasters and its aging and shrinking population, Japan’s economy will continue to be one of the world’s biggest and richest for many years to come. Japan is Canada’s third-largest trading partner and its second-largest in Asia, with two-way trade in 2010 totalling C$25 billion. Investment, however, is a different story, with two-way stocks of just C$9 billion in 2006—indeed, Japan’s stock, much of it directed at manufacturing supply chains in transportation and information technology, is growing at ever slower rates while Canada’s stock is a third of Japan’s, reflecting Japan’s reluctance to accept FDI. Trade between the two is largely complementary, with Japan buying energy and natural resources while Canada buys vehicles, machinery, electronic equipment, optical instruments, iron and steel, and pharmaceuticals.

The two countries, which share common interests in major global institutions, have developed a dense diplomatic relationship over the years which includes bilateral agreements on culture, air services, fisheries, atomic energy, science and technology, and taxation. In 2010, they agreed to study the basis for a Closer Economic Partnership Agreement. Japan’s increasing reliance on Canada to enhance its food and energy security is an important factor in launching these negotiations. There are also long- standing private sector links between Canadian businesses and Keidanren, Japan’s large-business organization. Japan is particularly interested in Canada’s Gateway project, a large infrastructure project that aims to break transportation bottlenecks at Canada’s west coast ports. The two countries are also expanding their exchange programs involving students and teachers.

South Korea

South Korea is Canada’s third largest trading partner in Asia and seventh overall, just after Germany and Mexico, In 2010, two-way trade totalled C$10 billion, two and a half times larger than Canada’s trade with India. Canada, however, is not a major trading partner of South Korea, which trades more with 20 other countries. South Korea is an important export market for Canadian agri-foods and educational services, while Canada

imports South Korean information technology products and services. Direct investment flows, however, totalled only C$1.1 billion in 2006, with South Korea investing 50 percent more in Canada than the converse.

The two countries share interests as medium-sized trading nations located beside global giants. Both recognize the importance of global economic organizations to maintain open markets and a level global playing field, and they share common positions on reforming these organizations. South Korea is very open to trade—indeed, it is the world’s twelfth-largest goods trading nation—and it is successfully exploiting its strategic location between two of the world’s largest economies, China and Japan, to become a vital supplier to their global supply chains, building on its strength in semiconductors, consumer electronics, and transportation. South Korea’s economy is now the world’s fifteenth largest as measured by real GDP, and shares thirteenth spot with Canada as measured by purchasing power parity. South Korea’s per capita income, however, is less than half Canada’s. The South Korean government has a relatively successful record of investing in new industries, which now include aerospace, biotechnology, clean technologies, robotics, financial services, and entertainment, and its “green technology” drive and its interest in natural resources and energy should present opportunities for Canadians firms.