Ambiguity and Illusion in China’s Economic Transformation: Issues for Canadian Policy Makers and Business

Executive Summary

Over the past decade, China has demonstrated that it has emerged from its long sleep. Modernization, urbanization, and marketization are taking place at a dizzying pace. With a population of more than 1.3 billion and a rapidly growing economy, China deserves full credit for its unprecedented turnaround. No other country has ever sustained double-digit growth for three decades, as did China from 1979 to 2009. If it succeeds in maintaining half that pace, it will surpass the United States at some point in the next few decades to become the world’s largest national economy.

This paper examines the impact of China’s rapid economic development on global and Canadian economic interests and considers some of the concerns raised by China’s emergence as the world’s second-largest producer and largest trader and the challenges and opportunities for Canadian policy makers and business leaders.

China’s rapid growth is remarkable not only for its depth and duration but also because it took place in the absence of many of the rules and institutions that underpin economic growth and development in most western economies. China does not score well on any of these. Corruption permeates much of the state; inequality has reached alarming proportions; wealth is concentrated in the coastal regions, while much of the interior remains much poorer and more backward; and environmental degradation has reached dangerous levels. The central government’s capacity to exercise control over this vast economy can be easily exaggerated, while the interests of local authorities may conflict with the interests of Beijing, adding to the difficulties that foreigners encounter when trying to do business in China.

Nevertheless, China’s reform program has lifted more people out of abject poverty than all of western aid combined and has improved the well-being of millions more. Yet China remains a poor country. It can now claim more than a hundred billionaires and a larger middle class than any other country, but its poor remain as numerous as the total population of North America. Such contrasts remind us not to think of China in monolithic terms. A country this large and diverse cannot be encapsulated in a few pages. China is a tremendously complex country, rife with contradictions that would take a lifetime to appreciate fully.

China’s remarkable trade performance is of particular interest to Canadians. But, like the formal governing structure, China’s trade numbers are deceptive. Much of what China exports it first imports. Thousands of foreign and Chinese firms have positioned themselves to exploit China’s comparative advantage as the final stage in sophisticated global value chains producing computers, sports equipment, clothing, household fixtures and a wide range of other products. Understanding China’s role in these global production networks is critical to understanding China’s emergence as an economic power.

The popular image of China as the manufacturing center of the world is thus misleading. Instead, China has become an integral part of a much more

complicated reality that involves leading firms in North America, Europe, and Japan, resource firms all over the world, manufacturers of components in the more advanced economies of East Asia such as Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia, and final assembly in China, Vietnam, and other countries in East

Asia.

Chinese leaders have now concluded that their success in positioning China as the point of final assembly in an integrated East and Southeast Asian manufacturing system is no longer the key to future development. They are now trying to reposition the country so that it can create a capacity for indigenous innovation, pursue scientific development, develop its own technologies and industries, and bring further inland the benefits of industrialization. If the past thirty years are anything to go by, these goals are likely to be reached sooner rather than later. Canadian firms interested in pursuing opportunities in China will do well to take these goals into account.

China’s rapid emergence as a major exporter, particularly of consumer products, has given rise to concerns about China as a fair trader, often focused on its exchange rate and large current account surpluses. Over time, however, as has happened in other countries, domestic demand will increase, particularly as the population ages and savers become spenders, albeit probably not quickly enough to satisfy US and other critics. Given Japan’s negative experience with US pressure to adjust its exchange rate in the 1980s, Chinese authorities are understandably reluctant to accede prematurely to US demands.

The oft-repeated charge that global corporations are moving capital and jobs to low-wage countries such as China at the expense of jobs and investment in North America and Europe is also simplistic and misleading. China is not replacing gross OECD output but is allowing manufacturers to continue to reap productivity gains by moving labour-intensive, less productive areas of activity offshore to China and to its suppliers of intermediate goods in the rest of Asia, and then importing finished consumer and producer goods from China, a net economic benefit to both sides.

China’s relatively weak regulatory system has given rise to serious problems resulting from the production of shoddy and even dangerous goods. For those who have short memories, however, similar concerns were expressed about shoddy Japanese, Korean, and other products. China is experiencing the same phenomenon but appears to be moving up the quality ladder more quickly than Japan, Korea, and others did during their transformations.

China’s determination to carry through with its decision to join the world trade regime is proving an important corrective to some of the excesses of rapid development. No other country has ever been scrutinized at such an exacting level of detail nor has any other acceding country been required to accept as many concessions and conditions. The accession process took fifteen years (1986-2001) and involved stipulating numerous Chinese commitments to make its trade and economic laws and practice much more transparent, uniform, predictable and market-oriented. Reviews of these commitments by the WTO’s Trade Policy Review Body every other year since 2006 indicate that China is making steady progress in meeting them.

China’s record on human rights is another area of western concern, and rightly so. Nevertheless, the quality of life of most Chinese citizens has improved immeasurably over the past thirty years. The direction of change is clear, indicating that with greater prosperity will come more pressure to loosen the bonds further.

Over the past decade, China has been Canada’s fastest-growing trading partner, albeit from a relatively small base, growing at a rate ten times faster than trade with the rest of the world. Not only has the emergence of China as a major player in global trade improved Canada’s terms of trade, it has also contributed to a marked diversification in Canadian trade patterns. Similar to Australian firms, Canadian resource companies have benefited enormously from the global surge in resource prices stimulated by rising demand in Asia. Canada is well-positioned to increase trade across the Pacific. Both South and East Asia are hungry for energy and raw materials and Canada is potentially a much more reliable and stable supplier than African, Latin American, and Middle Eastern suppliers. More will need to be done, however, to improve transportation infrastructure on the west coast and remove regulatory bottlenecks.

On balance, a prosperous China is in Canada’s – and the world’s – political and economic interests and, while it may have short-term negative effects on individual firms and workers, the long-term impact on the prosperity of Canadians should be positive. While human rights concerns and the absence of democratic rights remain serious challenges, a weakened China could well let loose nationalist and militaristic forces that would be much more destabilizing to global peace and prosperity.

As in other East Asian economies, maintaining development at its recent pace will pose a major challenge to China; so, too, will the need to address environmental, social, and other problems that are the inevitable result of rapid development. Even if growth slows to half the pace of the past thirty years, trade and investment opportunities will remain substantial for many years to come. Canada has been a relative latecomer to forging relationships in Asia, both private and public. Nevertheless, a sufficient base exists to suggest that a concerted strategy of greater engagement will pay major dividends.

Such a strategy requires active engagement by the government and the private sector. The success of government initiatives will depend on critical feedback and support from the private sector and clear evidence that Canadian firms are prepared to become more actively involved in transpacific markets. Government activity should build on the initiatives already underway, but there should be more resolve and a willingness to take on entrenched domestic protectionist forces.

Complementary efforts in Canada to strengthen the required infrastructure, to reduce regulatory bottlenecks, and to raise awareness of Canadian interests in Asia will be to ensure that efforts to enhance transpacific engagement will lead to sustained market growth. Canadians’ awareness of the importance of trade and investment and of the emergence of China and the rest of Asia is episodic and easily derailed by protectionist and other interests. Both government and business leaders need to be prepared to speak out and exercise leadership in making a robust Canadian transpacific presence a reality.

Sommaire

Au cours de la dernière décennie, la Chine a montré qu’elle a émergé de son long sommeil. La modernisation, l’urbanisation et la commercialisation ont lieu à un rythme étourdissant. Avec une population de plus de 1,3 milliard d’habitants et une économie en essor rapide, la Chine mérite tout le crédit pour son revirement sans précédent. Aucun autre pays n’a jamais soutenu une croissance à deux chiffres pendant trois décennies, comme l’a fait la Chine de 1979 à 2009. Si elle réussit à conserver la moitié de cette cadence, elle surpassera les États-Unis à un moment donné quelconque au cours des prochaines décennies pour se classer la plus importante économie nationale au monde.

Le présent document examine l’incidence du développement économique rapide de la Chine sur les intérêts économiques mondiaux et canadiens et se penche sur certaines des préoccupations soulevées par l’émergence de la Chine comme le deuxième plus important producteur et principale puissance commerciale au monde et les défis et occasions que tout cela présente pour les décideurs et les chefs d’entreprise canadiens.

La croissance rapide de la Chine est remarquable non seulement en raison de sa profondeur et de sa durée mais également en raison de sa réalisation en l’absence de nombreuses règles et institutions qui sous-tendent la croissance et le développement économiques de la plupart des économies occidentales. La Chine n’a pas obtenu un très bon rendement sur l’un ou l’autre de ces fronts. La corruption imprègne une bonne partie de l’État; les inégalités atteignent des proportions inquiétantes; la richesse est concentrée dans les régions côtières, tandis qu’une large zone intérieure demeure beaucoup plus pauvre et plus arriérée; et la dégradation de l’environnement a atteint des niveaux dangereux. La capacité du gouvernement central d’exercer une mainmise sur cette vaste économie peut être facilement exagérée, tandis que les intérêts des autorités locales peuvent entrer en contradiction avec ceux de Beijing, ce qui ajoute aux difficultés qu’éprouvent les étrangers au moment de tenter de faire affaire en Chine.

Néanmoins, le programme de réforme de la Chine a propulsé plus de gens hors des confins de la misère affreuse que toute l’aide occidentale combinée et a amélioré le mieux-être de millions de personnes de plus. Pourtant la Chine demeure un pays pauvre. Elle peut désormais se targuer de compter plus d’une centaine de milliardaires et une classe moyenne plus imposante que tout autre pays, mais ses pauvres demeurent aussi nombreux que la population totale de l’Amérique du Nord. Pareils contrastes nous rappellent de ne pas penser à la Chine en termes monolithiques. On ne peut résumer en quelques pages un pays aussi vaste et diversifié. La Chine est un pays incroyablement complexe, et abondant en contractions auxquelles il faudrait consacrer toute une vie pour pleinement les recenser.

Le rendement commercial remarquable de la Chine revêt un intérêt particulier pour les Canadiens. Mais, tout comme la structure officielle qui la gouverne, la Chine affiche des données décevantes sur le plan de ses échanges. Une bonne part de ce que la Chine exporte, elle l’importe d’abord. Des milliers d’entreprises étrangères et chinoises se sont positionnées de manière à exploiter l’avantage comparatif de la Chine comme l’ultime étape de chaînes de valeur mondiales évoluées produisant des ordinateurs, de l’équipement de sport, des vêtements, des accessoires ménagers et toute une gamme d’autres produits. Comprendre le rôle de la Chine dans ces réseaux de production planétaires est d’une importance cruciale pour comprendre l’émergence de la Chine à titre de puissance économique.

L’image populaire de la Chine comme centre manufacturier du monde est donc trompeur. En lieu et place, la Chine est devenue partie intégrante d’une réalité beaucoup plus complexe qui regroupe les entreprises dominantes d’Amérique du Nord, d’Europe et du Japon, les entreprises de ressources à l’échelle mondiale, les fabricants de composants des économies les plus avancées d’Asie orientale telles que la Corée, Taïwan et la Malaisie, et l’assemblage final en Chine, au Vietnam et dans d’autres pays de l’Asie orientale.

Les dirigeants chinois ont maintenant conclu que leur démarche réussie pour positionner la Chine comme point d’assemblage final dans un système de fabrication est-asiatique et sud-asiatique intégré n’est plus la clé de son développement à venir. Ils tentent désormais de repositionner le pays pour qu’il puisse créer une capacité d’innovation locale, viser le développement scientifique, mettre au point ses propres technologies et industries, et d’apporter les avantages de l’industrialisation toujours plus loin à l’intérieur du pays. Si on doit se fier à ce qui s’est produit au cours des trente dernières années, on atteindra vraisemblablement ces objectifs plus tôt au lieu de plus tard. Les entreprises canadiennes qui souhaitent chercher à débloquer des débouchés en Chine auront avantage à tenir compte de ces objectifs.

L’émergence rapide de la Chine comme grand exportateur, surtout des produits de consommation, a soulevé des préoccupations à propos de la Chine à titre de d’exportateur loyal, souvent axé sur son taux de change et ses imposants excédents sur les comptes actuels. Au fil du temps, toutefois, comme cela s’est produit dans d’autres pays, la demande intérieure augmentera, particulièrement au gré du vieillissement de la population et de la transformation des épargnants en dépensiers, quoique probablement pas assez rapidement pour combler les critiques des États-Unis et des autres pays. Compte tenu de l’expérience négative du Japon avec la pression américaine de rajuster son taux de change durant les années 1980, les autorités chinoises sont, et c’est compréhensible, hésitants à se plier prématurément aux exigences des États-Unis.

L’accusation maintes fois répétée que les sociétés internationales déplacent les capitaux et les emplois vers des pays à faibles salaires tels que la Chine au détriment des emplois et des investissements en Amérique du Nord et en Europe est également simpliste et trompeuse. La Chine ne remplace pas l’extrant brut de l’OCDE mais permet aux fabricants de continuer de écolter les fruits de la productivité en déménageant les secteurs d’activité denses en main-d’œuvre et moins productifs vers des lieux extraterritoriaux en Chine, et les fournisseurs de biens intermédiaires vers le reste de l’Asie, puis en important des produits de consommation et de production finis de la Chine, un avantage économique net pour les deux parties.

Le système réglementaire relativement faible de la Chine a engendré des problèmes graves découlant de la production de produits mal faits, voire dangereux. Pour ceux qui ont la mémoire courte, cependant, on a exprimé des préoccupations semblables à propos des produits japonais, coréens et autres de mauvaise qualité. La Chine est confrontée au même phénomène mais elle semble gravir l’échelle de la qualité plus rapidement que le Japon, la Corée et les autres l’ont fait durant leur transformation.

La détermination de la Chine à aller jusqu’au bout de sa décision de joindre le régime commercial mondial s’avère un important correctif apporté à certains des excès en matière de développement rapide. Aucun autre pays n’a jamais été scruté selon un niveau de détail aussi pointu et aucun autre pays en lice n’a été tenu d’accepter autant de dérogations et de conditions. Le processus d’accession s’est échelonné sur quinze ans (1986-2001) et il a comporté l’épreuve d’énoncer les nombreux engagements de la Chine à rendre ses lois et pratiques commerciales et économiques beaucoup plus transparentes, uniformes, prévisibles et axées sur le marché. Un examen de ces engagements par l’organe d’examen des politiques commerciales de l’OMC tous les deux ans depuis 2006 révèle que la Chine marque des pas constants vers le respect de ces engagements.

Le bilan de la Chine en matière des droits de la personne est un autre aspect qui inquiète le monde occidental, et c’est à juste titre. Néanmoins, la qualité de vie de la plupart des citoyens chinois s’est améliorée incommensurablement au cours des trente dernières années. Le changement a emprunté une direction nette, indiquant que la prospérité accrue s’accompagne de plus de pression pour resserrer davantage l’étau.

Au cours de la dernière décennie, la Chine a été le partenaire commercial du Canada qui a connu le plus d’essor, quoique partant d’une base relativement réduite, elle a augmenté à un rythme dix fois plus rapide que le commerce avec le reste du monde. Non seulement l’émergence de la Chine en tant qu’acteur important de l’échiquier du commerce international a-t-elle amélioré les conditions commerciales du Canada, mais elle a également contribué à une diversification marquée des habitudes commerciales canadiennes. Tout comme les entreprises australiennes, les sociétés de ressources canadiennes ont bénéficié énormément de la crête mondiale des prix des ressources stimulée par une demande croissante enregistrée en Asie. Le Canada est bien positionné pour augmenter les échanges à l’échelle du Pacifique. L’Asie méridionale et l’Asie orientale sont assoiffées d’énergies et de matériaux bruts, et le Canada est potentiellement un fournisseur beaucoup plus fiable et stable que les fournisseurs africains, latino- américains et moyen-orientaux. Il reste encore beaucoup de chemin à parcourir, cependant, pour améliorer l’infrastructure des transports sur la côte ouest et éliminer les goulots d’étranglement sur le plan de la

réglementation.

Tout compte fait, une Chine prospère y va des intérêts politiques et économiques du Canada – et du monde – et, bien qu’elle puisse avoir des effets négatifs à court terme sur les entreprises individuelles et les travailleurs, l’incidence à long terme sur la prospérité des Canadiens devrait être positive. Tandis que les préoccupations par rapport aux droits de la personne et l’absence de droits démocratiques demeurent des défis graves, une Chine affaiblie pourrait bien libérer les forces nationalistes et militaristiques qui seraient beaucoup plus déstabilisantes pour la paix et la

prospérité mondiales.

Comme dans les autres économies est-asiatiques, conserver le développement à son rythme récent posera un défi de taille pour la Chine; il en va de même du besoin de résoudre les problèmes environnementaux, sociaux et autres qui sont le produit inévitable d’un développement rapide. Même si la croissance ralentissait à la moitié de la cadence enregistrée au cours des trente dernières années, les possibilités de commerce et d’investissement resteront considérables pendant de nombreuses années à venir. Le Canada est plutôt un retardataire dans l’établissement de liens avec l’Asie, sur les plans à la fois privé et public. Néanmoins, une base suffisante existe pour nous permettre d’avancer qu’une stratégie concertée de mobilisation accrue donnera des dividendes importants.

Pareille stratégie exige un engagement actif du gouvernement et du secteur privé. La réussite des mesures gouvernementales dépendra d’une rétroaction et d’un soutien cruciaux de la part du secteur privé et d’une preuve nette que les entreprises canadiennes sont prêtes à devenir plus actives sur les marchés transpacifiques. L’activité gouvernementale devrait se fonder sur les initiatives déjà amorcées, mais il devrait y avoir plus de détermination et une volonté à prendre d’assaut les forces protectionnistes intérieures intransigeantes.

Les efforts complémentaires du Canada pour renforcer l’infrastructure requise, pour réduire les goulots d’étranglement réglementaires et pour augmenter la conscience des intérêts canadiens en Asie chercheront à s’assurer que les efforts pour améliorer l’engagement transpacifique mènent à une croissance commerciale soutenue. La sensibilisation des Canadiens à l’importance du commerce et de l’investissement et à l’émergence de la Chine et du reste de l’Asie est épisodique et facilement déraillée par les intérêts protectionnistes et autres. Le gouvernement et les chefs d’entreprise, ont tous deux besoin d’être prêts à s’exprimer et à faire preuve de leadership pour faire d’une robuste présence transpacifique canadienne une réalité.

Introduction

What a difference 35 years can make. In 1974, China sent a delegation led by Deng Xiaoping to the United Nations in New York and had difficulty scraping together the $38,000 in foreign exchange needed for the airfare and hotel expenses. By 2009, China held some $2 trillion dollars in foreign exchange. In 1976, the idea that China could bail out over-extended European governments would have been considered preposterous, if not insulting. In 2011, not only did European governments approach Chinese officials for help in rescuing the Euro, but Chinese officials turned them down, considering good relations with Europe less important than sound

investments. China has come a long way over the past 35 years, and the world is a different place as a result.

With a population of more than 1.3 billion and a rapidly growing economy, China deserves full credit for its unprecedented turnaround. No other country has ever sustained double-digit growth for three decades, as did China from 1979 to 2009. If it succeeds in maintaining half that pace, it will surpass the United States at some point in the next few decades to become the world’s largest national economy. It is already the world’s leading exporter and trails only the United States as an importer. It is now twice as dependent on international trade as the comparably sized US, Japanese and EU economies. From a humanitarian perspective, this is a welcome development. China’s reform program has lifted more people out of abject poverty than all of western aid combined and has improved the well-being of millions more. As one newly empowered resident of Shanghai put it, “Once you are accustomed to using a private bathroom rather than a shared neighbourhood public toilet, it is hard to go back to squatting next to your neighbours.” (Gerth 15).

Yet China remains a poor country. It can now claim more than a hundred billionaires and a larger middle class than any other country, but its poor remain as numerous as the total population of North America. In 30 years, China has gone from being the country with the least economic disparity to being one of the most unequal. Its Gini coefficient, a common measure of income inequality, is 0.42, similar to that of the United States.

Such contrasts remind us not to think of China in monolithic terms. A country this large and diverse cannot be encapsulated in a few pages. China is a tremendously complex country, rife with contradictions that would take a lifetime to appreciate fully. As its economy has expanded and become more sophisticated, it has begun to experience the macro- and micro-economic challenges that any large economy faces and which its political leaders are under pressure to address: corruption, business failures, abuse of dominant positions, and shoddy goods competing with quality goods, to name only a few. The central government’s capacity to exercise control over this vast economy can be easily exaggerated, while the interests of local authorities may conflict with the interests of Beijing, adding to the difficulties that foreigners encounter when trying to do business in China.

The rapid development that has taken place over the last thirty years was originally concentrated in the coastal regions, particularly in the cities and provinces closest to Hong Kong and Shanghai. Similar developments are now taking place further inland, but the challenges remain huge. More than half the people still lives in rural areas still largely untouched by modernization. China may boast the world’s largest manufacturing workforce at over a hundred million workers, but it is also saddled with a pool of up to seventy million under-employed workers living on the periphery of urban centres, and more to come from farms and villages as the wealth of cities pulls them in. Rural output now contributes 11 percent to GDP while accounting for 40 percent of the workforce. Domestic demand, while growing, remains underdeveloped and the high savings rate, a plus in the early stages of China’s development, is now a drag on the economy. Environmental degradation and social tensions from rapid development have reached alarming proportions.

China’s rapid growth is remarkable not only for its depth and duration but also because it took place in the absence of many of the rules and institutions that underpin economic growth and development in most western economies. In Ken Lieberthal’s words, western public policy maintains that “the best path to optimum growth combines high-quality governing institutions, a relatively free market, the rule of law, liberal democracy, open capital and commodities markets, and good corporate governance.” (Lieberthal xiii) China does not score well on any of these. Its leaders can point to national laws and institutions that superficially appear similar to those in Canada and other market economies, but in reality such provisions are largely immaterial to the way China’s economy functions. Instead, provincial and municipal officials exercise a high degree of discretion in attracting investment, providing permissions, and applying many other regulatory requirements, subject only to broad supervision by national authorities and communist party officials. The nature of this supervision remains ambiguous, resulting in creative tensions between local and national officials, and high levels of what Breznitz and Murphree call “structured uncertainty.” The fine line between nimble decision-making and corruption is not always clear. This institutionalized ambiguity poses major challenges to Canadian policy makers and business leaders who seek closer relations with China.

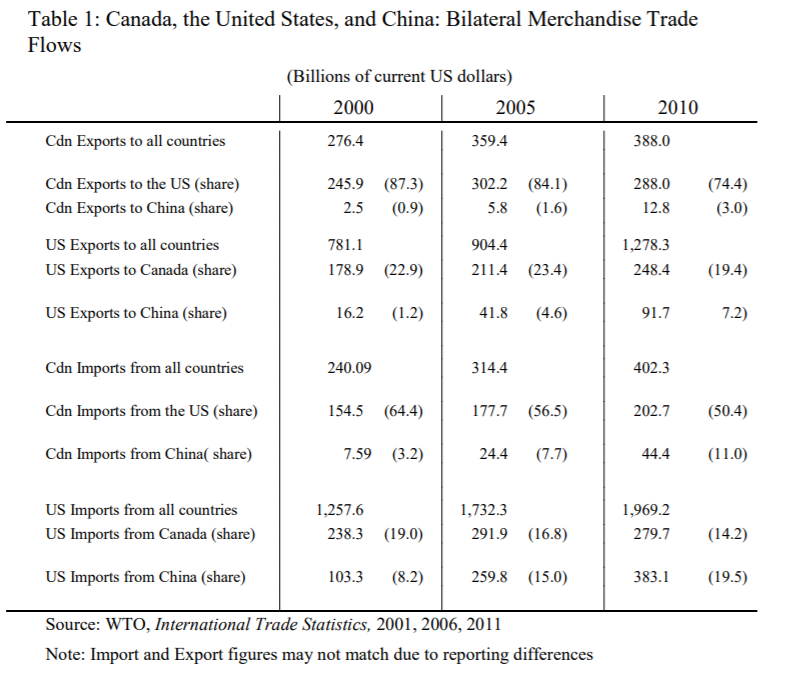

China’s remarkable trade performance is of particular interest to Canadians. Canada-US trade, the bread and butter of the Canadian economy through most of the post-war era, has stagnated since it reached a peak in 2000. Slow growth in the US economy, the post 9/11 thickening of the bilateral border, the reluctance of the US government to address post-NAFTA bilateral trade issues, and the emergence of Asia as a major economic force have combined to reduce the role of the US market in the Canadian economy. China held 19.5 percent of the US merchandise import market in 2010, while Canada’s share had shrunk to 14.2 percent. In the other direction, China was the source of 11 percent of Canada’s imports in 2010 while the US share had declined to 50.4 percent (see Table 1). Some see China as an important contributor to the bilateral trade malaise, taking an increasing share of Canadian exports and a growing share of both import markets. On the basis of conventional trade statistics, China has overtaken Canada as the leading supplier to the US market and is now the second largest supplier to the Canadian market.

But like the formal governing structure, China’s trade numbers are deceptive. Much of what China exports it first imports. Thousands of foreign and Chinese firms have positioned themselves to exploit China’s

comparative advantage as the final stage in sophisticated global value chains producing computers, sports equipment, clothing, household fixtures and a wide range of other products. Understanding China’s role in these global production networks is critical to understanding China’s emergence as an economic power.

Not everyone views China’s remarkable economic transformation in a positive light. Recent literature on China has seen its share of sinophobes, from mild complaints by commentators such as the Petersen Institute’s Fred Bergsten (who sees currency manipulation behind every successful Asian competitor to the United States) to more populist authors such as Peter Navarro and Greg Autry (Death by China: Confronting the Dragon – A Global

Call to Action) and Stephen Leeb (Red Alert: How China’s Growing Prosperity

Threatens the American Way of Life). Many of these critics focus on the dark side of China’s institutional ambiguity: the corruption, uncertainty, and other social ills that are an unfortunate dimension of China’s rapid development.

More useful are recent books and articles by scholars seeking to explain China’s rapid ascent up the economic ladder, its newfound geopolitical prowess, the transformation in China’s governing structures, the relative social and economic harmony that characterizes modern China, and the daunting social and environmental issues that Chinese authorities must address if the country is to sustain the gains it has made. These include interesting and provocative works by Chinese scholars, suggesting much more lively internal debate and discussion than one would expect in a totalitarian society. They add to the enigma that is modern China.

On balance, a prosperous China is in Canada’s – and the world’s – political and economic interests and, while it may have short-term negative effects on individual firms and workers, the long-term impact on the prosperity of Canadians should be positive. While human rights concerns and the absence of democratic rights remain serious challenges, a weakened China could well let loose nationalist and militaristic forces that would be much more destabilizing to global peace and prosperity.

This paper examines the impact of China’s rapid economic development on global and Canadian economic interests. It takes a longer term perspective. Major changes such as the emergence of China as a global economic player are bound to upset established patterns and require adjustment. The paper takes as a given that short-term adjustment pressures will roil the political landscape but concludes that they will have little impact on the underlying, positive structural changes taking place. The paper begins with a brief overview of China’s recent economic development and political transformation before turning to a discussion of the changing structure of global trade and production and China’s role within this structure. Against that background, it considers some of the concerns raised by China’s emergence as the world’s second-largest producer and largest trader and the challenges and opportunities for Canadian policy makers and business leaders.

A Sleeping Giant Awakens

The story of China’s rapid economic rise starts with the historic reversal of its centuries-long preference for isolation. For much of its history, China boasted the world’s most advanced civilization and most productive economy. At the dawn of the modern era, however, China turned inward. European and US efforts to open China to western influence and trade made some headway in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but proved damaging to Chinese internal cohesion and self-confidence. This “century of humiliation” culminated in the Japanese invasion and occupation of China in the 1930s and 1940s. It took the communist revolution of 1949 to re-forge a united China and to restore national self-respect. The revolutionary government’s instinct, once it had consolidated power over the country, was to continue and even strengthen China’s isolation, except for ties to the communist world.

The first decade after the revolution saw the emergence of China as a Soviet satellite, dependent on Soviet technology and economic planning. By the end of that decade, however, Mao had second thoughts about ties with the Soviet Union and its allies and determined to rely on Chinese ingenuity and ideas alone. Russian advisors were sent home as China embarked on the disasters of the Great Leap Forward (1958) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). Only following the death of the revolution’s leaders – particularly Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai – did a new generation of more pragmatic leaders begin cautiously to open the door to Chinese engagement with the world.

Deng Xiaoping, who had survived and learned from the disasters of the few decades of communist rule, guardedly began the reform process by allowing inward investment by overseas Chinese, bringing in scarce capital and expertise, then inviting broader participation, and finally harnessing high levels of domestic savings. China’s development may have been export-led, but these exports were made possible by the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI); by the turn of the 21st century China had become the world’s leading destination for new FDI. The buildup of foreign capital and domestic savings – estimated to be as high as fifty percent of GDP – fuelled a rapid expansion of export-oriented manufacturing capacity and, more importantly, the modernization of infrastructure. Meanwhile, Deng allowed China’s farmers and nascent entrepreneurs more room to develop markets and keep their profits. His reforms led to what he called socialism with Chinese characteristics. More accurately, it became capitalism with socialist characteristics, and it ignited an economic boom. China’s take-off growth levels are now in their fourth decade, a performance level unmatched in earlier decades by Japan and the East Asian Tigers, and undeterred by setbacks such as the political fallout from the brutal crushing of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the global financial crisis in 2008.

Under Deng’s leadership, China crossed an historic and psychological divide in its willingness to engage with the world. At best, China’s geopolitical focus in the past had been regional, but Deng recognized that China’s economic future and security demanded a new, more open approach. Deng also had the foresight to reform the internal workings of the state, giving local officials the room to invite foreign and local entrepreneurs to pursue business opportunities in their provinces and cities.

Mao had sought to convert Chinese culture into a revolutionary, transformative force. He managed to unite the country after a century of chaos and weakness – but he did not succeed in transforming it. Deng, on the other hand, harnessed Chinese virtues and culture and, in so doing, brought the country into the 21st century as a much more powerful force than anything Mao had been able to achieve. As Henry Kissinger explains: “Mao destroyed traditional China and left its rubble as building blocks for ultimate modernization. Deng had the courage to base modernization on the initiative and resilience of the individual Chinese. The China of today … is a testimonial to Deng’s vision, tenacity, and common sense.” (Kissinger 2011: 321) Deng’s successors as supreme leader, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, were groomed by him and continued in the mould of pragmatism rather than revolutionary orthodoxy.

Chinese state bureaucracy had for over a thousand years advanced on the basis of competitive examinations, with the central government relying on scholar rulers under the benign supervision of the Emperor. Dynasties came and went, but officials were forever. The secret to political harmony and continuity in governance was well-established in China long before it became a mainstay of western democracies. From China’s perspective, this continuity was interrupted by a century of humiliation at the hands of western barbarians. The communist revolution brought an end to this humiliation and knitted the country back together, re-imposing the authority of a central government in Beijing, and re-establishing stable local governance, but at a high cost. Deng allowed the iron fist of the revolutionary, totalitarian central government to give way gradually to more traditional governance by professional bureaucrats advancing on the basis of competence. China remains a totalitarian state, but one with traditional Chinese characteristics. (Perkins 2010)

Those Chinese characteristics involve a high degree of ambiguity and opacity. Rather than exercising control over all aspects of the economy from the centre, Deng’s reforms downloaded much of this control to provincial and municipal authorities acting on the basis of broad goals and policies set in Beijing, and with non-transparent, dual supervision by the relevant ministries and the communist party. In Breznitz and Murphree’s words, “In China, at the same time that a plurality of policy actions is tolerated, the punishment of those deemed transgressors can be severe, abrupt, and arbitrary. The limits of tolerance are undefined, which adds another layer of ambiguity. Furthermore, the multiplicity of actions and procedures themselves create more uncertainty, since no one is sure what the proper course of action is or where lines of authority and responsibility reside.” (Breznitz and Murphree 2011:38) In these circumstances personal relationships, rather than rules and regulations, are paramount. Laws may be on the books, but their interpretation and implementation often hinge on whether one has carefully cultivated the right officials.

The results have been impressive, but at a cost. The Chinese economy grew at an average rate of 10 percent per annum for more than thirty years, enough to generate a sixteen-fold increase in output. Trade and foreign investment grew even faster. In 2010 China became the world’s second largest trader, its exports ranking first and its imports second after the United States. China has scoured the world for the raw materials it needs to feed its modernization, becoming an important foreign investor in its own right, while global corporations have increased the flow of components for the growing range of products assembled in Chinese factories. On the export side, China’s role as the world’s leading low-cost economy has attracted overseas investment in facilities that finish a dizzying array of consumer and producer goods. The cost of all this progress, however, has been high. Corruption permeates much of the state; inequality has reached alarming proportions; wealth is concentrated in the coastal regions, while much of the interior remains much poorer and more backward; and environmental degradation has reached dangerous levels.

The Changing Structure of Global Trade and Production

China’s remarkable growth is in part the result of deliberate policy choices by Deng and his successors, but it has also benefited from the re- organization of global production. At the same time that China was opening its market and inviting in foreign firms and investors, global industry was re- tooling to take advantage of a number of interrelated phenomena: the steady decrease in the cost of international communications and transportation, the first realization of the logistical possibilities opened up by increasingly sophisticated but low-cost computing power, and a significant reduction in government-imposed barriers to international exchange. The resultant globalization was not only a matter of growing international trade and investment, but even more of a re-organization of production along global lines and a concomitant increase in trade in parts and services and in international investment. China’s ability to offer a large, low-cost but relatively educated work force and its willingness to create conditions in which to harness this labour force proved an irresistible magnet for international investors.

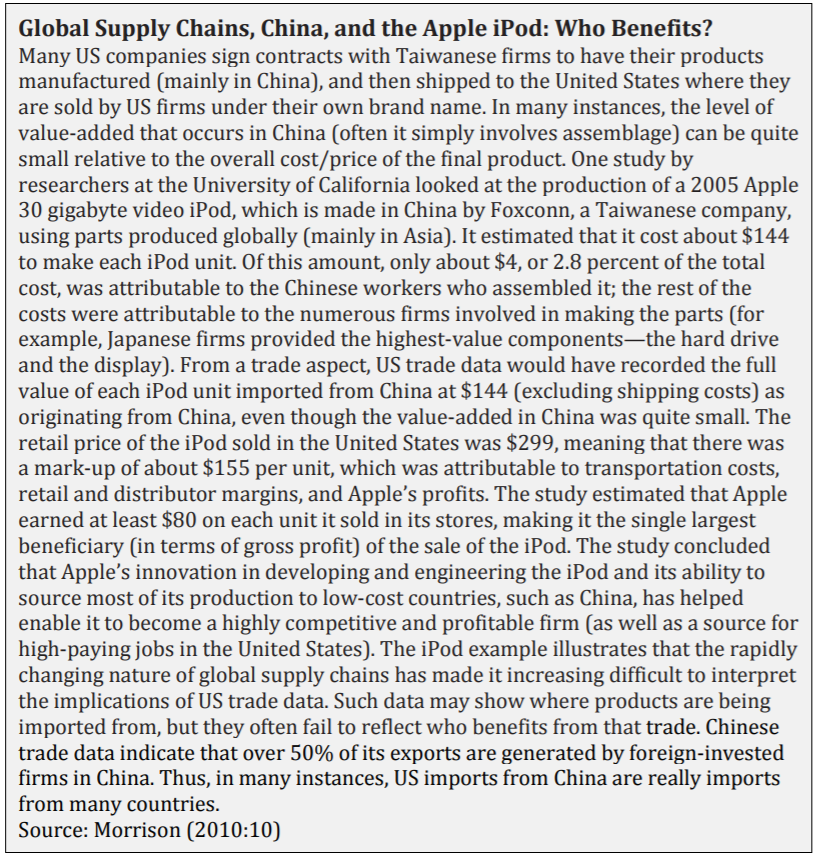

National trade statistics continue to record flows of trade and investment as though they were the outcome of arm’s-length transactions between nationally organized firms. The reality, however, is that intermediate products moving across borders in value chains – and investments within multinational firms and networks to foster the growth of value chains – have become the principal drivers of international exchange. National statistical agencies are struggling to find a satisfactory way to measure the extent and impact of this new paradigm; current statistics fail to capture the contributions of the myriad actors participating in this complex, multi- country production process. For example, national trade statistics count an Apple computer as a Chinese export because it was assembled in, and shipped from, China. In reality, it is the fruit of the design, engineering, and marketing input of the brains at Apple’s Cupertino, California, campus, incorporating many inputs from suppliers in other parts of Asia, before being assembled in China (see box below).

Contract manufacturers play an increasingly critical part in the success of value chains. Li & Fung of Hong Kong is a prime example of a modern specialist managing the logistics of fragmentation and agglomeration. It has access to a network of some 7,500 contract suppliers employing as many as 1.5 million workers in China and Southeast Asia. It provides a critical mediating service bringing brand-name firms together with highly efficient contract manufacturers. Li & Fung takes orders from brand-name companies all over the world to “make things” for them, from intermediate parts and components, to furniture, golf clubs, computers, and televisions. It in turn finds the appropriate contract manufacturer and organizes the logistics to supply the ordered “thing” to the customer, based on the customer’s specifications. Many contract suppliers maintain offices in Hong Kong to liaise with Li & Fung and similar firms to provide them with product development and engineering information.

Baldwin and Gu cogently summarize the economic benefits that flow from this new international division of labour: “Offshoring is related to productivity growth, shifts to higher value-added activities and changes in labour markets. Outsourcing of products to sources outside of Canada can potentially affect the type of production that is done in Canada and also affect labour markets. Offshoring production potentially moves producers up (or down) the value chain and may affect productivity if it allows for the substitution of inefficient internally produced goods with less expensive and superior inputs from abroad” (Baldwin and Gu 2008:41).

Offshoring and related new production patterns, while raising productivity and efficiency and driving down prices, thus boosting prosperity, do have short-term negative distributional effects. Firms and workers in Canada and other advanced economies who are displaced by this process of creative destruction will feel the negative effects most acutely. This is an age-old phenomenon and explains the political economy of trade policy: the politics of trade rest on the reality that there are votes in promoting exports but not, generally speaking, in facilitating imports. The economic benefits of trade, on the other hand, flow from expanding the market, facilitating specialization and the international division of labour, exploiting comparative advantage among producers, increasing productivity, and providing consumers with access to the best the world has to offer at competitive prices.

The postwar multilateral process of mercantilist bargaining gave governments in the developed countries the necessary political cover to negotiate agreements that delivered on the economic promise. The expansion of this process to China and other emerging economies is wholly consistent with both the success and the politics of earlier experience. The political rhetoric of trade may well continue to harp on distributional costs, perhaps slowing down realization of the full economic benefits that can be derived from new patterns of globalized production, but it is unlikely to alter the direction of change.

China’s Role in the New Global Economic Structure

No other country has embraced the benefits of these new trade and production patterns more enthusiastically than China. The process of increasing value through disaggregation and re-bundling is critical to understanding the rapid growth in China’s trade. It provided the means by which the political and economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s could be harnessed to bring development to large parts of China and its huge population of underemployed workers. China has thus emerged as the prime site for locating labour-intensive assembly and related activities, replacing other Asian suppliers that have moved up the value chain to supply components used by assembly facilities in China. More than three-quarters of the value of Chinese exports represent imported components, and more than two thirds of Chinese imports are for use in exports.

The popular image of China as the manufacturing center of the world is thus misleading. Instead, China has become an integral part of a much more complicated reality that involves leading firms in North America, Europe, and Japan, resource firms all over the world, manufacturers of components in the more advanced economies of East Asia such as Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia, and final assembly in China, Vietnam, and other countries in East Asia. The fact that many of the end products of these intricate global production chains are shipped from China gives the false impression that Chinese firms are the principal providers of this cornucopia of products, rather than relatively minor contributors. In the absence of more sophisticated trade statistics that can trace the value-added at each stage of production, people will continue to draw false conclusions and governments will be tempted to pursue wrong-headed policy prescriptions.

Three principal economic actors have played roles in China’s economic development. At the outset, China relied on its thousands of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in competition with one another for foreign markets, capital and partners. As the reforms took hold, however, their role steadily declined, except in the resource sector, heavy industry, traditional low-end manufacturing (from toys to clothing), banking, and in the provision of infrastructure. Many of the SOEs in these sectors are larger than the largest Canadian firms and have become significant players in the global economy. The Fortune Global 500 list for 2011 includes 61 Chinese firms – double the number of British, German and French firms – many of which are SOEs. The success of these companies suggests that Chinese firms – private and public – understand very well how capitalism works. The relative decline in SOEs in other sectors provided more and more room for foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs), initially from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and Korea and increasingly from Australia, North America, and Europe, either directly or through Hong Kong or Taiwanese intermediaries. Most of these FIEs are focused on consumer products for export, integrating Chinese assembly into internationally organized value chains, but some are also beginning to focus on the Chinese market. Finally, Chinese entrepreneurs are emerging as suppliers of goods and services to SOEs and FIEs and, more recently, as providers in their own right of non-traditional, technology-intensive products for both export and domestic markets.

As noted, Chinese central authorities initially sought to orchestrate this economic renaissance from the centre but soon accepted that the state possessed neither the institutional nor human capacity for such a massive undertaking. Instead, reformers in Beijing increasingly provided local officials at the provincial and municipal level with the authority to grant permissions and to work with both domestic and foreign investors. Competition among provincial and municipal authorities proved both a boon and a problem. By releasing competitive forces around the country, initially in the coastal regions but then more generally, more could be accomplished than by centralizing decision-making in Beijing. At the same time, these competitive forces have exacerbated the environmental, social, and other regulatory problems now facing the state, while blurring the distinction between private enterprise and the state.

Crony capitalism can be a major problem for foreign entrepreneurs, as can inconsistent, opaque, and unreliable application of rules and policies. As Keneth Lieberthal notes, “[I]n China the state is always at least your silent partner. The best business plans will fail if relevant officials turn against them, and state officials can profoundly affect the business opportunities available to any firm.” (Lieberthal 2011: xv) The Chinese banking system remains underdeveloped despite the willingness of the authorities to allow foreign participation in the banking sector. As in Japan, local entrepreneurs enjoy access to the vast resources of domestic savings at favourable rates denied to FIEs. Non-performing loans are a major drag on the banking system.

Chinese leaders have now concluded that their success in positioning China as the point of final assembly in an integrated East and Southeast Asian manufacturing system is no longer the key to future development. Lieberthal notes that “this overall strategy has kept the country at the low end of the international value chain, where it has achieved preeminence in metal bending but not in higher value-added R&D, product design and development, sales, service, branding, and finance, which are key to prosperity on a nation-wide basis.” (Lieberthal 2011: 8-9) China’s leaders are now trying to reposition the country so that it can create a capacity for indigenous innovation, pursue scientific development, develop its own technologies and industries, and bring further inland the benefits of industrialization. If the past thirty years are anything to go by, these goals are likely to be reached sooner rather than later. Canadian firms interested in pursuing opportunities in China will do well to take these goals into account.

China’s determination to carry through with its decision to join the world trade regime is proving an important corrective to some of the excesses of rapid development. The United States, the EU and others, particularly China’s neighbours in East Asia, insisted that China’s membership would depend on its full acceptance of the multilateral trade rules. China’s assertion that it was a developing country and entitled to some slack fell on deaf ears. China’s potential market size, low wages, large population, and non-market economy drew wide, searching interest from members. No other country has ever been scrutinized at such an exacting level of detail nor has any other acceding country been required to accept as many concessions and conditions. The slow pace was in part a product of China’s reluctance to make the required changes in domestic laws and practice and in external protection, but once it became clear that the long-term economic benefits of acceding outweighed the short-term political costs of concessions, China did what it had to do.

The accession process took fifteen years (1986-2001) and involved stipulating numerous Chinese commitments to make its trade and economic laws and practice much more transparent, uniform, predictable and market-oriented. Reviews of these commitments by the WTO’s Trade Policy Review Body every other year since 2006 indicate that China is making progress in meeting them. Its level of external protection is now comparable to that of the United States and Europe Communities at the end of the Kennedy Round (1964-67) and that of Japan and Canada at the end of the Tokyo Round (1973-79). The pace and direction of change to date are remarkable for a country at this stage in its economic development but, given the inherent lack of transparency and ambiguity in China’s governance, there remains considerable room for improvement. China’s approach to intellectual property provides a case in point. Karl Gerth points out that “weak protections and a massive manufacturing capacity create an unusually unstable brand environment” (Gerth, 133). Bown and McCulloch add:

Given China’s much lower per capita income, only a small fraction of Chinese consumers can yet afford the products that represent US comparative advantage, i.e., those supplied by intellectual-property-intensive industries (e.g., films, music, software, pharmaceuticals), when sold at prices that reflect full enforcement of US intellectual property rights. Moreover, Chinese consumers’ desire to acquire those goods at affordable prices feeds the demand for pirated and copycat goods produced locally, thereby adding to US complaints regarding China’s lax enforcement of intellectual property rights. But this consumption pattern also implies that China’s continued growth may help to increase still further the country’s already large imports from the United States.” (Bown and McCullogh 2009:671-2)

Some firms have learned to accept this reality, while others insist that nothing short of full compliance will do. Time and economic development may bring this issue into a more satisfactory balance, but it will require that the laws and regulations that are now on the books be interpreted and implemented at the local level in a much more transparent, predictable, and uniform level.

Following its accession in 2001, China enjoyed a five-year grace period from WTO dispute settlement complaints. Once the grace period ended, the US, the EU, Canada, and others initiated complaints about specific Chinese practices under the terms of the WTO’s dispute settlement provisions. China has also exercised its right to question US practices and those of others. Similar to Canada-US, US-EU, and US-Japan trade frictions, such disputes are the inevitable products of vigorous competition and a functioning multilateral trading system. They also provide opportunities for western governments to effect changes in the way China interprets and applies the rules and thus reduce the lack of transparency and ambiguity that now characterizes the Chinese regulatory regime.

China has assumed a growing role in the operation of the multilateral trading system without the kinds of problems that some feared in the years leading to its accession. China has been content to learn and find its place. As it has become more confident, China has obviously demanded a voice and influence commensurate with its role as one of the world’s leading traders. The frequency and constructive tone of its trade policy reviews point to acceptance of a role that will expand over time. Its reluctance to play more of a leading role in the current Doha Round of trade negotiations has been seen by some as failure to accept its full responsibilities as a leading trader. Perhaps, but the problems of the Doha Round go well beyond China; there are more than enough candidates to blame for the lack of progress. The need for some accommodation to new geopolitical and economic realities as well as new players also goes well beyond China.

Canadians have contributed to the emergence of China. As consumers, they have been contributors to the demand for low-cost finished goods, from clothing and footwear to electronics and machinery. As traders and investors, they have begun to turn to China as the location of choice for labour-intensive operations in increasingly sophisticated global value chains, as well as a potential market for Canadian goods. Canadian manufacturers have been relatively minor participants in this process, often as junior partners in US-anchored value chains. Canadian resource firms, on the other hand, are growing suppliers of raw materials for the Chinese economy and major beneficiaries of the Chinese-fuelled global commodity boom. Canadian firms, for example, are major suppliers of organic chemicals such as ethylene glycol, a key ingredient in man-made fibres for the clothing industry, as well as coal, wheat, canola oil, wood pulp for paper-making, and other commodities. Even in areas for which Canada is not a major supplier, Chinese demand has driven up world prices, strengthening the position of Canada’s resource sector. Finally, Canadian service firms are beginning to penetrate the Chinese economy. Manulife Financial, for example, is active in fifty provinces and municipalities and is now China’s largest foreign supplier of insurance and other financial instruments.

Against this background, we now turn to some of the points of contention commonly heard in Canada about China’s emergence as an economic power and consider whether they are more matters of perception than reality.

Concerns and Misconceptions

China’s rapid emergence as a major exporter, particularly of consumer products, has given rise to concerns about China as a fair trader, often focused on its exchange rate and large current account surpluses. China’s trade surplus with the United States is particularly striking. As noted above, however, the conventional trade statistics which give rise to these concerns are seriously misleading. China may have become the world’s leading exporter, but it is also the world’s second largest importer, not only of raw materials, machinery, and other goods for its own consumption, but also of components for incorporation into the finished products it exports. In terms of value added, Chinese trade figures are much more in balance.

Nevertheless, growth in exports to China trails global imports from China by a significant margin. China is now the world’s largest creditor nation, maintains a large current account surplus, particularly with the United States, and held $3.2 trillion in reserves by mid-2011, mostly in US treasury bonds. Economists are divided on the extent to which both the exchange rate and current account imbalances are a problem. At bottom is whether they are supply- or demand-driven – i.e., caused by a savings glut in China or spending binges in the United States and Europe. Max Corden (2007) expresses the view of most economists that trade deficits and surpluses can be perfectly rational phenomena expressing savings propensities of different countries, their actual and potential GDP, their level of competitiveness at present and in the future, and even demographic conditions. Current account deficits and surpluses reflect inter-temporal trade: currently produced goods and services in return for financial claims that can be exchanged for goods and services in the future.

For some, the solution is for China to boost the value of the yuan and increase domestic demand, something easier said than done. At China’s stage of development, overcoming the natural penchant of people to save for their old age and rainy days will take time. China can adopt more modern tax, social, and related policies that will accelerate consumer spending, lower levels of savings, and encourage more productive investment. It will take time, however, to ensure growth in the necessary institutions from banking to retail that will encourage such changes in behaviour. Even so, the rise in consumer spending over the past few decades should not be dismissed. The coastal urban centers now boast shopping centers and consumption patterns that rival those in advanced industrialized countries, creating social tensions for those not yet able to join this consumer revolution. Over time, as has happened in other countries, domestic demand will increase, particularly as the population ages and savers become spenders, albeit probably not quickly enough to satisfy US and other critics. Given Japan’s negative experience with US pressure to adjust its exchange rate in the 1980s, Chinese authorities are understandably reluctant to accede prematurely to US demands.

The oft-repeated charge that global corporations are moving capital and jobs to low-wage countries such as China at the expense of jobs and investment in North America and Europe is also simplistic and misleading. The large majority of outward foreign direct investment from OECD countries still goes to other OECD countries. To quote Daniel Griswold, “That’s where the rich customers live, where the workers are best educated, where the courts work and where trade and investment move freely” (Griswold 2004). Greaney and Li find that “Japanese and American investments in China have grown very rapidly in recent years, but from low initial levels, so these investments in China still represent less than 10 percent of outstanding FDI stocks for Japan and less than 3 percent for the US, even with Hong Kong investments included.” (Greaney and Li 2009:624).

It is also important to look beyond the short-term appeal of low labour costs. The net effect of FDI in China and elsewhere is to raise local wages and working conditions, move people up the economic ladder, and accelerate creation of a middle class of skilled workers, managers, and professionals, i.e., future consumers of globally produced goods. Short-term dislocation – or creative destruction in Schumpeterian terms – has always been the price of this kind of economic progress. Moreover, total OECD manufacturing output continues to increase. China is not replacing gross OECD output but is allowing manufacturers to continue to reap productivity gains by moving labour-intensive, less productive areas of activity offshore to China and to its suppliers of intermediate goods in the rest of Asia, and then importing finished consumer and producer goods from China, a net economic benefit to both sides.

China’s relatively weak regulatory system – a matter more of lax and discretionary enforcement and corruption at local and provincial levels rather than of inadequate legislation – has given rise to serious problems resulting from the production of shoddy and even dangerous goods. Local suppliers have been responsible for the delivery of inputs that have undermined confidence in Chinese-based production by major global firms. Chinese fakes, counterfeit products, and dangerously adulterated products are as much a problem for Chinese as for western consumers. As such, Chinese attention to this problem will increase, if not due to WTO commitments then due to lack of investor confidence and growing social and environmental problems. The prosperity flowing from the past three decades will need, in part, to be devoted to more uniform, transparent, and reliable enforcement of Chinese regulatory requirements. For those who have short memories, similar concerns were expressed about shoddy Japanese, Korean, and other products. China is experiencing the same phenomenon but appears to be moving up the quality ladder more quickly than Japan, Korea, and others did during their transformation.

China’s record on human rights is another area of western concern, and rightly so. China remains a totalitarian state and dissenting voices that threaten the control of the communist party and the central authorities are ruthlessly stamped out. That being said, the quality of life of most Chinese citizens has improved immeasurably over the past thirty years. The standard of living has improved, and the range of available consumer products has greatly increased. Private property rights are gradually being recognized. Newspapers and journals have proliferated. Access to the internet, while subject to censorship, has become widespread. Dissent and fierce internal discussion is not uncommon, although subject to the overall caveat of staying away from dissent and comment that the central authorities consider threatening. Foreign travel is now allowed for most Chinese, and internal passports are now enforced more flexibly, a source of both corruption and more freedom. Most urban residents are now responsible for finding their own jobs, accommodation and transportation on a competitive basis. But there remain limits that would be intolerable in a western democracy. Philip Pan points out:

Having tasted freedom, having learned something about the rule of law, having seen on television and in the movies and on the internet how other societies elect their own leaders, the Chinese people are pushing every day for a more responsive and just political system. The party has struggled to adapt and sometimes retreated in the face of such popular pressure, but it has not yet surrendered, not even close. (Pan 2008: xvi)

This pressure will only increase as prosperity increases and spreads further inland. To date, China’s leaders have kept the lid on and succeeded in nurturing prosperity in the absence of political freedom. As Pan also points out, “prosperity allowed the government to reinvent itself and to win friends and buy allies, and to forestall demands for democratic change. It was a remarkable feat, all the more because the regime had inflicted so much misery on the nation over the past half century.” (Pan 2008: xiv) How long this can continue remains one of the great questions facing China and the world. Direct criticism by foreign governments of this fault line, however, has proven counter-productive, as Prime Minister Stephen Harper appears to have concluded. Chinese authorities like to point to the many developments outlined above and to contrast their pragmatic approach to that of the failed communist regimes in Europe and to that of many other developing countries. The direction of change is clear, indicating that with greater prosperity will come more pressure to loosen the bonds further.

A leading concern among Canadian commentators is that Canada is losing out to others in gaining a place in an increasingly attractive market. Various econometric and other studies (Goldfarb 2008, Tiagi and Zhou 2009, Burton 2009, Chen 2010, CCC 2010) purport to show that Canada is underperforming in its economic relations with China, particularly relative to Australia. This concern reflects, in part, a deeply embedded longing among some Canadian analysts for a trade diversification strategy. It also suggests that the Chinese pie is finite and Australia’s gain is Canada’s loss. As the above discussion suggests, the Chinese economy is large enough to provide room for Canadian traders and investors, despite the early gains of Australians and others.

In any event, some perspective suggests that this “problem” may be exaggerated. Over the past decade, China has been Canada’s fastest-growing trading partner, albeit from a relatively small base, growing at a rate ten times faster than trade with the rest of the world. The pattern of growth has been similar to that experienced by the United States. On a per capita basis, nominal Canadian and US import and export values with China are similar. In both cases, the import-to-export ratio is roughly four to one. On a per capita basis, Canadians consume more Chinese goods than Americans and also sell more goods to China, suggesting that Canadian propensity to trade is slightly higher, but that price and geographic factors are dominant in both cases. Both Canada and the United States export primarily food and

industrial materials and import primarily finished consumer goods.

Globally, Canadian per capita exports of goods are roughly three times larger than US per capita exports, while Canadian per capita imports are slightly more than twice US levels. Once cross-border Canada-US trade is taken out of the equation, however, Canadian and US per capita trade is very similar.

Like Australian firms, Canadian resource companies have benefited enormously from the surge in resource prices. Statistics Canada’s Steve Grunau concluded in his study of Canada-China trade that:

… the Asian giant is buying Canadian products at a record pace. Since most Canadian firms do not specialize in manufacturing machinery or the kinds of components that Chinese factories assemble into finished products, they

haven’t been significant sources of Chinese imports from Canada. Rather, the study shows that Canadian businesses have achieved strong sales growth in other areas of high Chinese demand such as natural resources. Exporting companies in niche resource industries are benefiting the most. … Growing demand in China for raw materials to fuel its export industries and satisfy rising domestic consumption has raised global commodity prices. This has increased revenue in Canadian resource industries such as metals by increasing the value of exports not only to China, but also to major customers such as the United States. (Gruneau 2006:3)

In another Statistics Canada study, Ryan Macdonald considered the impact of China’s demand on the Canadian economy and concluded:

The adjustment that Canada underwent in response to the China-induced price changes looks, at first blush, like ‘Dutch Disease’– a situation where a resource boom leads to an appreciation of the national currency and a widespread reduction in manufacturing output. However, manufacturers in Canada adjusted to the competition from Asia by re-orienting to produce more durables and less non-durables (where competition from emerging nations is particularly strong). At the same time, Canada’s terms of trade improved as commodity prices increased, raising the purchasing power of Canadian incomes. In fact, the 19.0 percent increase in the terms of trade between 2002 and 2007 helped lift real income enough to support more consumption and investment in the face of rising energy prices. As a result, from 2003 to 2007, Canada went through a period that we recently characterized as ‘China Syndrome’ rather than ‘Dutch Disease’ (Macdonald 2008; see also Macdonald 2007).

Not only has the emergence of China as a major player in global trade improved Canada’s terms of trade, it has also contributed to a marked diversification in Canadian trade patterns. Diane Wyman points out that “while diversification may not be an end in itself, the recent shift to increased trade with the rest of the world has been well-timed, given the onset of the housing-induced slowdown in the US. … Export growth to countries other than the US has picked up momentum and export share. … This trade diversification may be contributing to the current decoupling of the US and Canadian economies. Certainly it has provided growth opportunities for several provinces whose exports to the US had weakened” (Wyman 2007:3.6-3.7 and 3.10-3.11). Her colleague Francine Roy adds: “Our imports have diversified away from the US, mostly due to increases from China which has made inroads into many of our consumer and investment goods. But some of the growth in China is illusory, reflecting its role in assembling parts manufactured in other Asian countries” (Roy 2006:3.8).

Finally, various federal, provincial, and private sector initiatives over the past decade seek to improve the infrastructure required to increase trade with China. Canada’s Asia-Pacific Gateway and Corridor Initiative, for example, is geared towards advancing Canada’s capacity to act as a conduit not only for Canada-Asia trade, but also for positioning Canada as a transportation hub for transpacific value chains involving US, Canadian, and Asian partners. Enbridge’s proposed Northern Gateway pipeline from Alberta to Kitimat, BC, to carry bitumen for export to Pacific markets has gained more interest in the face of US opposition to the exploitation of the oil sands and reluctance to approve TransCanada Pipelines’ proposed Keystone XL project. As these and other projects mature, the ability of Canadian firms to transact business in the Asia-Pacific region should increase substantially.

Implications and Challenges for Canadian Policy Makers and Business Leaders

In 1985 Canada made an historic decision: to negotiate a free-trade agreement with the United States (CUFTA). The decision was well grounded in the patterns of Canadian trade and economic development over the post- war years but sought to strengthen public policy provisions that would enhance Canadian firms’ ability to participate more effectively in a much larger and more integrated North American market. In response, cross- border trade and investment grew rapidly, underpinning strong growth in the Canadian economy. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which incorporated Mexico into the mix, consolidated the gains made in the CUFTA.

Canada’s decision in 1985 was consistent with a broader societal recognition that economies do best when there is a clear division between the roles of public policy and private initiative. Public policies that ensure equal opportunities for consumers and producers alike work much better than those that seek to push the economy toward short-term, politically fashionable patterns. Public policies that provide an open, enabling, competitive market environment, that work with, rather than against, market-based preferences, and that limit direct government intervention to market failures have a much higher success rate in democratic societies than dirigiste policies. The Canadian economy is much more open and competitive today than it was thirty years ago, although there remain pockets of protection reflecting the policy preferences of an earlier era.

Canada’s trade policy choice in 1985 reflected recognition of the dynamism of the US economy, the waning prospect of Europe’s ever emerging as anything more than a specialized, limited regional market for Canadian suppliers, and frustration with the slow pace of multilateral trade negotiations in Geneva. At the time, there was also some hope that stronger Canada-US ties would create a better platform from which private firms could pursue emerging markets in Latin America and Asia. The Latin American market did not develop as many had hoped, despite some early hopeful signs and efforts to build stronger institutional ties. The Asia-Pacific market, on the other hand, took off with a dynamism that few had anticipated.

The dynamism in the US economy, so evident in the 1990s, slowly waned as the US faced a growing list of domestic and international problems and political leaders seemed unprepared to take the tough decisions needed to put the economy back on track. For Canada, the initial surge in bilateral trade and investment reached its peak in 2000. Since then, trade and investment have stagnated. Various factors contributed to this stagnation, including the housing and financial crises, the thickening of the border following the outrage of 9/11, the lingering recession of 2008, and the globalization of production. NAFTA partners have failed to address these and other emerging issues, particularly the major structural changes in the global economy discussed above. The US market will eventually recover, as will bilateral trade, but neither is likely to regain the dominant role both enjoyed in the 1990s. Canada will need to continue to press US officials to resolve the growing list of bilateral issues on the agenda, but under current circumstances, both Canadian business leaders and policy makers also need to consider alternative and complementary opportunities beyond North America.

The evolution of the global economy has driven China, East Asia, and North America into an interdependence that is stronger than with any other parts of the globe. Transatlantic links are now of a distinctly lower order than transpacific ones. Canadian policy needs to catch up to this reality. As the above analysis suggests, overtures with a challenging but rising Asia will in the long run prove more rewarding than those with a deeply troubled and declining Europe.

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, established in 1993, sought to stimulate transpacific ties through a range of government initiatives. Rather than negotiating a regional accord, governments opted for concerted unilateralism as the key to more liberal trade and investment conditions, reflecting Asia’s preference for ambiguity and consensus rather than structure and rules. This government-led initiative soon ran out of steam. In its place, private businesses forged their own ties and opened markets by means of the production networks and value chains discussed earlier. To capture a share of this activity, governments throughout East Asia took the steps necessary to welcome foreign investors and become players in this world of integrated production. Even India, long one of the world’s most reluctant liberalizers, introduced reforms that encouraged firms to locate slices of activity in India, particularly the services dimension of global production networks.

Governments on the Eastern and Southern fringes of the Pacific have now begun to catch up to the reality of this Asian dynamism by looking at ways to consolidate business ties with stronger governance provisions. New Zealand and Australia led the way with bilateral overtures and arrangements followed by the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) initiative launched by Chile, New Zealand and Singapore in 2002. At the 2011 APEC Summit, Canada and Japan expressed their interest in joining the initiative, bringing the potential number of participating governments to 11. China has to date indicated no interest in joining, but is watching developments closely.