A New North Star

Canadian Competitiveness in an Intangibles Economy

About the Authors

Robert Asselin is a PPF Fellow. He joined BlackBerry in 2017 as Senior Global Director, Public Policy. In 2017, he was appointed Senior Fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. From 2015 to 2017, he served as Policy and Budget Director to Canada’s Finance Minister. From 2007 to 2015, Mr. Asselin was the Associate Director of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. In 2014, he was a Visiting Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Mr. Asselin was a policy adviser to Prime Ministers Paul Martin and Justin Trudeau.

Sean Speer is Fellow in Residence at PPF and a sessional instructor and Senior Fellow in Public Policy at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. He served in different roles for the federal government including as senior economic adviser to former Prime Minister Stephen Harper. He is also an associate fellow at the R Street Institute in Washington, D.C. and has been a Senior Fellow for fiscal policy at the MacdonaldLaurier Institute.

Foreword

By Edward Greenspon

The New Frontiers of Competitiveness

As Robert Asselin and Sean Speer point out in this report, competitiveness resides at no fixed address and never stops to rest. It is a dynamic process and so Canada’s ability to create goods and services the world wants and get them to market at attractive prices must be continuously re-evaluated against changing circumstances and the shifting capabilities of other nations intent on eating our lunch.

Asking how competitive we are in relation to China would have been ridiculous 40 years ago. But China first learned to feed itself, then became the factory to the world, and now sets world-leading standards when it comes to such 21st century technologies as solar power and artificial intelligence. Conversely, at the beginning of the 20th century, it made sense for Canada to measure its competitiveness against Argentina, an immigrant and agrarian nation like ours that exported similar goods to the world and enjoyed comparable prosperity. Over the succeeding hundred years, Canada’s more enlightened politics and policies (and proximity to the United States) allowed our standard of living to leap far ahead.

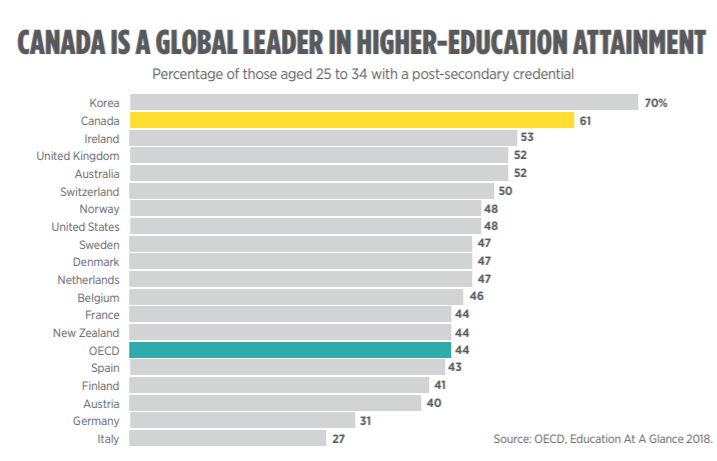

As a result, Canadians have superior housing, health care and higher education (Canada ranks second best in the OECD; Argentina is third worst). A nation’s competitive standing should never be discounted as esoteric or elite. It has real meaning for real people — justifying its demand for constant attention.

That’s true in normal times, and even more so in today’s abnormal times. A series of rapid and far-reaching changes to global, national and regional economies, driven largely by technology but also by demographics and geopolitics, are forcing us to rethink core assumptions as to what makes a nation competitive. Newly emerging factors of economic success are barely recognized, never mind discussed. But they could make a tremendous difference to the welfare of the nation and its citizens.

Many observers argue the changes underway are the most sweeping since the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, which ushered in a feverish period of migration from farm to city and transformation from craft economy to capitalism. The social impacts were massive. Wages stagnated for a couple of decades even as productivity soared and reformists ultimately introduced historic educational and social reforms while trying to stave off a radical response. Eventually, society adjusted and economies grew, but not without heartbreaking losses of liberty and livelihoods.

Among the Public Policy Forum’s five major areas of concentration are the economic and social determinants of growth, policy-making in an age of disruption, and the future of work. We believe as a fundamental principle that faster growing economies have a better chance of delivering prosperity, security and social cohesion to citizens than slower-growing ones. But if significant percentages of the population are excluded from this progress, it eats away at the necessary political consensus at the heart of successful democracies.

A series of rapid and far-reaching changes to global, national and regional economies — driven largely by technology but also by demographics and geo-politics — are forcing us to rethink core assumptions about what makes a nation competitive or not.

Growth without sustainability is no longer ecologically feasible; sustainability without growth is unlikely to be politically feasible. The unenviable task of figuring out new ways forward falls to public policy thinkers and practitioners. Wanting to understand how these new challenges and potential solutions impact Canada’s economic dynamism and political cohesion, Robert and Sean set out to consider both the ongoing classic factors of Canadian competitiveness (deficits and debt, interest rates, taxation, foreign investment, etc.) and the newer drivers (data, intellectual property, design, brands, etc.) associated with what some have begun to label the intangibles economy.

What is an intangibles economy? It is one that favours intellectual property over physical assets. A research facility for the autonomous vehicle becomes a more valuable asset than an assembly plant for cars in this patents-over-plants world. It is also an economy of more pronounced winners and losers, income inequalities being just one manifestation. To the victors go tremendous spoils since the advantages conferred by IP and data tend to a) create dominant market positions and b) feature near-zero marginal costs for each additional customer. As Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel has observed, expanding from one to two yoga studios involves the cost of new space and more instructors whereas Facebook, Google or Netflix can add new customers with no additional burden. Robert and Sean provide some startling figures about the values financial markets place on intangibles versus tangibles.

In looking to understand the components of a contemporary competitiveness agenda, we purposely reached for a pair of writers with attachments to one or another of Canada’s historic governing parties. Robert has worked in an economic advisory capacity to a Liberal government; Sean to a Conservative government. As they state, multi-partisanship is essential since any competitiveness strategy worth its salt must be grounded in a long-term perspective and therefore has to persist through several economic and political cycles.

Despite the hyper-partisanship of our era and the depths of disruption, the authors are ultimately optimistic about the possibilities. They note that within a half-dozen years of the divisive 1988 free trade election, a consensus in favour of such free trade agreements had developed among the major political parties. The Mulroney, Chrétien, Martin, Harper and Trudeau governments all pursued complementary goals.

In Part Two of this report, Robert and Sean have divided their analysis into three main sections. The first deals with the classic drivers of competitiveness, the ones that spring from the early economic thinkers and have picked up ideas along the way from the likes of John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman. This is the stuff of the competitiveness discussion as we’ve known it. Getting these fundamentals right remains absolutely necessary.

The rise of the intangibles economy requires that we test old assumptions and are open to new thinking.

Canada’s economy cannot afford complacency in this new economic era.

Yet it is their second section, competitive policies crafted with the intangibles economy in mind, where the most challenging actions lie, for the very reason that everything is new and some of it may test nostrums with which we have grown comfortable. It is starting to be argued in some quarters that we need to look at matters such as free trade, foreign investment, competition and employment policies through the lens of the technological age. Do they confer the same costs and benefits in both a tangibles and intangibles economy? At the very least, this is uncharted territory for policy-makers and demands a deeper understanding of quickly evolving industries and more intense public discussion than it has received to date. We don’t want to be caught fighting the last war.

The third section deals with the critical common ground between these two worlds, the ever-greater need to nurture and develop human capital. Talent and skills, from executive suites to the shop floor, have long been vital components of economic success or failure. Even when a nation is blessed with forests, minerals and energy abundance, and access to the U.S. for manufactured goods, human ingenuity is part of the mix. When ingenuity itself — the capacity, for instance, to develop unique IP or data sets as a basis for ongoing wealth creation — becomes the driver of competitive advantage, the quality of one’s human infrastructure becomes even more consequential.

With this paper, PPF hopes to broaden the terms of the competitiveness debate in Canada as the country seeks a new policy consensus for a radically changing set of economic circumstances. The work would not have been possible without the contributions of our sponsors: RBC, Business Council of Canada, Teck, University of Toronto, Universities Canada and McCarthy Tétrault; the PPF team, including Chris Cornthwaite, Daniel Pujdak, Jonathan Perron-Clow, Masha Kennedy and Bev Hinterhoeller; and, of course, the two PPF Fellows who devoted their time and deliberation to puzzling over these issues, Robert Asselin and Sean Speer. I thank them all.

Edward Greenspon

President & CEO, Public Policy Forum

Summary of Policy Considerations

Introduction

In the world of policy and politics, short-termism and complacency are difficult to resist. They trump partisanship. They trump best intentions. Pressure mounts on any government or political party to respond to immediate issues and keep an eye fixed on the four-year election cycle. Both of us observed these demands in our respective positions as economic advisers to national governments.

The problem is that reactive governance is inconsistent with the mix of long-term policies required to promote broad economic participation and growth. For a competitiveness agenda to maintain and raise Canadians’ quality of life, it demands discipline, focus and a vision that extends beyond the election cycle. It thus requires a multi-partisan commitment. A change in government may naturally result in new preferences and priorities, but it should not cause us to lose collective sight of the common bases of competitiveness, productivity and jobs, and the greater opportunities and outcomes they produce for successive generations.

Thus this report leans neither left nor right. The analysis and recommendations do not emerge from a liberal or a conservative perspective, but a bi-partisan one. We take a hard look at the particularities of Canada, including the blessings and curses of being an open economy nestled next to an increasingly wilful superpower that is home to many of the new generation of global technology superstars. On top of the ever-present regular competitiveness issues, Canada, like others, faces a set of new challenges emanating from rapidly changing geopolitical and technological realities. Yet our country is also blessed with advantages conferred by both nature and a legacy of good policy choices, especially in terms of education, immigration and social cohesion.

It is an ongoing challenge to keep coming up with the right answers even as the questions become more perplexing and complex. This paper represents our attempt — in conjunction with PPF — to identify the opportunities and challenges on the road ahead and offer directions to guide policy-makers as they navigate Canada’s economic future.

Our overall assumptions for this paper are as follows:

- A competitiveness agenda must be fixed on a “north star” that represents a clear, multi-partisan set of long-term economic objectives. This is the best means to ensure policy-makers remain focused on the overarching goals of competitiveness, innovation and productivity.

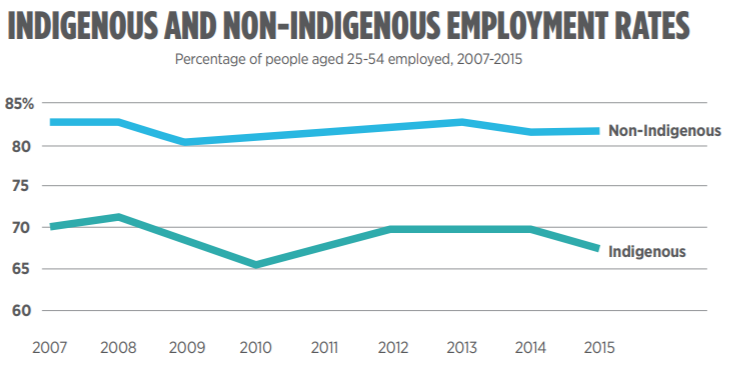

- The process of identifying these objectives and developing the policies to achieve them must be inclusive, including voices and perspectives from different industries, regions and backgrounds. We submit that one of the principal reasons these issues have not had greater public resonance is that most Canadians have felt excluded from the conversation and do not understand what it means for them and their families. The question of long-term economic competitiveness is one of fundamental importance for all citizens. It cannot be confined to a debate among elites.

- The rise of the intangibles economy (what has been described as “capitalism without capital”) is a game changer. Canada’s current policy toolkit is mainly designed for a world of tangible assets, where capital and labour are the main factors of production and investment and trade raise everyone’s boat. The growing trend towards intangible assets, such as data, brands and IP, requires that policy-makers re-evaluate, refine and improve our basic assumptions about economic competitiveness and the best mix of public policies to support it. This does not mean discarding foundational ideas about markets and openness. But it does mean questioning old assumptions and augmenting them with emerging thinking about new factors at play and the “winner-take-all” nature of the intangibles economy.

- The tangibles economy and the intangibles economy share an interest in the development and deployment of human capital. Canada has done well relative to other nations but, again, new issues and different points of emphasis are coming into play in a fierce, global competition for talent. Importantly, then, training, attracting and retaining human capital is the one major policy area that bridges these two paradigms.

There are other issues and topics that must inform and shape a pro-competitiveness agenda for Canada. Climate change and the ongoing transition in the energy sector are certainly among them. We recognize that we have glossed over some matters in order to concentrate on under-explored areas badly in need of increased public debate. Our goal is to inform a more elaborate discussion about how policy-makers ought to think about both the old and new drivers of competitiveness, and how Canada’s overall policy framework needs to evolve and adapt in light of changing circumstances.

What is competitiveness and why does it matter?

Policy-makers, media and other commentators frequently talk about economic competitiveness. One could not read the editorial pages or watch marketrelated news in 2018, for instance, without encountering a discussion or debate on the topic. The whole policy dialogue was often reduced, unsatisfactorily, to the single variable of corporate taxation.

Canadians may instinctively understand that competitiveness is related to job prospects in their communities or the size of their paycheques. But they have not generally been invited into these larger conversations. The concepts can seem abstract. The policy prescriptions can sound technocratic. And the discussion can be insular — involving a small number of the “usual suspects” in a continuous loop of deliberation among themselves.

The development of such a long-term, inclusive and participatory competitiveness agenda starts by addressing some basic questions.

- What is competitiveness?

- Why does it matter?

- How does Canada perform?

- How can we do better?

- What will it mean for ordinary Canadians?

Careful and deliberate answers to these questions are essential ingredients to well-designed, evidence-based policies and the necessary multi-partisan commitment to sustain them. There is arguably no more fundamental question that Canadian policymakers must address. A dynamic, competitive and growing economy represents the foundation for all other policies, whether they target broad-based opportunity and participation or income distribution and equity. Social goods are built on strong economies.

Competitiveness is, by definition, a dynamic process as different jurisdictions strive to give themselves a policy edge in order to enhance investment and productivity and to create jobs. It is thus a never-ending process involving a multiplicity of interacting policy levers and tools.

Why competitiveness matters

The World Economic Forum defines competitiveness as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country” — a description we find as useful as it is under-utilized.

A competitive economy is a productive one. More productivity leads to greater prosperity, opportunity and higher living standards.

This point cannot be overstated. Competitiveness matters because it contributes to greater productivity, and greater productivity drives economic growth and rising incomes, which in turn allows for higher living standards, more sustainable social programs and greater social mobility. The Canadian economy is built on selling more goods to the world than we consume. That is the ticket for a relatively small population to run with the economic leaders. This is neither a theoretical point nor a subject of concern only to business executives or institutional shareholders. Rising incomes are a key economic measure for the satisfaction of Canadian households, whether in our hometowns of Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Quebec and Thunder Bay, Ontario, or anywhere in Canada. Competitiveness is

the major determinant between economic growth and economic stagnation. It is the foundation for successful communities and nations. Addressing it is not an issue of left or right; it is necessary and expected across political divides.

This, of course, does not mean that the processes of innovation and rising productivity produce universal benefits, particularly in the short term. An emphasis on efficiency and dynamism will invariably cause short- and even long-term dislocation for certain sectors, regions and people. It is essential therefore that a corollary of any competitiveness agenda must be a credible plan of transitional adjustment support for those affected. The development, design and implementation of such a plan is beyond the scope of this paper. But we cannot overemphasize how important it is that these two policy agendas work together. The concept of “creative destruction” recognizes that innovation and dislocation are inseparable. The same goes for public policy. This is essential for sustaining public support for dynamic capitalism and protecting against rising economic and social inequality. Canada has benefited from broad political support for different forms of redistributive policies. Going forward, it is imperative for the general good that a well-functioning safety net remains a central

preoccupation for policy-makers.

As we mentioned earlier, Canada’s economic competitiveness has been the subject of great debate in recent months, but this discussion has focused on short-term actions and individual policies. Yet a competitiveness agenda is ultimately about a mix of public policy choices over the long term. There are no silver bullets.

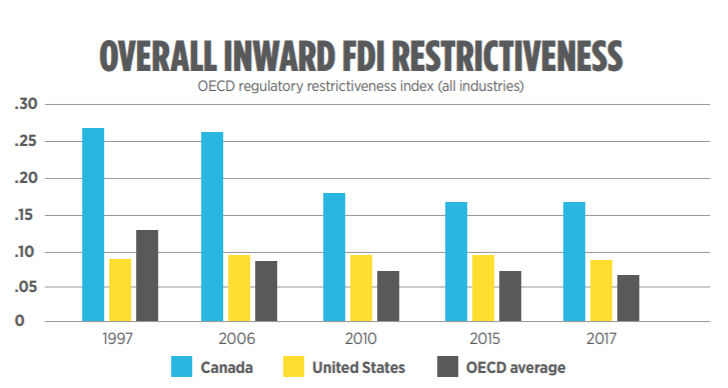

As an example, one aspect of Canada’s competitiveness quandary is our stagnant business investment, including Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Slow business investment is a multi-faceted problem. There is no federal or provincial policy lever that will singularly catalyze large-scale private sector investment. It will require a careful and deliberate agenda involving various policy levers, including possible tax changes, regulatory reform, investments in productivity-enhancing infrastructure, and so on, to restore higher levels of business investment in the country.

An obstacle to such an agenda is that the benefits and costs do not materialize in the short term. For instance, stagnant or declining business investment may only have minimal effects on the short term. Economist Frances Donald describes the economic challenge as eventually “com[ing] up against a speed limit it [the economy] cannot pass.” Low business investment ultimately catches up. Think of an under-capitalized auto plant that can sustain itself now but fails to compete for new global mandates in the future. Or an oil pipeline that can move current supply but cannot handle future growth. Employment and income may be unaffected in the short term. Yet, delays or ignorance will invariably come home to roost as Canada reaches the economic speed limit that Donald describes. Today’s policy choices can produce outcomes that lag but eventually they show up.

Policy-makers must think ambitiously about positioning Canada for long-term competitive advantage in an age of rapid technological and economic disruption. While debates on how best to achieve a competitive economy or how to distribute its fruits should be vigorous, it serves the country best when political parties and private players agree on the essentials of competitiveness and their importance.

One obstacle to reaching this consensus is a tendency to think of economic competitiveness as a static question. This is a mistake. Competitiveness is a dynamic process involving different economic cycles, different policy areas and different policy instruments. It requires a long-term vision that is continuously refined and strengthened to advance key objectives related to investment, productivity and living standards. The idea of a “journey rather than a destination” may be clichéd, but it is important for policy-makers to resist the urge to ever think the dossier is closed and declare “mission accomplished.”

Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to the intangibles and data-driven economy, which is rapidly producing new factors of competitiveness. These new drivers are creating a fresh paradigm, one that obeys a different set of rules than the conventional economic thinking that has underpinned policy-making the last few decades. New perspectives are challenging basic assumptions about how to think about competitiveness and the right set of policies to sustain it in a tech-driven economy.

The rise of this intangibles economy could have sweeping policy implications. Understanding its effects on public policy can be difficult for political actors. This debate began in the technology world and is only now starting to spill into the public domain. The basic premise is that the new economy will no longer be mainly fueled by capital assets such as equipment, machinery and physical plants and instead will be increasingly driven by intangible assets such as domain names, service contracts, computer software, data and patented technologies.

The intangibles economy is principally about accumulating assets that produce continuous streams of rents with low or no capital requirements after initial investments, and therefore have practically zero marginal costs. Conventional economic thinking is poorly equipped to account for these non-rivalrous assets that can be consumed or possessed by multiple users for multiple purposes. Think of data, for instance. A single dataset can fuel multiple algorithms, analytics and applications, and so the data owner operates with minimal costs and with greater chance of dominating a market.

Famed Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel has pointed out that the new economic set of rules is unlike those that have existed previously. For someone who owns a yoga studio, for instance, expansion entails higher fixed costs in the form of additional premises or instructors. In contrast, the marginal cost of an added user of Google or Twitter is essentially zero. This is what is meant in the technology world by “scalability.”

A new, more zero-sum economy, according to this perspective, requires that policy-makers must both revisit traditional economic policies (such as IP and a foreign investment regime) and enact policies related to new and emerging questions (such as data governance and ownership.) It has been audaciously argued that “neoclassical economic policy has yet to come to terms” with these economic changes and that “a coherent framework has not emerged.” Add the emergence of AI and growing questions about the “future of work,” and policy-makers face a new paradigm when it comes to Canada’s competitiveness and its long-term economic prospects. Most examinations of competitiveness stick with the classic knitting of taxes and deficits and access to markets — all valid, even critical, to a country’s economic success. In this paper, we aim on top of that to expose the opportunities and challenges associated with the intangibles economy. It behooves policy-makers to rethink and refine conventional policies and enact new ones to set Canada on a long-term path for competitiveness, innovation and productivity.

How Canada is Performing

The purpose of our analysis is not to render judgments about Canada’s economy in the here and now. There is no doubt that the Canadian economy has been performing relatively well compared to various others since the last global financial crisis. But this type of judgment can, in our experience, reinforce a political predisposition to complacency.

The onus must be on policy-makers to look beyond today’s headlines and develop a competitiveness agenda that accentuates Canada’s economic strengths and minimizes its weaknesses for a changing world over the long term. Competitiveness must be at least three-quarters about tomorrow rather than today.

Canada must come to grips with both huge opportunities and challenges on the horizon. It has a stable political environment, an immigration system that enables fresh thinking and economic mobility, domestic safety and security, proximity to the U.S. market, and one of the best educational attainment rates in the world. But we also face significant challenges: an aging population, low levels of business investments (domestic and foreign), structural impediments to globally scaled firms, regulatory obstacles that go well beyond pipeline debates, and so on.

Take this together: Canada is losing the advantage of a young population, large injections of foreign capital, global demand growth for (or domestic supply of) our goods, and of productivity gains in areas of increasing strategic importance. The resulting lack of globally competitive firms condemns us to falling disastrously behind. The demographic trends alone are squeezing labour markets and talent pools while depressing tax revenues and increasing social and health spending. This needs to be turned around through a sustained policy agenda that enhances our competitiveness.

Notwithstanding Canada’s most recent economic success, our country faces an urgent long-term growth challenge. In the last 2019 budget, the

Government of Canada’s five-year growth forecast for 2018-2023 shows an annual average of 1.8% GDP growth, which is far below the rate of 3% observed over the previous 50 years.10 What this means for succeeding generations is rather than doubling Canada’s wealth every 24 years (almost four-fold in a working life), it will be doubled every 40 years, a huge erosion in living standards and the capacity to finance redistributive and social programs.

So although the Canadian economy has performed relatively well, there are flashing caution signs that ought to be the subject of long-term concern. The main one is that the economy is not as productive as it should be. A failure to address this challenge will have long-term consequences in the form of less investment, fewer jobs, less wealth and diminished opportunity.

A long-term competitiveness strategy is therefore not just about corporate profits or global market share. It is about enabling more dynamism and growth in serving the cause of opportunity, jobs and prosperity for Canadian households across the country.

Canada’s Wake-up Call

As a high-expectations but mid-sized economy, Canada has always worked hard to shape international institutions and relations as a means to manage the risk of being sideswiped by agendas beyond our command. As a commodity-based economy, Canada relies heavily on a stable, rules-based trading environment in which global prices are based on market dynamics of supply and demand, and not on great powers throwing their weight around.

Canada is dependent on global pricing mechanisms, for better or for worse. Precipitous downturns in Alberta in the mid-1980s and in the mid-2010s as world oil prices collapsed illustrate that Canada is vulnerable to policy decisions and market dynamics far from home. Similar cases have occurred in copper, iron, lumber, and so on. Disruptions to the global pricing system by different economic and geopolitical forces have implications at home. Canada’s reliance on natural resources means it will be disproportionately affected.

The geopolitical tumult of the last 18 months or so has served as a real wake-up call regarding Canada’s vulnerabilities. Given Canada’s limited influence on the trends that we describe, policy-makers must maintain a razor focus on the aspects where our country can exert some level of control. Protecting, Canada’s wake-up call sustaining and strengthening Canada’s competitiveness is now more urgent than ever. The things Canadians collectively took for granted until recently — a reliable trading partner on our single land border, grounded in a regional trade agreement (NAFTA) and a liberal international trade architecture (WTO); our ability to get our resources to market and plug into integrated global supply chains that included China — have been subjected to a huge stress test.

Canada’s longstanding trade reliance on the U.S. has made it too comfortable. The Trump administration’s erratic trade policy, including the imposition of tariffs on Canadian aluminum and steel for “national security” reasons, has jolted Canada from its complacency and reinforced the case for trade diversification. Successive Canadian governments have sought to expand Canada’s trade network. The current government, for instance, deserves credit for signing and implementing the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), building on work started by its predecessor. Still, the numbers speak for themselves — in 2018, 74% of Canadian exports were still going to our southern trading partner.

Without U.S. leadership, the global order and international institutions upon which Canada relies are getting weaker. The international architecture largely founded after the Second World War is rapidly eroding. All the institutions created to manage an orderly globalization — including the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the G7 — are losing legitimacy and traction. The capacity for countries to come together and resolve global irritants, whether over classic issues such as trade or emerging challenges like data governance, has been weakened. The decline of global institutions and global dialogue represents a huge risk to the management of Canada’s economy and the economic interests of its citizens.

Then there is the U.S.-China rivalry. No matter its short-term ups and downs, it will have significant implications for the global economy in general and Canada in particular. It is not really about trade balances. It is fundamentally a technology war, driven in large part by a race for global leadership in an era where technology can confer huge economic and strategic advantages.

The Trump administration is determined to see U.S. companies reduce their reliance on inputs from China and limit the transfer of intellectual property, particularly in high-tech sectors and those related to national security. Even if the U.S. and China can resolve their current trade tensions, the U.S.-China relationship could escalate to a real schism between the two main economic superpowers, with the risk of disrupted global supply chains. Canada will be stuck in a difficult position between its largest and, by a large margin, second-largest trading partners. Navigating these tensions will have significant implications for Canada’s geopolitical and economic interests.

We highlight these global trends in large part to remind readers of the broader context in which Canadian policy-makers must develop and advance a competitiveness agenda. Global turmoil and disruption only reinforce the importance of an unremitting focus on enhancing Canada’s long-term capacity and consistency of actions to attract investment, enable innovation, and create jobs, wealth and opportunity.

A winner-take-all paradigm

As we have stated, there now exists a new layer of complexity to our relative economic performance. Canada is faced with a new generation of competitiveness drivers.

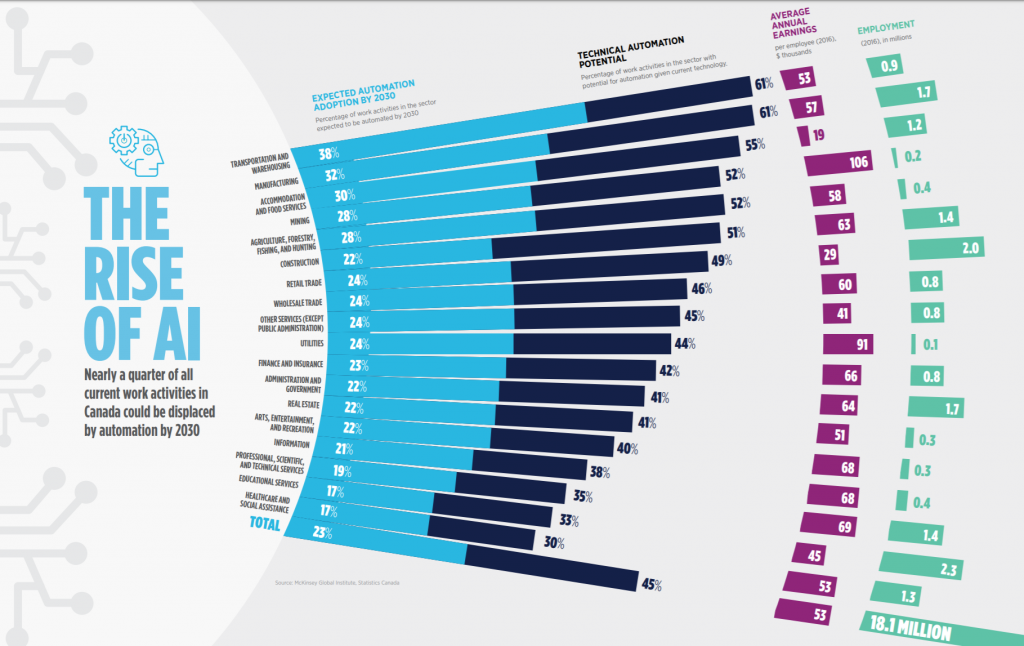

The global economy is going through a major transformation, sometimes referred to as the fourth industrial revolution. This refers to the explosion of new technologies and technological applications, such as artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, quantum computing or robotics, which are reshaping industrial processes and products, as well as how firms interact and compete.13 These technologies and their commercial applications have the potential to suddenly upend sectors, firms and workers.

This disruption is happening at lightning speed and labour markets are going — and will continue to go — through significant transitions, at an even greater pace to similar transitions over the last three industrial revolutions. The pace of this revolution is dramatic; some would say scary. The data-driven economy seems markedly different from the 20th

century economy, or what others have called “the production economy.” It can leave countries and firms in the dust if they do not adjust and adapt at

rapid speeds.

In large part, this velocity is driven by how scalable the intangibles economy is. Businesses with intangible assets can grow faster and bigger than those that lean on tangibles. A family-run taxi firm that owns a fleet of cars cannot scale as quickly and significantly as a ride-sharing app that owns no vehicles and yet leverages its platform and algorithms based on big data aggregation around the world.

Big data and artificial intelligence allow us to access and transform information beyond anything the human mind has ever imagined. Even more fundamentally, these tools add exponential power to those who control them. Public policy has a significant role to play in enabling and facilitating these transitions while helping people ride the technology-induced waves.

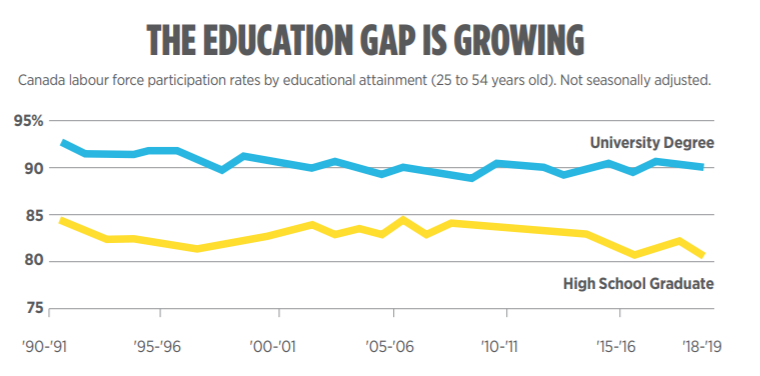

The fourth industrial revolution is further widening a growing opportunity gap between those with post-secondary credentials and those without. Routine work is being crushed by technology. Non-routine work is heavily rewarded. This phenomenon, described by some as “skills-biased change”, is producing an economy in which opportunities are increasingly bifurcated based on education.

Differing market outcomes based on education levels is not new. Education-driven differences in employment, income growth, job security, and so on have existed for some time. The chart below, for instance, shows a consistent labour force participation gap based on educational attainment over the past 30 years. But the gap seems to be widening. One example: the median annual earnings of working-age Canadian males employed in 2015 was $82,082 for those with a bachelor’s degree and $55,774 for those with high-school education — a gap of nearly 50%.

This polarization of labour market outcomes contributes to higher rates of inequality among people and geographies. High-skilled occupations are generally clustered in cities. Mid-skilled jobs tend to be located on the periphery. The result is increasingly unequal outcomes in society and the concentration of trade and technology induced dislocations in certain demographic groups, sectors, regions and communities. The consequences of these clusters of economic “losers” cannot be neglected. A failure to address their needs can cause people to question the utility of a dynamic economy and governments, and even express their disillusionment through radical politics, as we have observed elsewhere. Political instability, just like economic uncertainty, impacts competitiveness. It is imperative, therefore, that a long-term strategy incorporates a robust policy response to support those who are disrupted by “creative destruction.” Policy-makers must seriously think through a new human capital agenda to ensure that outcomes of the fourth industrial revolution are broad-based and inclusive. We will more directly address these issues in Part Two of the paper.

As important as these matters are, they are not the only or even the primary way in which the fourth industrial revolution is confounding policy-makers. The most significant may be how the interaction between technology and data is promoting largescale corporate concentration and a “winner-take-all” business model.

Canada has experienced corporate concentration in the past. The contemporary regulatory state was established in large part in the early 20th century in response to earlier bouts of corporate concentration. But the new experience seems both similar and different. Earlier episodes at least occurred in industries physically situated within sovereign jurisdictions. They were more easily subjected to policy measures. Today, there is an unprecedented convergence of wealth and power by a small number of tech giants based in the U.S. and China. The facts of their increasing hold on the economy speak for themselves:

- In 2018, while the U.S. share of global GDP was 24.2%, the U.S. corporate market share of global markets was 55%.

- In nominal terms, Google, Apple and Microsoft’s market capitalization figures (varying between $800 billion and over $1 trillion) are equivalent to the combined GDP of Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia.

- Since 2010, the cumulative total return of the S&P 500 — which comprises stocks issued by 500 large-cap companies and traded on American stock exchanges covering about 80% of the American equity market by capitalization — was 192%. In comparison, MSCI’s All Country World Index, the industry’s accepted gauge of global stock market activity, had a cumulative return of 47%.

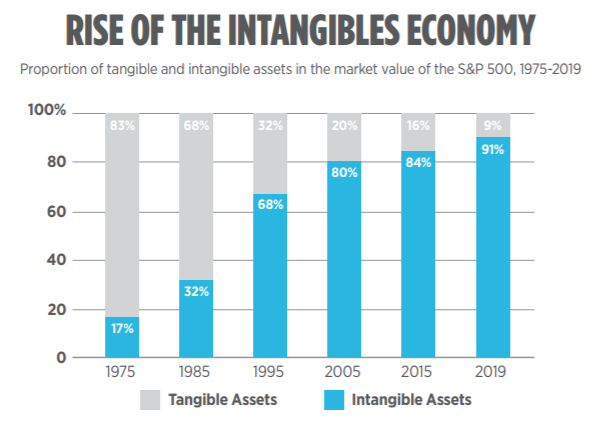

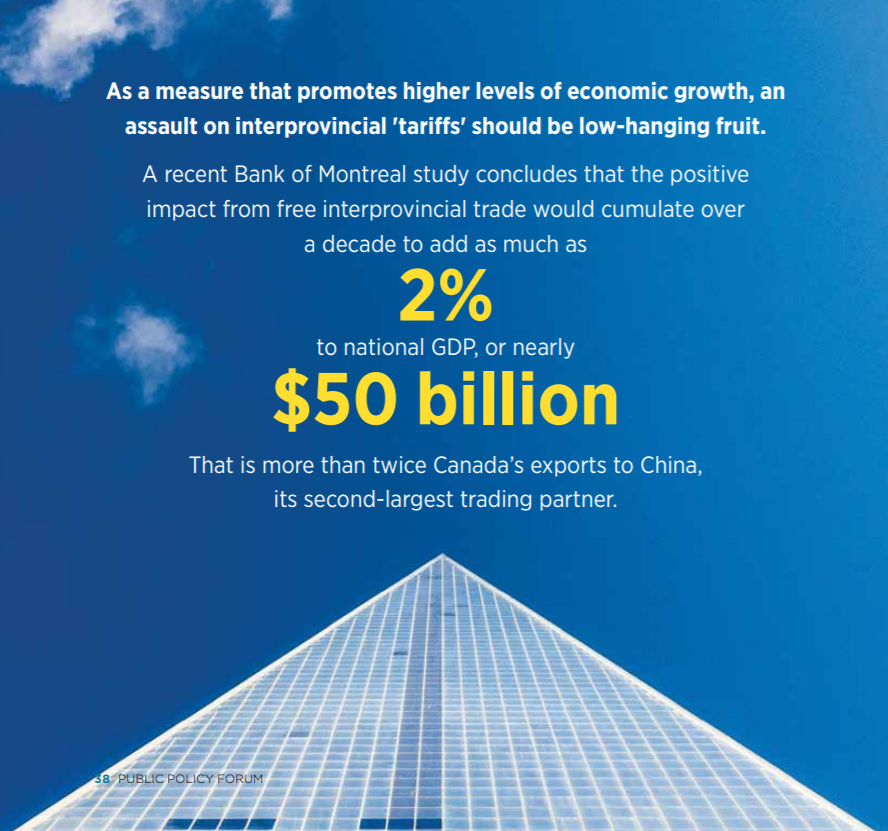

The S&P 500, in fact, is a telling barometer of how profound is the unfolding transition to a data-driven economy. In 1976, 16% of the value of the S&P 500 was in intangibles assets (i.e. brands, IP, data, etc). Today, intangibles assets comprise 91% of the S&P 500’s total value (see chart above). Together, the world’s five most valuable data-driven companies are worth well over $4 trillion (Canada’s annual GDP is about $2 trillion), but their balance sheets show only $225 billion is in tangible assets, or just over 5% of their total value. Increasingly, this is a radically different economy, with new commanding heights.

It is striking and disturbing how little we know about or are looking into these trends. We had difficulty finding a Canadian intangibles assets figure to compare with the S&P 500 number (something ultimately produced for us that will be discussed in Part Two of this paper.) Several public commentators who have started to look at these issues argue that the data-driven economy is fundamentally different than the production economy and that, therefore, the conceptualization of the role of government and public policy needs to change accordingly.

Traditional economics assume that mutual exchange at the individual, firm or country level involves mutual benefits, with both parties extracting value. Some argue that this historic insight does not apply to the collection and deployment of data by a small number of firms that quickly develop market dominance. The idea here is that large tech firms (such as Google, Amazon and Facebook) have the capacity to own such significant market shares that they can exercise sprawling influence on the marketplace — including with suppliers, workers, consumers, legacy competitors and even citizens. Mutual exchange can thus be replaced by large-scale monopolies with significant market power. The takeaway is that classical economics provides an incomplete framework to think and respond to dynamics of the data-driven economy. There is thus an urgency to come up with a game plan for our economic prosperity over the long term. In a recent blog post, Bill Gates offered a few insightful reflections from the 2017 book, Capitalism Without Capital, by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake. He argued that policy-makers need to ask fresh questions and adjust their economic agenda to reflect the new realities emerging from the intangible economy:

“Measurement [of intangible assets] isn’t the only area where we’re falling behind — there are a number of big questions that lots of countries should be debating right now. Are trademark and patent laws too strict or too generous? Does competition policy need to be updated? How, if at all, should taxation policies change? What is the best way to stimulate an economy in a world where capitalism happens without the capital? We need really smart thinkers and brilliant economists digging into all of these questions.”

We agree. It does not, of course, mean that all of the insights from classical economics can be dismissed. But it is incontrovertible that a long-term competitiveness agenda for Canada needs to engage the growing shift to an intangibles economy and the extent to which policy-makers must re-conceptualize policy assumptions about IP, taxation, competition, FDI and other areas. This interaction between old and new economies and the accompanying policy implications is the raison d’être of this paper. Canada’s competitiveness quandary transcends partisanship and political ideology. Whichever political party wins the next federal election will be faced with these questions and challenges.

We spoke earlier about our experiences in government and how difficult it is for policy-makers to resist the tendency towards short-termism. One solution is to set out a long-term economic vision that can serve as the government’s “north star.” A clear set of long-term objectives can inform individual policy choices and reforms, and keep policy-makers on track in the face of the inevitable pressures of unexpected developments or the political cycle.

Canada has been generally well-served by a north star that was broadly shared across the political spectrum, beginning first with the policies and institutions — domestic and international — of the post-war era and then, from the mid-1980s to the present, the basic market framework and accompanying public policy agenda envisioned by the 1985 Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada. Key parts of that agenda were subsequently adopted and advanced by Canadian governments of different political orientations.

But there are growing questions as to whether that north star set in the early 1980s — including its rote support for greater market reliance and a free trade agreement with the U.S. — still offers the best objectives under new geopolitical and technological circumstances. Do our main public policy actors at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal levels still have the right plans to lift the economy of today? The rise of the intangibles economy challenges the longstanding policy consensus. Concerns about climate change, income inequality and the future of work, as well as the most profound geopolitical changes since the collapse of the Soviet empire, are also causing people from across the political spectrum to ask new and equally profound sets of questions. With all this change, it is time to reflect upon a new north star.

We think of it this way: there is certainly a need to consider refinements to conventional pro-competitiveness, pro-innovation policies and the adoption of new ones in light of the emerging issues flowing from technological change. But Canada should not discard willy-nilly the ideas of economists and scholars who have studied the drivers of growth since Adam Smith’s seminal work nearly 245 years ago. The time-proven standards, such as smart taxation and fiscal policies and physical access to markets, will live alongside the rising challenges of the intangibles economy for the foreseeable future.

Policy-makers will therefore need to strike the right balance as they reset Canada’s north star toward a contemporary policy agenda strengthening long-term competitiveness. And they must incorporate the opportunities and challenges associated with the intangible economy into their policy framework without neglecting or harming those sectors such as natural resources that sustain our economy.

This co-existence is especially important given Canada’s traditional sectors appear to be better at creating jobs and generating exports than the intangibles economy. Even as of 2018, Google’s parent company employed just 99,000 people worldwide17 versus 180,000 at General Motors18 and 2.2 million at Walmart.

The good news is that it is not a binary choice. There is considerable overlap between old and new, traditional and modern, tangible and intangible. Canada’s natural resource sector, for instance, is increasingly drawing on cutting-edge technologies and processes to drive efficiency and reduce its climate emissions. Data, nanotechnology and other innovations are reshaping traditional sectors as much as they are creating new ones.

In fact, it is the modern manifestations of these traditional sectors where Canada may be best poised to become a global innovation leader. It is no accident, for instance, that the Minister of Finance’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth identified agriculture and agri-food and energy and renewables as two of the four domestic sectors with the highest potential to compete and win in the global economy.

This economic dualism requires that policymakers set a north star that recognizes the ongoing importance of traditional sectors and their technology-driven transformations, and the emergence of the new intangibles economy and its unique characteristics and policy peculiarities.

Our north star thus remains sustaining and strengthening Canada’s capacity for competitiveness, innovation and productivity and, in turn, higher living standards, broad-based opportunity and inclusive growth. Progress should ultimately be measured by higher rates of economic growth, rising levels of business investment and new ranks of Canadian-headquartered, globally scaled firms. We have organized our recommendations into three categories that reflect the evolving economic trends and their policy implications, as described in Part One: (1) The Old Classics, (2) The New Intangibles, and (3) Sustainable Humans.

In our view, these are ideas and proposals that ought to enjoy bipartisan support. As former senior advisers to different governments, we have placed a priority on practicality and political survivability. Our recommendations are bold but doable.

Readers may identify gaps in our analysis and prescriptions, including, but hardly limited to, climate change and its economic, environmental and social effects. We have made a conscious attempt to focus our attention on some elements more than others, without meaning to marginalize these other issues’ obvious importance. We simply are trying to concentrate our firepower where debate is under-developed. The road to competitiveness is never-ending and others, no doubt, will lend their voices along the way. We welcome that. Our recommendations are intended to help Canadian governments and other economic actors begin a new and essential phase of the journey.

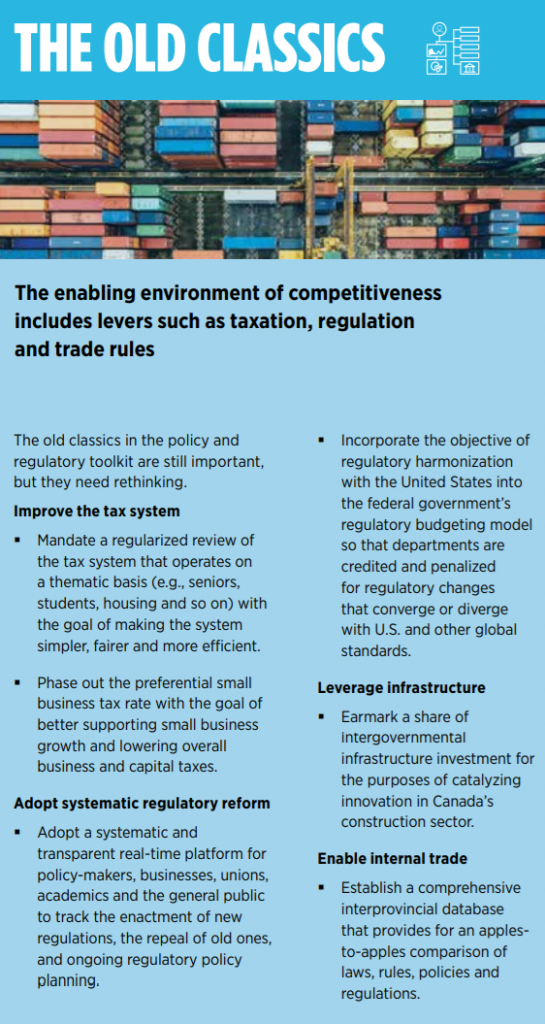

The Old Classics

Foundational frameworks in the era of FAANGs

A private sector cannot soar when public policy or public services act as deadweight. Any pro-competitiveness agenda must consider policies which fall under what the World Economic Forum calls the “enabling environment.” An enabling environment is a jurisdiction’s underlying policy foundations to promote investment, hiring and innovation, including institutions, infrastructure, IT adoption and macroeconomic stability. The quality of these foundational institutions and policies is considered core to a jurisdiction’s economic competitiveness.

Such policy areas as taxation, regulation, public finances, public infrastructure, and trade have stood at the centre of how we thought and talked about competitiveness since the early 1980s. The notion of a competitive “enabling environment” has informed our federal and provincial policy debates about the appropriate role of government within market-driven economies. There are exceptions, of course, such as ongoing government involvement in the dairy and poultry sectors, foreign ownership restrictions in financial services and telecommunications, and sector-based and regional-based subsidies. But Canadian governments from the mid-1980s to the present have generally opted to think about competitiveness and innovation primarily in passive (unshackling the market) rather than active (purposely shaping markets) terms. We have chosen to enable rather than direct.

This impulse has manifested itself in a political consensus in favour of competitive corporate taxation, sound public finances, public investments in education and infrastructure, and a neutral approach to industrial development. Even while targeting public spending on agriculture, aerospace and autos — which are exceptions to the rule — successive governments have generally pursued conventional, liberal investment and trade agendas to enable competitiveness and innovation.

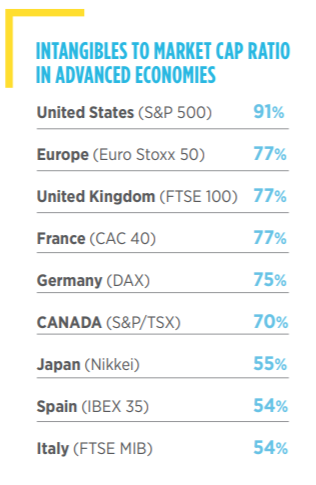

A good example of this passive impulse is the role of indirect subsidies for business research and development compared to direct subsidies. As of 2010, roughly 70% of federal spending related to business R&D came in the form of indirect tax subsidies. The remaining 30% was spread among various direct subsidies such as repayable grants and government-performed R&D expenditures. This balance has since been adjusted due to changes to the Scientific Research and Experimental Development Tax Credit and new direct spending programs such as the Superclusters Initiative. Still, the federal government’s mix of direct and indirect spending on business R&D tilts further towards indirect support than in comparable jurisdictions like Australia, the United Kingdom and the U.S.

Essentially, other than in crisis situations, Canadian governments have taken a laissez-faire approach to the enabling environment when devising a policy agenda in support of competitiveness and innovation. Like other countries, it has ascribed to the political consensus of a conventional, liberal trade and investment agenda.

We call this section “The Old Classics” because, in most cases, these policies are able to weather changing times. The right mix of taxes, sound public finances, as well as predictable legal and regulatory regimes and treaties, are always foundational to macroeconomic success.

Yet the traditional policy framework requires revision given the rise in competitive importance of new intangible areas such as data governance and IP ownership. In this section, we discuss whether and how these economic trends necessitate a refinement of the basic institutions and policies for competitiveness and innovation. We describe the right enabling environment in the era of FAANGs — the tech giants Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google — and their smaller Canadian competitors, and how this environment differs from that of a manufacturing branch economy.

Canada’s enabling performance and the need to resist complacency

Any discussion of Canada’s enabling environment should acknowledge that the consensus described above has served the country well. Though it is far

from perfect and there is certainly room for improvement, Canada provides a strong climate for investment and business development.

The World Economic Forum ranks Canada first among 140 countries for macroeconomic stability and eleventh for our institutions. It has also consistently ranked our financial system as the soundest in the world. And the World Economic Forum is hardly the only source of praise. In recent years, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and others have highlighted the strengths of Canada’s macro-policy framework.

A pro-competitiveness agenda must respond to the new and emerging competitiveness questions of the intangibles economy while continuously reforming and strengthening traditional policy levers that underlie the enabling environment. These ideas are not at odds with each other; policymakers must do both.

Yet there are negative signs, too. Canada has fallen from first in 2011 to sixth in 2019 in the Forbes ranking of business environments,and from seventh in 2011 to twenty-second in 2019 in the World Bank’s ranking. Similar global comparisons and rankings come to mixed conclusions.

The main message from these global rankings and comparative reports is that policy-makers should resist concluding that Canada’s enabling environment requires no adjustment or refinement. Economic competitiveness is a dynamic and relative question. Canada does not have to enact damaging policies for its ranking to fall; other countries just have to enact more competitive ones.

The key takeaway, then, is that a pro-competitiveness agenda must respond to the new and emerging competitiveness questions of the intangibles economy while continuously reforming and strengthening traditional policy levers that underlie the enabling environment. These ideas are not at odds with each other; policy-makers must do both.

Strengthening Canada’s enabling environment

In our consultations, research and analysis, we identified four key areas of reform to strengthen Canada’s enabling environment:

Debates about economic competitiveness tend to focus on the role of taxation, a tendency heightened by corporate tax reform in the U.S. Considerable political attention has since been dedicated to a short-term defensive response to the drop in the overall tax burden on American businesses and investment.

While we have previously discouraged an overemphasis on tax policy as policy-makers think about competitiveness and innovation, neither can it be neglected. A jurisdiction’s tax regime (including its tax mix, rates and structure) is a key determinant of its overall economic competitiveness. It is the reason that both of us supported the previous lowering of the federal corporate tax rate to 15% and the government’s recent, short-term changes to capital expensing. It may also be possible for some provinces to lower their corporate tax rates with minimal revenue loss. But, as we have argued elsewhere, a competitive tax system is a necessary yet insufficient condition for competitiveness, innovation and productivity.

Tax policy changes must take into account fiscal circumstances as well as inherent technical and political challenges. A failure to account for these real considerations risks producing impractical recommendations.

The former observation should be but is not always self-evident. The federal government and several provinces are currently running budgetary deficits. Deficit-financed tax cuts that significantly reduce a government’s revenue capacity risk the kind of structural deficit that bedeviled Canada in the 1970s and 1980s and currently threatens the U.S. in the aftermath of last year’s tax cuts. Canadian policymakers should avoid similar deficits recurring here, especially given the fiscal challenges on the horizon from an aging population and Canada’s reliance on the outside world for investment and trade.

The political controversy over the small business tax reforms in late summer 2017 and the introduction of the GST in 1991 highlight how technical issues and political forces can stymie reform that challenges the status quo. Moreover, as the majority of income tax revenues come from the top 10% of earners, any personal income tax reductions will benefit highincome earners at a time when, for better or worse, most polls show that people want high earners to pay more. This made a tax-cutting agenda during the Harper years susceptible to regular criticisms about harming equity. We each have observed firsthand the challenges of tax policy changes.

Some have argued that the solution to these technical and political challenges is a royal commission on tax reform. The purpose would be to depoliticize tax policy by putting it in the hands of accountants, economists and other technocrats. We are skeptical that this would be useful. Such a process would be slow (UBC economist Kevin Milligan has shown that policy reforms flowing from the Carter Commission in the 1960s came roughly a decade after the launch of the process), and off-loading these sensitive questions to an independent body neglects the extent to which questions about the tax base, structure and rates are shaped by normative considerations. A panel of experts cannot decide how the tax system should be balanced between efficiency and equity, or how it should appropriately treat individuals and families. These judgments are ultimately shaped by competing preferences and political views and belong in the realm of politics.

Instead, policy-makers should focus on incremental yet constructive reform. A mandated and regularized review process that evaluates and reforms different components of the tax system annually would, in our view, be more likely to survive the bureaucratic and political process and move the ball down field. The current government’s consolidation, refinement and enhancement of tax expenditures related to caregiving is a good example. This 2018 reform made the tax system simpler, more efficient and more progressive at a minimal incremental cost.

This thematic approach could be expanded to include home ownership, post-secondary education, employment, medical expenses, savings and retirement, and aging, as well as fossil fuels, clean energy investments, capital expensing and small businesses. Moving through the tax system on an incremental and thematic basis may not produce fundamental change but the resulting reforms could simplify the system, make it more efficient and make it more progressive. And the resulting reforms would become baked into the system, yielding big improvements over time. As part of this exercise, policy-makers could consider the mix of taxes on income, capital and consumption, and if and where this mix should be adjusted for efficiency and other policy objectives.

In our consultations, we frequently heard ambitious calls for the elimination of the preferential rate for small businesses. There is evidence that the lower rate for small businesses, which fell to 9% this year, creates the equivalent of a “welfare wall” for small businesses. A higher tax rate above the $500,000 income threshold can discourage firm growth or encourage tax planning just as the wrong mix of welfare benefits and minimum wage can discourage people from seeking employment.

Policy should help Canada’s small businesses grow and, in turn, make them more likely to invest in and to export technology. It should not encourage stasis. Phasing out the preferential rate would remove this distortion from the tax system and produce considerable new revenues (possibly as much as $6 billion per year) that could be used to lower the general corporate tax rate on a revenue-neutral basis.

This is a good idea with considerable political risks. Nearly 745,000 firms benefit from the current tax treatment. Phasing it out without (or even with) offering other benefits could produce a political maelstrom that would make the response to 2017’s more technical changes seem modest. Incorporating such a change in a broader tax package that lowers the general corporate tax rate, and possibly changes personal income tax rates, might provide a chance of success.

Regulatory reform requires greater ambition and rigour. Policy-makers regularly talk about “red tape reduction” as a priority and there has been progress on simplifying or repealing outdated and onerous regulations at the federal level and in various provinces. But these exercises have generally involved “weed whacking” rather than systematic reform.

Moreover, political pronouncements about red tape have often occurred against the backdrop of the creation of new rules, regulations and other impediments to investment. Canada’s poor performance in international comparisons of regulatory policy is evidence of this. According to the OECD, Canada now ranks 34th of 35 countries for the time it takes to get a general construction permit. The World Bank observes that it takes an average of 250 days to receive a general construction permit in Canada, the longest amount of time in the G7 and almost three times as long as in the U.S. The World Economic Forum ranks Canada 38th of 137 countries on the burden of government regulation. And there is plenty of evidence that Canada underperforms comparable jurisdictions in the regulation of natural resource projects. For instance, oil well licensing in Alberta is much slower compared to Texas.

In our consultations, global energy companies told us that Canada’s regulatory requirements lead to significantly longer lead times between discovery and development, hindering their efforts when seeking investment capital from international headquarters. Canada’s world-class mining and pipeline companies are moving investment and head office jobs outside Canada. Some smaller organizations said that they lack the capacity to keep up with the flow of regulatory additions and changes. We were told by innovative sectors — from cars to canola — that regulators cannot keep pace with technological advances. And legacy companies regularly lamented that their upstart, often external, competitors, whether fintech and banking or digital services and global platform companies like Facebook and Google, were able to play by different regulatory and tax rules.

Most foreboding, in a recent annual survey, nearly three-quarters of Alberta-based energy executives cited regulatory compliance as a deterrent to investment in the province; only 10% of executives in Texas and 7% in Kansas raised the same concern.

I t is a positive sign that the current government’s Fall Economic Statement committed to regulatory reform including yearly deregulation bills and the creation of the new Centre for Regulatory Innovation.51 Smart, effective and competitive regulation needs to become the subject of a political consensus in Canada. And a way to hold government’s feet to the fire must be found if steady progress is to be made.

The government should adopt a systematic approach to understand the origins of regulations, how they interact with other federal and provincial rules, how they compare with those in peer jurisdictions, and what are the metrics for measuring their benefits and costs. As with our earlier step-by-step tax reform proposal, better functioning and transparent process of continuous review and modernization is required to achieve the objective of better functioning regulatory system. Sometimes this may mean new or reformed regulations, sometimes greater speed in adjusting regulations to new technological and market developments, and often it will require clearing away redundant regulations. In all cases, it should mean greater certainty and clarity over who regulates what. Subjecting businesses to both federal and provincial regulations creates confusion and slows movement without adding to the public interest.

Canada needs a mechanism that provides real-time public tracking on regulations that impact on global competitiveness so that businesses, labour unions, NGOs, academics, think-tank scholars and other levels of government can monitor progress and hold governments accountable. Right now, the system lacks communications and coherence. From our experience, it is not uncommon for departments to unknowingly seek Cabinet approval for new regulations based on statutes that have been repealed. Regulatory duplication across departments and with other levels of government is examined on an ad hoc basis. This inability to comprehensively analyze regulatory policy is a major impediment to meaningful reform.

There is no reason that Canada cannot become a global leader in innovative public infrastructure and support a dynamic, forwardlooking construction industry that can compete for major projects around the world.

Arizona and Kentucky have recently contracted with a U.S.-based software company to build an interactive database to track cost and benefit considerations across their regulatory agencies.52 Canadian governments should consider a similar model to create a centralized, standardized and interactive regulatory database.

Another step is to pursue greater regulatory harmonization with our major trading partners, including the U.S. This should apply to the regulation of goods and services in the economy and to project approvals, permitting and licensing. Unjustified regulatory differences and their resulting costs amount to an inefficiency tax on Canadian firms and investors.53 This indirect tax imposes undue costs on bilateral trade and provides an advantage to U.S. states competing for investment with Canadian provinces and territories. New efforts, such as establishing global standards for issuing permits that provide for best practices and transparent mechanisms to compare different jurisdictions, can nudge countries to improve their policy frameworks. This agenda is not about a blind following in the direction of de-regulation, but when Canadian policymakers design regulatory policies that deviate from global competitors, there should be an onus to justify the economic and public interest case.

It is promising that the current government has signed a renewed Memorandum of Understanding with the U.S. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs to advance the regulatory co-operation file. The 2019 budget provided incremental resources to the Treasury Board Secretariat to begin translating the agreement into an actionable agenda.

A creative option would be to incorporate the goal of regulatory harmonization in Ottawa’s regulatory budgeting legislation (the “one-for-one” rule) so that departments could be credited or penalized for enacting new regulations and regulatory reforms that converge or diverge with U.S. standards and practices.55 This approach would tilt bureaucratic and political incentives in the direction of greater regulatory harmonization.

High-quality public infrastructure can be a source of economic competitiveness. Yet Canada underperforms in this area. Canada has seen its ranking on the overall quality of its infrastructure fall from 15th in 2012 to 23rd this year according to the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness analysis.

The good news is that the federal government and several provinces have committed unprecedented funding for public infrastructure. The bad news is that we continue to face challenges in prioritizing productivity enhancing projects such as public transit, leveraging private capital and expertise, and managing intergovernmental decision-making in a time-efficient way. We must make these issues a priority if Canada is to take full advantage of the funding pledged by Ottawa and the provinces and territories.

The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) was conceived to leverage private capital and project management expertise in order to advance the current government’s ambitious plan for infrastructure investment. The bank was seeded with $35 billion and given a mandate to draw in private and institutional capital to build revenue-generating infrastructure. The early signs have not been positive. Starting this new organization has been consumed by the usual bureaucratic delays. Few infrastructure projects have been tapped.

We should not flinch, however. Canada’s pension funds are some of the most sophisticated institutional investors and are heavily invested in infrastructure around the world. The bank can play a useful role in catalyzing their investments here in Canada.

As part of a north star for Canadian competitiveness, policy-makers should apply a “competitiveness filter” to project prioritization and selection. There is a balance to be struck between federal leadership and local priority setting, but the CIB can start by prioritizing new and dynamic infrastructure projects. This might include a special focus on such areas as

climate adaptation, export infrastructure, smart cities and getting ahead of the requirements to be early adopters of the Internet of Things, which enables technologies from autonomous vehicles to heating and cooling systems to interact continuously with grids. PPF has previously asked whether the next dollar of infrastructure money is better spent on asphalt or transponders. A long-term competitiveness filter is critical to answering such a question.

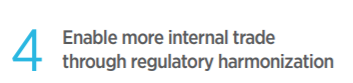

Liberalizing internal trade is building political momentum. This is the good news. The bad news is that Canada is still at this obvious starting point. Strategic competitiveness policies assume that before firms become exporters, they need to sharpen their skills domestically. Dividing an already small and dispersed national market hobbles the ability for global champions to grow from a Canadian base. Obstructed at home, too many Canadian companies reluctantly turn to the more hospitable U.S. market to build their base.

Interprovincial trade barriers in the form of provincial or local preferences, regulatory differences or legislated prohibitions impose economic costs beyond stifling business development. Estimates of these costs vary considerably. A 2008 report by the Government of Alberta estimated the cost to Canada’s economy to be $14 billion per year. A 2016 Senate committee put the number as high as $130 billion per year. Other figures fall somewhere in between.

Interprovincial trade barriers essentially function like tariffs. In fact, Statistics Canada estimates that they are the equivalent of a 6.9% tariff on trade within Canada. It is notable that Canadians (rightly) protested President Trump’s imposition of tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum products but ignore the significant tariffs that our own governments impose on Canadian goods and services. It is perverse and self-defeating.

As a measure that promotes higher levels of economic growth, an assault on these interprovincial “tariffs” should be low-hanging fruit. The Bank of Canada has estimated that removing interprovincial trade barriers could add 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points to potential annual output. A recent Bank of Montreal study concludes “the positive impact from free interprovincial trade would cumulate over a decade to add as much as 2% to national GDP, or nearly $50 billion.” That is more than twice Canada’s exports to China, its second-largest trading partner.

The Canada Free Trade Agreement, which came into force on July 1, 2017, is still a work in progress. While the ambition and rhetoric are high, the results have been limited. The most promising aspect of the agreement is the establishment of the Regulatory Reconciliation and Co-operation Table, with a mandate to reconcile regulatory differences among the provinces. But the federal government operates at a disadvantage; it does not erect these barriers nor can it unilaterally dismantle them. We are told that Nova Scotia has begun unilaterally lowering internal barriers. Alberta’s United Conservative Party has made a similar commitment. This kind of behaviour should be encouraged.

Reducing interprovincial trade barriers is hard work. Most are subtle and unjustified regulatory differences that cannot be resolved through mutual recognition. There is no big-bang solution. They can only be eliminated by moving to a common standard. For instance, Alberta’s labour code protects workers who require Reservist leave after 26 weeks of consecutive employment, while Saskatchewan’s only requires 13 weeks of employment. Why is this different? What is the point? And, most importantly, which standard should be adopted? Any common standard is better than different ones.

Identifying these differences and answering these questions is painstaking yet important work. The main challenge is that many of the provinces do not use the same language, legal design and structure so it is laborious to figure out where regulatory differences exist. The federal government could support a methodical exercise by funding the creation of a comprehensive inter-provincial database that provides for an apples-to-apples comparison of laws, rules and regulations across the provinces and territories. It could operate similarly to the 25-year-old health database run by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, which has a multiple jurisdiction governance structure. This would support the work of the Regulatory Reconciliation and Co-operation Table and the provinces to expedite the process of reconciling unjustified regulatory differences and provide data to validating those jurisdictions moving in the right direction.

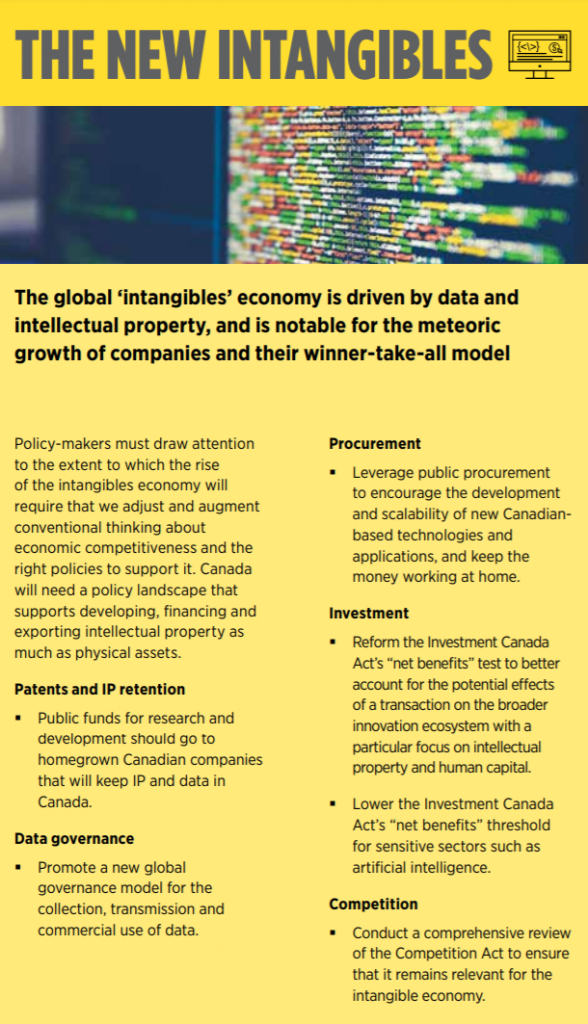

The New Intangibles

How does Canada win in a data-driven economy, where value is in intangibles?

The foundational drivers of competitiveness are necessary yet insufficient for the new intangibles economy. Policy-makers must go beyond them and address the new drivers of competitiveness.

Canada is accustomed to thinking about competitiveness and productivity in a 20th century mindset, where textbook economics says that the two most important variables of factors of production are labour and capital. Similarly, a 20th century company balance sheet focuses on the tangible, physical things used to generate revenue for a company — including both fixed assets, such as machinery, buildings and land, and current assets, such as inventory. This is the labour-intensive, factory-based model of automotive manufacturers, General Electric and the energy industry.

The 21st century data-driven economy changes this. It will have increasingly less to do with tangible assets, and more to do with intangible assets, such as IP, data and copyrights. It does not effectively replace labour and capital as drivers of economic growth per se. But it redefines how to conceptualize various economic inputs and their relative role in driving economic growth. At a minimum, it forces us to make a clear distinction between the tangible and intangible economy — a discussion that has hardly penetrated the policy-making community thus far.

Over the last decade, technology has brought down the labour share of GDP across OECD countries, including Canada, where it fell in 1990 to just over 50% in 2015. This trend has generally been interpreted as a symptom of suppressed wage growth driven by a combination of corporate concentration, technology and various other labour market factors. Artificial intelligence, quantum computing and their applications will further dramatically disrupt our labour markets — and wages — in the future. The result will be even greater labour bifurcation and income inequality.

More generally, if intangibles are the main driver of the emerging data-driven economy, then it follows that to remain competitive as a country, Canada must rethink how to facilitate innovation and enable ecosystems that drive innovation and build greater capacity in the intangibles economy. This has considerable implications for public policy.

Most of the current ecosystem of economic enablers for an innovative economy — such as free trade, competitive taxation, innovation programs based on demand, physical infrastructure, and smart regulations — exist to help Canada perform reasonably well in a world of tangible assets. But they are not necessarily set out for intangibles. Put differently: a classic enabling environment will only get us so far in the new economy. It is necessary yet not sufficient, and so it is essential to build on it with new thinking and new policies. Indeed, we believe a new set of policies are needed to help Canada thrive in a world where intangibles (including data) will increasingly become the primary source of economic competitiveness and a major creator of economic wealth.

The analogy is often made that data is the new oil. While a handy metaphor in terms of their foundational roles in their respective economies, petroleum is found in the ground and can only be transported over land and water controlled by one sovereign state or another.

Data is intangible and, as such, harder to subject to the same liberal-based market rules. Therefore, a regimen of competitive-enhancing policies will not be easy to enact in this new economy and will probably require international co-operation among like-minded countries, usually those that Facebook, Amazon, Google and Alibaba are just visiting. With so much at stake, it is imperative to hold a major debate about technology and competitiveness.

While Canada has enjoyed great economic success in the past, historically it has not been a topperforming country when it comes to innovation. Canada has exhibited a spate of bad habits and outdated thinking when it comes to adapting to big structural shifts in the global economy; it has always been simpler to rely on our abundance of natural resources for wealth creation and our close relation to the U.S. in adopting new innovations. As demonstrated at the time of the demise of Nortel Networks, Canada has not been attentive to the value of IP as a driver of competitive advantage, even when it has been wholly or partly funded by public dollars.

Policy-makers must become more attuned to the trends of an intangibles economy and, in turn, the extent to which it requires us to adjust, refine and improve our competitiveness-related policies. The first order of business is to understand what is happening.

We mentioned earlier that we sought to obtain a Canadian comparator for the data on the share of S&P 500’s value represented by intangible assets. The S&P 500’s share has climbed from 16% in 1976 to 91% today. We discovered that few, if any, had carried out such analysis of the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX). RBC Economics was kind enough to crunch the numbers for us based on Bloomberg’s price to tangible book value per share.